It’s really encouraging that more and more short films are being picked up for general release of late. Hopefully gone are the days when someone’s groundbreaking project, full of blood, sweat and tears, could only ever disappear from sight after its festival run. So it’s great that Arrow – so often the benchmark for cult film, new releases and just generally what’s worth seeing – are now joining in on this, making a fresh batch of short films available via their Arrow Player service. Here’s what you can expect from three of their newest titles.

Itch

Ever heard the expression ‘an itch you can’t scratch’? Well that’s given very literal form in Itch, a film clearly reaching for a retro, exploitation feel whilst simultaneously keeping things comparatively low-key, and very stylish throughout. It’s a funny thing: like clowns, you tend to see far more nuns in (horror) cinema than you ever do out in the wild; our story as such takes place in a convent. Itch tells the story of a novice nun, Sister Jude, about to seal the deal and take her vow of chastity. However, when we see her at prayer, she’s behaving in a way which strikes the Mother Superior as rather indecorous: to put it bluntly, she’s scratching at her skin so much, she even starts raking at her thighs, lifting her skirt. During Mass! Jude tries hard to distract herself from this compulsive itch, but she cannot stop: strange, soft-focus, rather scandalous dreams trouble her, too, and before long, her skin is starting to break and bleed.

But why is this happening? As it turns out, Jude doesn’t need a psychotherapist to decode her dreams or her compulsions: the issue is lust. Jude is having uncontrollable feelings towards another of the sisters, and clearly, a crisis is approaching in terms of her wellbeing, her behaviour – and her impending vows.

Either dreamy and unreal or sharp, crisp and unsettling, there are lots of engaging visual details in Itch which focus us on its different aspect, real or imagined. And, whilst there have been plenty of nunsploitation films down through the years, things are a bit different here: the film is just not titillating, not at all, turning out instead to be a stark and troubling film which borders more on body horror than Visions of Ecstasy. The use of black and white is a bold choice, too, not negating the body horror, but presenting it in a slightly more subtle way than it might otherwise appear in colour.

Smile

By sheer coincidence I’m sure, Smile is another short film focused on the extreme loneliness and introspection of a vulnerable young woman, but this time we are planted firmly in the modern world, with its technology which both closes the distance between people, and entrenches it. Clearly a person struggling with depression – the bottles of pills in the bathroom certainly seem to point towards this – Anna (Konstantina Mantelos) is brushing her teeth, listening to a well-meaning but upsetting voicemail from her mother, who wonders aloud: whatever happened to the happy little girl she used to be? There’s no call back: Anna continues on through her day, alone, but she’s troubled by something. There’s a noise at the door of her apartment: maybe someone is trying to get in, but, who, or what?

Smile is only seven minutes long, but quickly establishes its protagonist as sympathetic whilst also deeply troubled; Anna’s pained, troubled expression does give way to something else, but that in itself is part of her nightmare, maybe of this spectre of an untroubled past coming back to haunt her. Great SFX, too, makes this a vivid and shocking few minutes, doing just enough to escalate the horror but always feeling rather hefty and introspective. This is a great calling card by director Joanna Tsanis – and horror fans will also be interested in spotting the Ashley Laurence cameo.

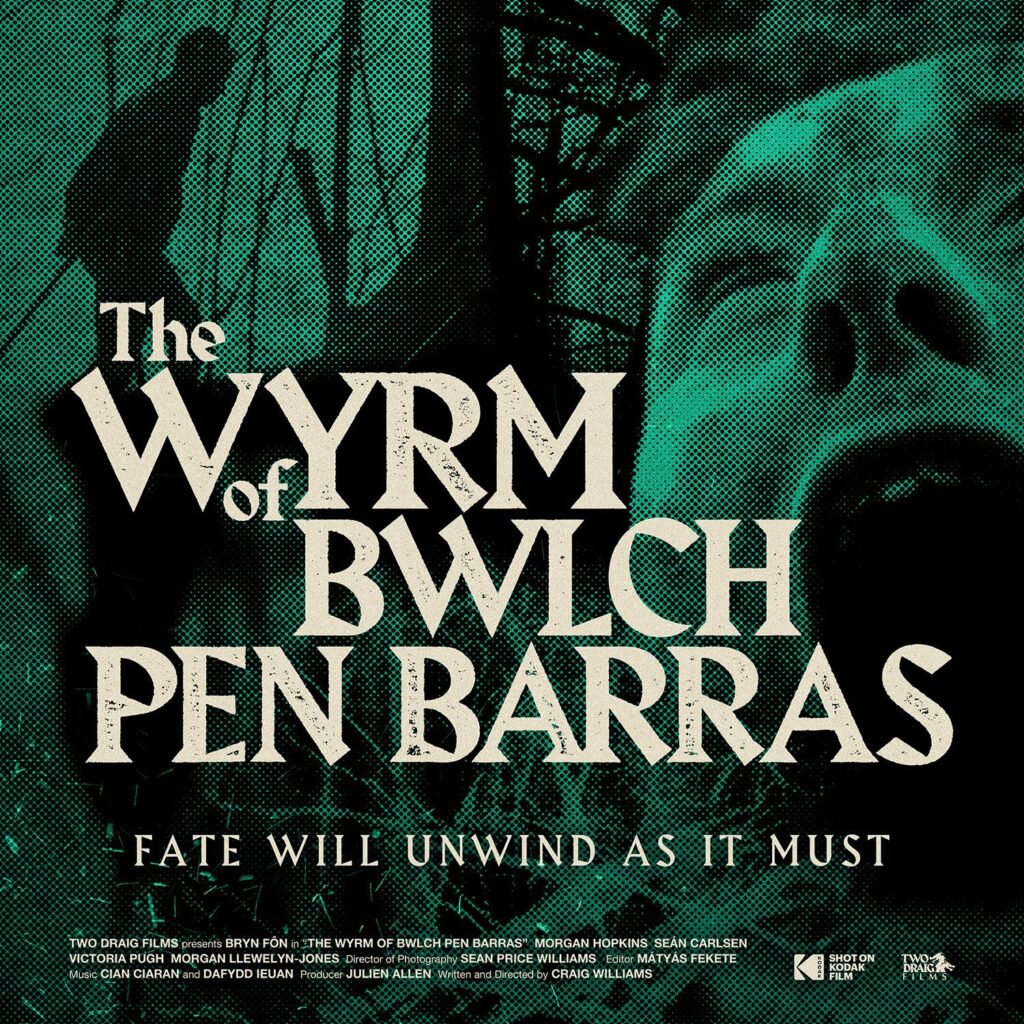

The Wyrm of Bwlch Pen Barras

.

..and the absolute stand-film of this collection, for me, is the super-subtle, thought-provoking and disconcerting Wyrm of Bwlch Pen Barras, which opens with some stellar 70s folk horror vibes, right from the text and the appealing Kodak film grain of the opening credits (which, if it turned out was for a lost film by Piers Haggard, wouldn’t feel at all amiss). But, again, The Wyrm of Bwlch Pen Barras is bang up to date, and the more disturbing for it. This isn’t the 70s at all; a man is woken from sleep by a phone ringing, which he answers, barely speaking back, but immediately begins to get ready to leave the house. His wife clearly expects this call, though she notes that it doesn’t seem to have been long since ‘it’ needed to happen last time.

She’s not otherwise included in this, though, and her husband Gwyn (Bryn Fôn) is soon headed out, picking up what seem to him (and perhaps to us) a rather ragtag bunch of other local men who are also needed for some duty, now once more ahead of them – something to be dreaded.

To say much more is to risk spoilering the film – which would be unforgiveable – but know this: the film’s bleak intersection of clearly ancient, onerous traditions and modern concerns (there are hints that one of the small party is there, unwillingly there, for some community transgression) makes for a surprisingly involving concept, with so much to unpack. The film is not heavy on dialogue, and it is a mostly very quiet film through and through, but says and does enough to suggest a whole world beyond itself, one which rewards further consideration. It doles its questions out thoughtfully and carefully; it leaves us to ponder, but doesn’t give us the comfort of full closure, which speaks to the confidence of writer and director Craig Williams. The Wyrm of Bwlch Pen Barras is laden with atmosphere, too, much of which comes from allowing the landscape to do the talking – it was filmed in, and pardon my bias, the most beautiful country in the world, and is also presented in the Welsh language.

This film really is testament to what short films can do, with its clear characterisation, minimal, but at times wonderfully poetic dialogue, and its world of terrible possibilities hanging in the ether, barely acknowledged or spoken of, but undeniably there in the world of the film, and threatening to recur – perhaps quicker than these men would wish.

Arrow’s Sharp Shorts are available now on Arrow Player. For more details, please click here.