As most readers are no doubt aware by now, Jonathan Demme has died. Taken from us aged 73 from a reported combination of heart disease and cancer, the director, writer, producer and documentarian leaves behind a remarkably varied and illustrious body of work. As can often be the case on these occasions, I come to the sad realisation that I’m really not as familiar with the length and breadth of that oeuvre as I should be. Beyond Caged Heat (whose praises I sang here several years ago), I haven’t seen any of Demme’s earliest films, and while I did see Something Wild and Married to the Mob, both were so long ago they’re hazy in my memory.

As most readers are no doubt aware by now, Jonathan Demme has died. Taken from us aged 73 from a reported combination of heart disease and cancer, the director, writer, producer and documentarian leaves behind a remarkably varied and illustrious body of work. As can often be the case on these occasions, I come to the sad realisation that I’m really not as familiar with the length and breadth of that oeuvre as I should be. Beyond Caged Heat (whose praises I sang here several years ago), I haven’t seen any of Demme’s earliest films, and while I did see Something Wild and Married to the Mob, both were so long ago they’re hazy in my memory.

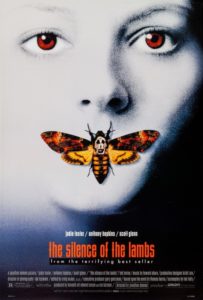

However, as a lifelong horror fan, the one Demme movie which will always be close to my heart is naturally his Oscar-laden 1991 classic The Silence of the Lambs. And yes, let’s make this abundantly clear straight away: whatever anyone says, of course The Silence of the Lambs is a horror movie, and any denial of this is absurd and rooted in anti-genre snobbery. That said, to play devil’s advocate, it’s understandable that some would declare it to be (wince) somehow ‘more’ than horror, as it was a film that pushed the genre to new heights of sophistication which few can really be said to have reached since; and God knows they tried, as its echoes can be felt in so much of the horror fare to have come in its wake.

Thinking about it, though, from a certain point of view The Silence of the Lambs may have hurt the horror genre more than it helped, in the short term at least. When a film proves a massive hit both commercially and critically, sweeping the board at the Oscars in the process (lest we forget, along with It Happened One Night and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, it’s one of only three movies to pick up all the big five Academy Awards: film, director, actor, actress, screenplay), you’d be forgiven for assuming that would mark a new golden age for its genre. Yet as most horror fans will surely agree, the 1990s was one of the worst decades ever for horror. Some great films were made, no question about that, but the bad outweighed the good by a significant margin, and the genre fell out of favour with the mainstream, largely banishing it from the big screen and condemning it to the direct-to-video market (not that there aren’t still some gems to be found in that arena).

Thinking about it, though, from a certain point of view The Silence of the Lambs may have hurt the horror genre more than it helped, in the short term at least. When a film proves a massive hit both commercially and critically, sweeping the board at the Oscars in the process (lest we forget, along with It Happened One Night and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, it’s one of only three movies to pick up all the big five Academy Awards: film, director, actor, actress, screenplay), you’d be forgiven for assuming that would mark a new golden age for its genre. Yet as most horror fans will surely agree, the 1990s was one of the worst decades ever for horror. Some great films were made, no question about that, but the bad outweighed the good by a significant margin, and the genre fell out of favour with the mainstream, largely banishing it from the big screen and condemning it to the direct-to-video market (not that there aren’t still some gems to be found in that arena).

Perhaps it’s unfair to hold The Silence of the Lambs directly responsible for all this in itself; but the fact that its status as a horror film was so flagrantly overlooked in its critical appraisals, and arguably in much of its promotion, lent weight to the general disdain with which horror as a label was treated by the mainstream, and generally is to this day. ‘Psychological thriller,’ instead, became the preferred term, and Demme’s film spawned a slew of imitators presenting homicidal maniacs at work, but with a pointed emphasis on the police investigation rather than the victims because heaven forbid they wind up looking like slashers. We had the likes of Single White Female, The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, Copycat – and ultimately, David Fincher’s Seven, which proved almost as significant a game changer as Silence of the Lambs had been. Yet all the while, the H-word was seemingly forbidden.

SPOILERS beyond this point – but come on now, if you haven’t seen The Silence of the Lambs, what the hell have you been doing with your life?

Remember what Hannibal Lecter tells us. “Of each particular thing ask: what is it in itself? What is its nature?” Now really, this is a film about a serial killer who abducts women, holds them captive at the bottom of a dank hole in his dungeon-like basement, and cuts off their skin, in which the only person with a clue to the killer’s identity is himself a psychotic cannibal. If you want to say that isn’t the premise of a horror movie; well, you keep telling yourself that, love.

I suppose the key thing is, Demme – like Friedkin and Kubrick before him – didn’t set out to make a horror movie, but the horror movie. From pretty much beginning to end, the director strives to put us directly into this terrifying world and make us feel the fear of the protagonists – and pivotal to this, of course, is Jodie Foster’s Clarice Starling. As has long since been widely acknowledged, The Silence of the Lambs is a very much a feminist horror movie, and Demme’s directorial style throughout has often been read as a critique of the ‘male gaze’ of cinema, thanks to the way that almost every scene with Starling puts us directly into her shoes, with Foster’s co-stars staring straight into the camera. This is a huge part of what gives the film such a disquieting intimacy, and heavily promotes the audience’s identification with Starling; which, as Carol Clover famously asserted, is the principal role of the horror movie’s final girl, an archetype which Starling very much fits into even if she isn’t a screaming babysitter or camp counsellor. On top of which, Demme’s emphasis on point-of-view shots can easily be considered an early benchmark for the found footage approach which would come to prominence at the tail end of the decade with The Blair Witch Project, most pointedly in the final confrontation with Ted Levine’s Buffalo Bill, shot from the killer’s perspective. Substitute Bill’s infra-red goggles for a camcorder on night vision mode, and you’ve got the template for every POV shocker we’ve seen since.

I suppose the key thing is, Demme – like Friedkin and Kubrick before him – didn’t set out to make a horror movie, but the horror movie. From pretty much beginning to end, the director strives to put us directly into this terrifying world and make us feel the fear of the protagonists – and pivotal to this, of course, is Jodie Foster’s Clarice Starling. As has long since been widely acknowledged, The Silence of the Lambs is a very much a feminist horror movie, and Demme’s directorial style throughout has often been read as a critique of the ‘male gaze’ of cinema, thanks to the way that almost every scene with Starling puts us directly into her shoes, with Foster’s co-stars staring straight into the camera. This is a huge part of what gives the film such a disquieting intimacy, and heavily promotes the audience’s identification with Starling; which, as Carol Clover famously asserted, is the principal role of the horror movie’s final girl, an archetype which Starling very much fits into even if she isn’t a screaming babysitter or camp counsellor. On top of which, Demme’s emphasis on point-of-view shots can easily be considered an early benchmark for the found footage approach which would come to prominence at the tail end of the decade with The Blair Witch Project, most pointedly in the final confrontation with Ted Levine’s Buffalo Bill, shot from the killer’s perspective. Substitute Bill’s infra-red goggles for a camcorder on night vision mode, and you’ve got the template for every POV shocker we’ve seen since.

Equally influential was the film’s presentation of murder; and this, again, is perhaps where The Silence of the Lambs stood apart from the dominant horror formats of the time, coming in the wake of the splatter-happy 1980s in which the name of the game was to show every impact wound in eye-opening full colour. By contrast, here only one death is presented on screen – Bill’s, at the end – and, beyond Lecter’s face-biting jail break, there isn’t much in the way of on-screen violence either. Demme instead focuses on the aftermath of violence: pathologist photos, bodies on the autopsy table, bloodied fingernails broken off in the wall of Bill’s pit of despair. Note how, when Chilton sadistically shows Starling the photograph of the nurse attacked by Lecter, we’re shown only her reaction under the harsh red light whilst regaled with Chilton’s unnervingly enthusiastic account of what occurred. It’s this emphasis on description which really gets under the viewer’s skin; and this, in a way, might also be seen as a precursor for the Lewtonesque approach that M Night Shyamalan and the J-horror wave would take before the decade was out, hinging on the conceit that what is imagined is invariably more terrifying than what is directly shown.

That having been said, Demme doesn’t shy away from showing us truly horrific sights here and there. The skinned and disembowelled corpses may not linger too long on the screen, but they linger hard in the memory, and there’s clearly grounds to consider The Silence of the Lambs to be an early harbinger of the ordeal horror wave of the 2000s (or ‘torture porn,’ if we must call it that). 1995’s Seven took us a little further down that path, again showing very little in the way of acts of violence but emphasising the horrendous aftermath, Andrew Kevin Walker’s script having dreamed up all manner of hideous ways to die. By the end of the decade, on the other side of the Pacific, Takashi Miike’s Audition finally took us right over the edge with its eye-popping displays of torture, and from there it was a hop, skip and a jump to the Saw and Hostel movies. Yes, all these films harked back to the shockers of the 70s – Last House, Chain Saw, I Spit on Your Grave and the like – but from a contemporary perspective, the hideous exploits of Buffalo Bill and Hannibal Lecter may very well be regarded the first steps on that ladder toward mass misery and mutilation in the multiplexes. And surely there’s no denying that Hannibal’s penchant for verbose monologues set the stage for John Doe and ultimately Jigsaw.

That having been said, Demme doesn’t shy away from showing us truly horrific sights here and there. The skinned and disembowelled corpses may not linger too long on the screen, but they linger hard in the memory, and there’s clearly grounds to consider The Silence of the Lambs to be an early harbinger of the ordeal horror wave of the 2000s (or ‘torture porn,’ if we must call it that). 1995’s Seven took us a little further down that path, again showing very little in the way of acts of violence but emphasising the horrendous aftermath, Andrew Kevin Walker’s script having dreamed up all manner of hideous ways to die. By the end of the decade, on the other side of the Pacific, Takashi Miike’s Audition finally took us right over the edge with its eye-popping displays of torture, and from there it was a hop, skip and a jump to the Saw and Hostel movies. Yes, all these films harked back to the shockers of the 70s – Last House, Chain Saw, I Spit on Your Grave and the like – but from a contemporary perspective, the hideous exploits of Buffalo Bill and Hannibal Lecter may very well be regarded the first steps on that ladder toward mass misery and mutilation in the multiplexes. And surely there’s no denying that Hannibal’s penchant for verbose monologues set the stage for John Doe and ultimately Jigsaw.

Of course, whilst there’s little question that much of the horror which came in the wake of The Silence of the Lambs failed to measure up, I should hope most will agree that the follow-up movies Hannibal and Red Dragon were a major let-down. Hopkins has expressed regret over playing Lecter again; really, the writing was on the wall as soon as both Foster and Demme declined to return. (Side note: I never even bothered seeing prequel Hannibal Rising. Nor have I ever seen the Hannibal TV series, although I’m reliably informed that’s excellent.) We might also note that Demme never made another horror film; and in some respects, who could blame him? If you can revitalise and redefine a genre with a single film, there’s something to be said for never looking back.

Again, The Silence of the Lambs is but one of the many contributions Demme made to cinema, and I expect I’m not alone in saying I intend to familiarise myself with the rest of his filmography; but really, this was always the film he was going to be remembered for. And quite rightly so, as it’s a true masterpiece which is every bit as compelling, engrossing and unnerving today as it was 26 years ago. Let us raise a glass of nice Chianti and toast the memory of the director who made it so.