Eraserhead is a film which has been around for over four decades now: its influences can be traced down through all of those decades, in projects by creatives as disparate as Frank Henenlotter and Peter Gabriel (I’d argue, anyway). So it’s difficult to know how to introduce the film, assuming anyone reading this feature hasn’t already seen it. I’ll try, but no promises. It’s a definite oddity, born out of film school and art school ‘let’s try it’ mentalities, experimental to the point of more or less ditching dialogue in favour of prioritising fantastic photography and aesthetics (its script was a mere 22 pages long). As such, a film like this is never going to be for everyone. Looking back, it feels like as much of an anomaly now as it must have then. In an era of gaudy exploitation cinema and lurid colour, it opted for black and white; in an era of extremes where extreme cinema was balanced by box office schmaltz, it eschews both approaches. If it has anything in common with anything, then I guess it’s Godard at his most surreal, but again – that hardly comes close either. How is this going so far?

So much as Erasherhead has a plot, it follows the everyday existence of one Henry (Jack Nance), a printer at a factory, though he’s ‘on vacation’ when we meet him. Some vacation: he knocks around on the outskirts of an industrial sprawl, the only flora sprouting haphazardly out of parts of his apartment. He’s dating a sweet girl called Mary (Charlotte Stewart) but a meal round at her and the folks’ goes badly awry when it transpires she’s recently given birth to a…well, she’s given birth to something, and poor Henry is apparently the father. This hastens their union, and they both begin doing their best to look after the little critter, its continual mewling soon driving a wedge between them. Still, at least there’s some escapism for Henry, in the form of a lady who lives behind the radiator and performs songs. Is this heaven? Possibly. Up against the other settings here, it’s as good as it gets.

That such a humdrum yarn – albeit one with absurd twists to it – should still be so engaging is testament to the film’s strangely-involving feel. It moves quite languidly through whatever action it offers, but then pauses to ponder over some meticulous, if inexplicable little detail. We end up pondering over same. In this film, you can chart the development of Lynch’s intense, fever-dream kind of emphasis on internal states; things always feel about to lurch into the ugly or incomprehensible, a dream which starts one way but spins off in another. Then, a moment of ebullient insanity will pop up, and the mood lightens, temporarily. All of this takes place against a backdrop of soulless urban misery, literally overshadowing the chintzy remnants of a 1950s lifestyle. Whilst all of this is going on, Henry looks as confused and nervous as we are, a kind of everyman in a mad world. The theme of male anxiety, particularly with regards to child-rearing, is written all over this film and it’s almost touching, even where the film veers into body horror. Lynch’s daughter Jennifer has suggested that her own difficult babyhood (she was born with club feet which needed surgical correction) fed into the Eraserhead vision, and its wide-eyed protagonist’s struggles with the baby’s needs. It’s possible, but then again, the ratio of real life to film will probably never be known decisively.

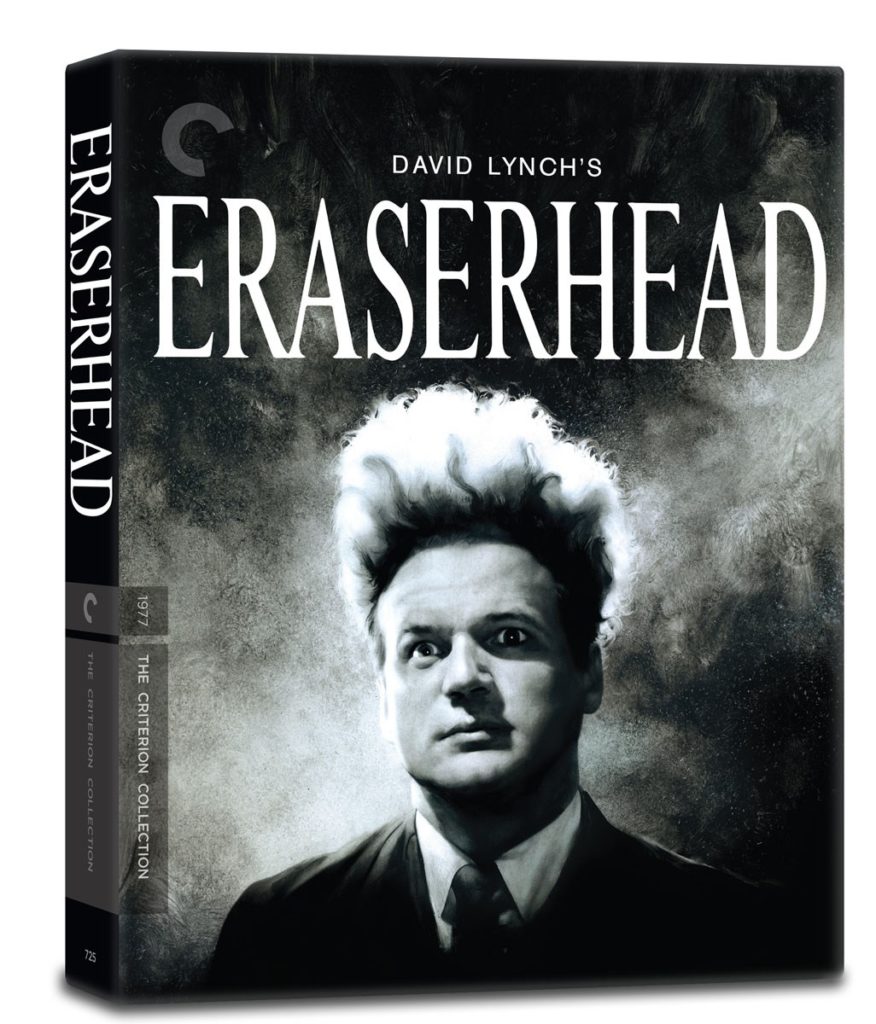

This Criterion Collection restoration has been done with the director’s blessing: it looks great, with sharp definition, rich blacks and heavy shadows. Nothing is washed out, everything is punched in. However, in those scenes where there is some film grain, this hasn’t been destroyed and all in all, this transfer is good quality. It sounds great, too, albeit that its proto-industrial soundscape is almost unbearable in places. (Good. It should dwarf everything.) Alongside the feature, there are a number of Lunch short films included on the release. These date from the 1960s, some not much more than fragments, and some more fleshed-out. We get: Six Men Getting Sick; The Alphabet; The Grandmother; The Amputee, and Premonitions Following an Evil Deed. There is also a section containing ‘supplements’, archive features which include an 85-minute ‘Making Of Eraserhead’ feature, narrated by Lynch himself. The package looks great, the film is timeless, and if you’ve put off purchasing Eraserhead so far, then this would be the definitive buy.

Eraserhead 4K will be released by The Criterion Collection on October 19th, 2020. For more information and to pre-order (UK) please click here. For US orders, please click here.