I Care a Lot is a story of utterly dismal, conscience-free people doing spectacularly well for themselves; on several occasions, it mentions the old adage (or variants thereof) that, in life, you take or you are taken. It’s a light-touch but often galling examination of the ‘American Dream’ which, when it comes down to it, rewards enterprise and hard wealth gotten by any means. The film is described in many of the usual places as a comedy, but – as entertaining as it is – it’s no comedy, not to my mind. It’s eminently watchable, and yet it’s far too appalling to laugh at, and certainly too appalling to laugh with. It’s not a satire, either, because despite its fantastical (even horror movie) turns, the backbone of its plot is not just plausible, it’s a going concern.

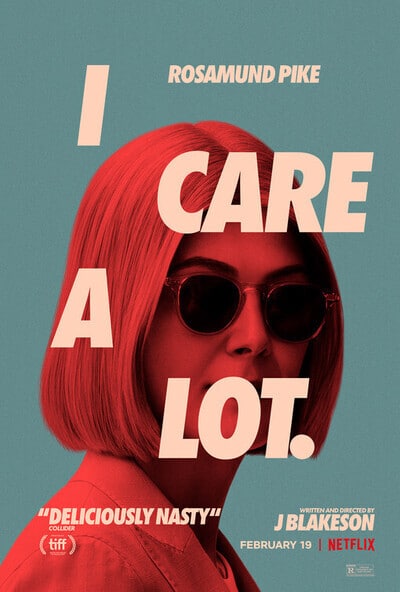

It tells the story of Marla Grayson, a kind of everywoman figure for a system engendered to care for the elderly and vulnerable, but, as the US legal guardianship model is almost inevitably ripe for exploitation, guardians have unprecedented power and access to people’s lives which is not always in the ward’s best interests whatsoever. Marla Grayson is a court-appointed legal warden, whose job is to take over and ‘care’ for people no longer able to care for themselves. The revulsion is almost instant. From the second you see Marla’s sharp, blonde bob and designer clothes (she’s often filmed from behind) then hear her assured, jargon-rich language and calm, confident tone, it’s absolutely easy to hate her, a feeling which Rosamund Pike maintains with some panache throughout.

Marla is simply doing what she does; it’s all in a day’s work. She’s ticking away nicely: preventing children from visiting their elderly parents because it’s not ‘in their best interests’, seizing and selling a lifetime of savings and real estate and paying herself out of the proceeds. Then, she is presented with what the stooges and know-alls in the trade refer to as a ‘cherry’. This simply means an older person with significant means, but no trace of an inconvenient family to prevent them getting misrepresented to the court as incapacitated (crooked doctors are, of course, integral in all of this). Perfect! Marla and her equally dreadful partner Fran (Eiza González) begin scoping out the unsuspecting woman, Jennifer Peterson (a phenomenal Dianne Wiest, even if it would have been even more phenomenal to see more of her). Miss Peterson looks like a ‘cherry’, alright. No husband. No kids. Nice house. Nice assets. Marla and Fran, enthused, discuss their next steps: in short, this means getting a medical report to assert that she is in the early stages of dementia, then locking her up in a home. When Marla finds out that Jennifer has a safety security box with even more of a haul inside, she begins to hope and pray that this is her ticket to the kinds of money she has always felt she deserves. In a genuinely unpleasant scene, the older lady is bamboozled by official documents and taken to a retirement village; they always come quietly when they see the paperwork, Marla smiles.

Everything seems to be going perfectly, but – when Fran is at the house choosing swatches ready for the house sale – a taxi arrives for Miss Peterson. Fran explains that she has moved, but the driver seems perplexed. It seems that Miss Peterson was expected at a rendezvous with…hang on, does she have family? It seems that she does. It also seems that the secret family have the kind of cash, connections and clout to cause some significant problems for Ms Grayson and her until-now very successful grift.

When Roman (Peter Dinklage) and his associates enter the fray, the film becomes less of a rather strangely bright and breezy sack-beating about how we as a culture have allowed our eldest to be treated, and more of a battle of rather well-matched adversaries. There are no moral winners here; although Roman is genuinely concerned about ‘Miss Peterson’, he couldn’t care less about the other people of her age who are getting turned over, a point which is reiterated throughout the film and more so at the film’s end. Likewise, Marla’s devotion to Fran is her own Achilles Heel, but it hardly makes her into a good person – although, at some points, the film seems to be trying to get us to applaud Marla’s undoubted ingenuity, which was a bridge too far for me. I was less than enthused by Marla’s feminist speech after she deals with the hot-headed lawyer, too: as a tale of ‘sisters doing it for themselves’, it barely works, because it’s just too hard to applaud this. However, a good balance between characters and plot developments means that we trot past any major writing concerns in almost no time, and a few more high-tension interludes command the interest too (even if this doesn’t engender any positive feelings for anyone involved).

The last act, perhaps, asks a great deal, pushing proceedings as far as they could feasibly go; this, too, is a big ask in terms of character arcs. But the finale, I feel, is a superb way of bringing the focus back to the nub of the whole plot, re-introducing an aspect which has been almost forgotten and offering something which felt quite cathartic and – dare I say it – right. I would maybe stretch things too far myself if I mentioned Les Liaisons Dangereuses here, but there is something of that; there’s a sense of one’s smartness and sins coming back to you in the end. A saddening, maddening film, I Care a Lot perhaps makes light of misery in some respects, but then if you see past the entertainment, it does have its own grim points to make.

I Care a Lot (2020) is available now on VOD such as Amazon Prime and Netflix.