On occasion, you see a film – whether a short film or a feature – and something about it stays with you afterwards. Something about the visuals, perhaps, or some ingenious touch to the plot, or its characters – or perhaps some of its hints of a universe existing on its periphery, not fully extrapolated, but intact and understood nonetheless. As such, I’ve been pondering some of the finer details of short film The Wyrm of Bwlch Pen Barras a lot since seeing and reviewing the film a few weeks ago; I’d go so far as to say that it meets all of the criteria above, and has successfully got under my skin. Keen to find out more, I was very happy to speak to the director and writer of Wyrm, Craig Williams, who kindly agreed to answer some of my questions.

Many thanks to Craig and the team for taking the time to speak to Warped Perspective. Much appreciated!

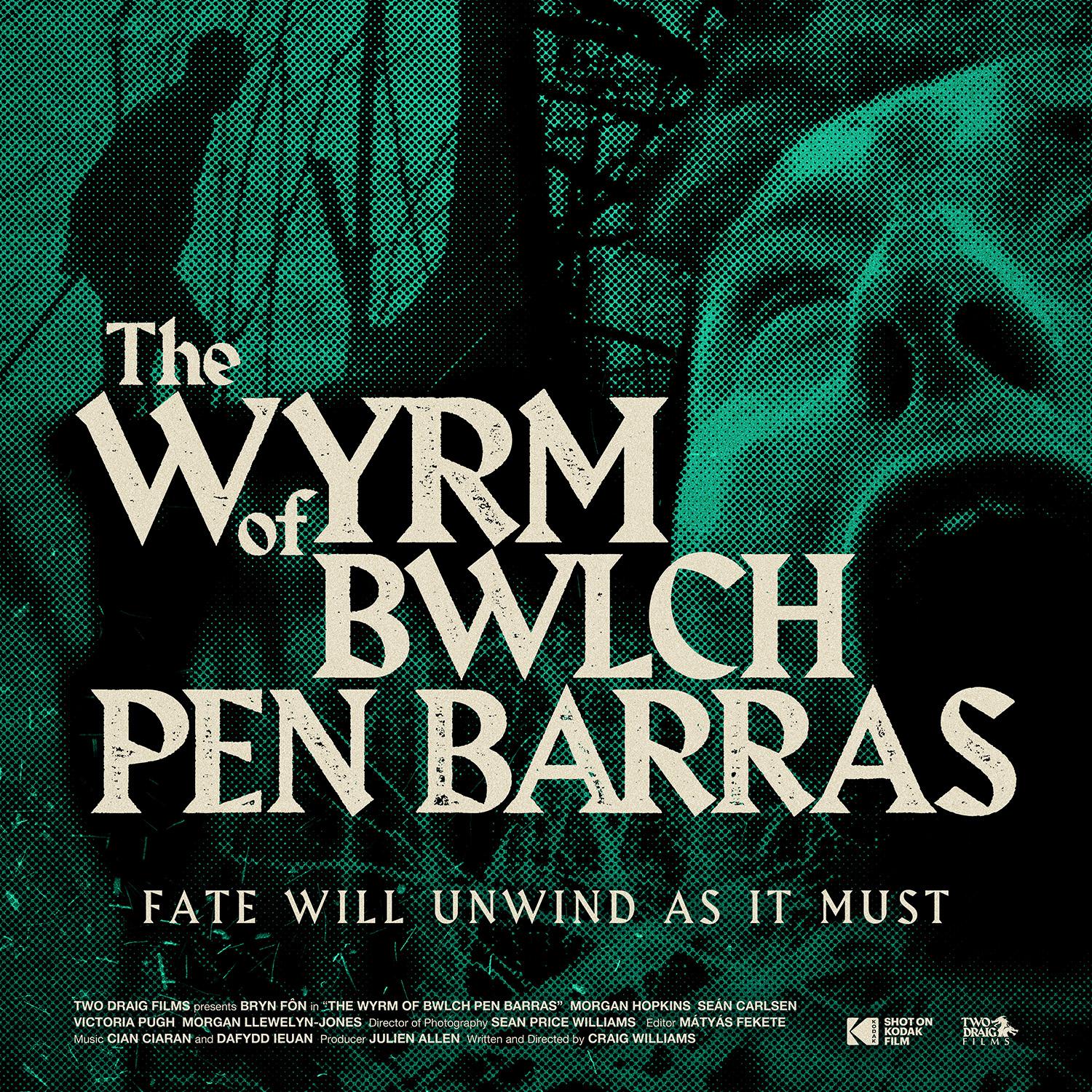

Warped Perspective/Keri: My first question is actually about your striking opening credits: they look reminiscent of other, older folk horror films (though of course that impression dissipates as soon as the characters in the film start using modern tech, like mobile phones, which has a great destabilising impact for the audience). Was getting the right tone on those opening credits important to you? And I have to ask – did any particular films inspire them?

Craig Williams: I absolutely love the genre films of the 70s; the kind of films the great film writer Michael Weldon would class as psychotronic. The work of Jess Franco, Dario Argento, Jean Rollin, etc. – that’s my aesthetic ideal. But I wanted to channel the spirit of that era in a modern genre film by juxtaposing Hammer-style credits, familiar folk horror reference points and an arcane-sounding title with a more grounded, quotidian vision of the present day in rural Wales (eg: the mobile phone, new model Range Rover and also the cable ties on Dafydd as he is marched up the hill).

The titles were designed by the artist Richard Wells, who has worked on so many films and TV programmes that I love, including Doctor Who, In the Earth and several of Mark Gatiss’s shows. I’ve been a huge fan of his work for years, so I knew from the outset that I wanted to ask him to design the posters and titles for Wyrm, and we were so thrilled that he agreed to do it. I know it’s a bit of an indulgence to have the titles appear at the beginning of a short film, but I hope they help set the tone. Given that nothing supernatural happens for the first fifteen minutes of the film, I still wanted to give a clear indication of where it was going, genre and influence-wise, and I think the titles are instrumental in that.

WP: Your film is presented in Welsh language. Whilst there have been more and more genre titles emerging over the past ten years which use Welsh, such as – quite recently – The Feast/Gwledd (2021) – was this in any way a difficult decision for you or the team? Or was using the Welsh language always the plan for The Wyrm of Bwlch Pen Barras?

CW: With Gwledd, Lee Havan-Jones has shown that Welsh-language horror can succeed on the international stage. I think we’ll start to see the impact of that playing out over the next few years. He’s done an amazing thing.

The Wyrm of Bwlch Pen Barras was originally written in English with some scenes in Welsh. The night before we were due to shoot, one of the actors asked whether I was open to shooting English and Welsh versions of the film side-by-side which, thanks to the pioneering work of Ed Thomas and Ffion Williams at Fiction Factory, has become more common with high-profile Welsh television shows. Julien Allen (my producer and creative partner on the film) and I had considered this approach from the beginning, but we were worried it was too much to ask of everyone, especially with such a tight shooting schedule. But the cast and crew were enthused by the idea and so encouraging, so that’s what we ended up doing.

We have therefore cut two completed versions of the film, one in English (with some Welsh at the end) and one purely in Welsh (with only a line from Dai in English). But it soon became evident to us during the post process that the Welsh version felt richer and more true to the material, so that’s the one we ended up submitting to festivals. I am so pleased we took this approach – Welsh is my first language, so this version of the film also feels more personal and meaningful to me.

WP: I think I’m right in saying that another working title for the film was Arswyd Bwlch Pen Barras (which I also think I’m right in saying translates to The Horror of Bwlch Pen Barras) – so if I do have that correct, and pardon my almost negligible Welsh if I’m wrong, what drove the title change to invoke something quite specific from British folklore, the idea of a ‘wyrm’?

CW: We initially thought the Welsh version of the film would need a Welsh language title but we ultimately decided that we loved “Wyrm” so much that it had be the title of both versions. I know there are many different iterations of the “wyrm” in folklore, but the version I was drawing on was the dragon from Beowulf. The dragon is the dominant symbol of Wales, and it’s a symbol of national pride, strength and unity, but in the local myths, dragons often have a more ambiguous and nefarious significance. There are still folk stories which carry symbolic weight today in which dragons protect villages – for a price, and I wanted to draw on that idea in the context of a horror film.

WP: What else influenced your storytelling here – this fairly remote, fairly traditional society, but one with a strange secret and codes of behaviour surrounding it? Some of the horror, and the beauty, reminded me a lot of a short story by L.T.C. Rolt called Cwm Garon – I don’t know if you know it – but it has the same sense of something unspeakable, something secretive linked to the Welsh landscape which lays claim to people (though outsiders, in this case).

CW: I love Cwm Garon. In fact, I first came across it in an anthology of folk horror stories edited by Richard Wells, who designed our titles and poster. It’s a wonderful story. In terms of specific Welsh influences, there’s also the work of Arthur Machen and two wonderful Welsh language folk horror films directed by Wil Aaron called Gwaed Ar Y Ser (Blood on the Stars) and O’r Ddaear Hen (From the Old Earth). In terms of British horror, stuff like Blood on Satan’s Claw and Requiem for a Village were at the forefront of my mind, as were films like The Shout, Frightmare, Straight on Till Morning, And Soon the Darkness etc..

The writer Kim Newman said that folk horror is often created from townies visiting the countryside, which I think is absolutely correct. It’s where much of the sense of isolation, paranoia and discomfort come from. It’s why films like Straw Dogs can feel like folk horror, even though they’re clearly going for something different. But we shot this film in my hometown, the place where I spent the first twenty years of my life. So I was approaching it from a different perspective – that of an insider who left and came back, which itself comes with a range of mixed feelings.

WP: The film manages, in a very subtle way, to suggest that whatever code or ritual is being passed down through the generations in this village, something is not working as it should. That adds to the horror, as it implies this ritual, if we can call it that, is no longer effective. Is that a fair interpretation?

CW: Absolutely. I didn’t want the film to show the first or last time this ritual happened – I wanted it to feel like it had become all-too familiar to the participants, almost to the point where it’s now a frustration or annoyance. But, as you noted, the wrinkle is the suggestion that the frequency of the ritual is increasing, which starts to destabilise the established dynamic between the parties and hopefully increase the sense of portent. Why is it becoming more frequent? When will it not be enough?

WP: Speaking of subtlety: did you always know you wouldn’t actually ‘show’ the horror itself? Tell us about that.

CW: The guiding principle throughout was author Ramsey Campbell’s comments about the stories of M.R. James: “[they] show just enough to suggest far worse.” Practically speaking, we couldn’t have shown anything on the budget we had so it was never an option, but I don’t think I would have wanted to anyway. The title tells us what the creature is, so there’s no ambiguity about that, but we still have room to imagine ourselves how it would actually look. I often think of the scene in Kill List where Neil Maskell’s character reacts to a horrifing video – we don’t see what’s on the video, we just see his petrified reaction. It’s such a powerful and disturbing moment.

WP: Have you been pleased with the reception of your film, and where next for The Wyrm..? Do you have plans for any new projects?

CW: I’ve wanted to make a film since I was a child, but I was always scared that it was something I wouldn’t be able to do. I’ve written scripts for years but never done anything with them. My son was born in 2021 and I didn’t want him to grow up and realise that his father gave up on his dream, so I knew I had to get out of my own way and just do it. So, given how much making the film meant to me, a part of me was nervous about putting it out in the world, but the reaction has been better than I could have ever wished for. People have been so kind about the film and I am so grateful to everyone who has taken the time to watch it and to the programmers, distributors, writers and podcasters who have supported it. I feel genuinely emotional and overwhelmed when I think of everyone who has helped make this whole thing happen.

As for new projects, Julien and I are working on something at the moment that we’re both dying to speak about, but we don’t want to say anything until it’s fully confirmed. We will hopefully have some news to share shortly. For now, I’ll just say it’s another Welsh-language project in a similar register to The Wyrm...

For more information on The Wyrm of Pen Bwlch Barras, you can check out the official website.