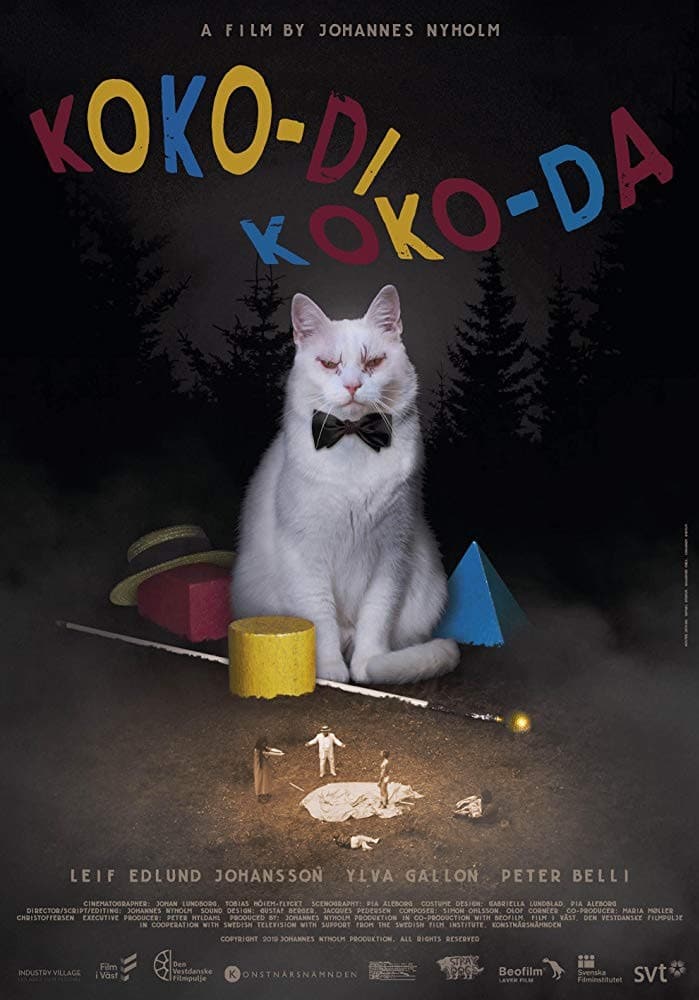

‘Koko-di koko-da’ – this is a tune sung by an oddly jaunty showman making his way through the woods with a group of equally odd companions, as the opening credits introduce us to this film. Koko-di Koko-da is an often challenging, if always creative watch which uses unorthodox means to explore very real experiences. Our odd little group remains in the woods – for now.

We shift our attention to a young family – father Tobias (Leif Edlund), mother Elin (Ylva Gallon) and daughter Maja (Katarina Jakobson), who are out for a day at the coast when Elin gets sick after eating some bad mussels. It’s serious enough that she needs to get airlifted to hospital, but she begins to recover, staying in hospital overnight (which means that it’s Maja’s eighth birthday when they wake up).

But they can’t wake her. In a genuinely upsetting long take, they realise that Maja has died in her sleep after eating some of the same mussels as her mother. An abrupt cut silences Elin’s desperate screams and time, it seems, has passed. Without the anchor of their mutual love for their daughter, Tobias and Elin’s relationship has lurched into the petty and the peevish. Negative gender stereotypes abound: Elin has turned into a passive-aggressive complainer, Tobias into a blend of heroic masculinity and sullen torpor. Perhaps because of this – or perhaps despite this – they have decided to go on a camping trip to try and reconnect with one another. Early signs are not promising.

Worse still, the strange band of people from the opening credits arrive on-site and they are savagely, pointlessly cruel, treating the pursuit and torture of the pair as a pastime: you get the impression they have done this many times before, so assured are they in their actions. Or are they? What are they? Overlaying a genuine, realistic portrayal of grief, Koko-di Koko-da transforms into a circular fever dream of power and powerlessness.

Even attempting to look past the tragic central event which underpins the issues which plague Tobias and Elin, this is potentially a deeply unsettling viewing experience for an audience. The film moves forwards and backwards in time, unpicking previous scenes, repeating other scenes and destabilising the narrative throughout. The magical, the optimistic, or even the faintly normal gives way endlessly to harsh (un)realities; for example an animated insert, providing a childlike way of expressing the unpalatable, is brought back down to earth with a loud bump. Like a scale tipping first one way and then another, the film displaces moments of calm in favour of something startling – though as it progresses, even the moments of calm are horrifying, a waiting game for the next ordeal. The characters who appear from the darkness to torment the couple are an interesting group, acting like a new, dark fairy tale version of the stages of grief: the animal, the mute, the brute and the showman encapsulating a range of covert feelings or ways of behaving.

Bringing this back down to earth even more sharply is the fact that Tobias and Elin are far from sympathetic characters for large parts of this film. Yes, their love for their daughter is clear, but without her they are not the same people and seem fated to go through the same process forever, never understanding it or undergoing the kind of awakening you expect, even in such surreal styles of storytelling. Tobias, however, does start to realise something is going on as the overnight camping trip goes on and on and on, and he tries to break the cycle – though he does this purely selfishly at first, with Elin going through a stage during the mid-point of the film where she seems less and less like a character in her own right at all, just an annoying, inert being who fails to understand Tobias’s alarm. This impression of her is dispensed with it a truly beautiful, truly moving sequence later in the film, one of the finest developments on offer here.

Koko-di Koko-da is a relentless exploration of loss, where new miseries and terrors overlap the old and realism jostles for position with the surreal. Much of it has a kind of Waiting for Godot vibe, in the sense that you have two people trapped in the question, ‘how do we ever move on?’ However, the grisly, nightmarish aspects of the film transform the question into something altogether more pressing and fearful. This is by no means an easy, enjoyable watch and god knows it’s not for everyone, but it’s always a thought-provoking experience.

Koko-di Koko-da will be exclusively released to BFI player, Blu-ray and digital on 7 September 2020. For more information, click here.