By the time Stagefright emerged in 1987, the Italian exploitation film scene that had managed to outlast most of its European counterparts was on its last legs. Within a few years, the slew of horror, action and sex films that had been churned out since the 1960s was reduced to a trickle, and then more or less ground to a halt. The home video boom that had helped make Italian cult cinema so popular also killed off the international market for new titles. While movies were still being made, few of them were memorable and only a handful have achieved the lasting popularity of their predecessors from just a few years earlier.

Stagefright is one of the few. Director Michele Soavi was seen as the great hope for a new generation of Italian horror directors, though in the end, his career was brief and – with the exception of the critically acclaimed Dellamorte Dellamore – fairly undistinguished. However, Stagefright suggested a potential new talent emerging. It’s not that the film is particularly original, but Soavi brings a definite visual flourish to the rather basic story.

Often seen as a late-era Giallo film, Stagefright is actually closer in style to American slasher movies of the 1980s, replacing the black-gloved killer and whodunnit approach of the Giallo with the established idea of the masked maniac, here an escapee from an asylum who is terrorising a group of young people. However, the film offers its own twist on the concept.

The film opens deceptively – viewers might groan, expecting the worst, as a cliched looking 1980s hooker walks down a stagey looking street and is attacked by a maniac who is, bizarrely, wearing an owl head mask. As people run to see what is happening, things get odd. Is the killer dancing? The camera pulls back to reveal that this is, in fact, a theatrical performance, the rehearsal for a genuinely dreadful-looking (and so impressively authentic) dance musical that just isn’t coming together. Director Peter (David Brandon) is a dictator who has ego and ambition but no talent, and his cast of hapless nobodies in search of their big break seems equally lacking in ability. When leading lady Alicia (Barbara Cupisti) hurts her ankle, wardrobe lady Betty (Ulrike Schwerk) breaks the director’s rules by leaving the building and taking her to a hospital. OK, so it’s a psychiatric hospital, but they still have doctors, right?

This somewhat laughable contrivance allows psycho killer (and former actor) Irving Wallace to escape and hide in their car, travelling back to the theatre with them and then killing Betty as Alicia goes inside to face her director’s wrath. As the police arrive to investigate the crime, Peter has a cunning idea – if they change the unnamed killer in their play to Irving Wallace, they can cash in on the murder (he tells the press that Betty was an actress in the play) and attract massive crowds. He locks the doors of the theatre and prepares to rehearse his cast all night. What could possibly go wrong?

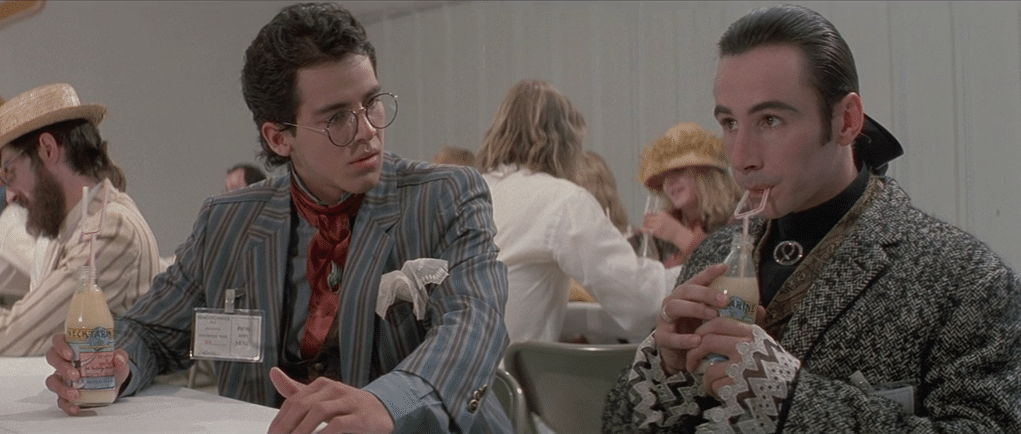

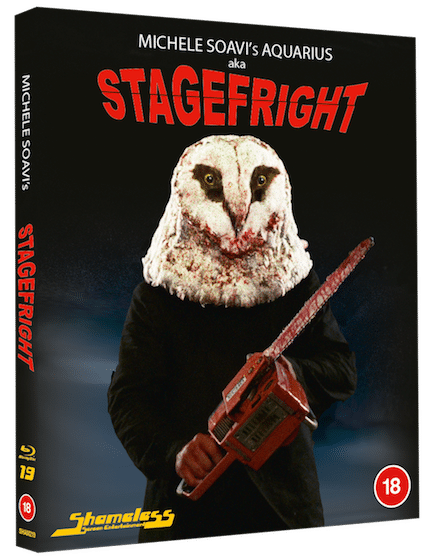

Of course, the real killer has slipped inside too and is soon offing the performers using the sort of handy tools you often find backstage in theatres – axes, power drills, chainsaws and so on are put to use in a frantic second act where the deaths come thick and fast. Soavi delivers these murders with a sense of grandeur and plenty of gore, showing the influence of Dario Argento in his extravagant setups and a touch of Lucio Fulci in his use of graphic violence. The killer – for no good reason, when you think about it – has donned the owl mask previously worn in the stage show by the ultra-camp Brett (Giovanni Lombardo Radice, here performing under his John Morghen pseudonym), and once he’s killed everyone except the Final Girl Alicia, the film takes an odd turn. As she desperately tries to find the keys, the killer positions the corpses on stage in a grotesque tableau and then plays baseball with the severed heads! It’s a weird moment, and definitely eerie in a strange way, the masked murderer sitting in a chair waiting, feathers flying in the air, dead bodies surrounding him. It briefly suggests that the film might have more ideas going on than the average slasher, but it eventually gets back on track and ends in classic slasher style, complete with an unstoppable killer who is never quite dead.

Soavi certainly gives his film a visual polish that is missing from many a slasher movie, and it is this that perhaps most closely ties it to the Italian Giallo thriller tradition. He certainly wears his influences on his sleeve, and that’s no bad thing visually. Luckily, he also manages to keep the story moving along, and the screenplay by Anthropophagous himself George Eastman, while chock full of cliches, wastes no time and keeps the action centred within the theatre (we get occasional cuts to a pair of useless cops – one of whom is Soavi – parked outside the theatre, but this isn’t damaging in the way that, say, the sudden cut to exterior action in Demons is). Soavi certainly knows how to get the best out his basic story, and brings a Grand Guignol sense of the grotesque to the action with a series of grisly, if not especially inventive killings. Simon Boswell’s score is interesting – at best, it is a neat variation on the electronic rock of Fabio Frizzi and Goblin, at worst, it is ultra cheesy, though this is presumably deliberate, as it is supposed to be the soundtrack music of the equally cheesy stage show being rehearsed.

Stagefright is far from perfect, of course. The acting is variable, the dialogue terrible and there are several moments that are likely to induce unsolicited laughter. There’s no escaping the fact that the owl mask is ludicrous, though once you get used to it, it becomes more effective. And it’s certainly an exercise in style over substance, all effort doing into making the film look great rather than hold together as a story. But it holds up rather better than you might expect for a film so wedded to Eighties imagery. It might ultimately be little more than fluff, but it’s entertaining fluff.

Stagefright (1987) gets a fresh release from Shameless Films on December 27th 2021.