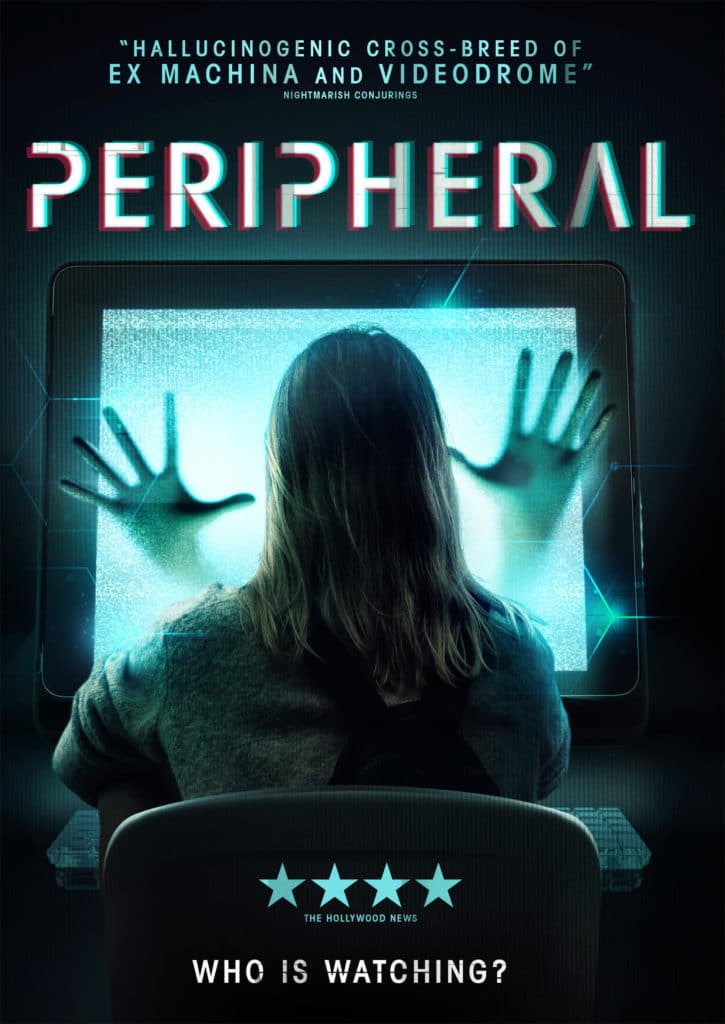

I’ve enjoyed following director Paul Hyett’s work to date: The Seasoning House and Howl both made great use of confined locations and escalating ordeals, whilst I had some misgivings with the latter film; we have something different altogether with Peripheral, however, as we delve into ‘tech terror’, combining age-old anxieties with the shock of the new.

Bobbi Johnson (Hannah Arterton) is an author whose first novel has become the voice of the disaffected in a UK now rife with protests, invoking her words and her ideas as gospel. How to live up to that? Writer’s block has taken hold, represented by a blank page staring back at her (from what looks an awful lot like a nod to the typewriters of Naked Lunch). Ironic, given she’s trying to write something about the perils of success, at a point when she can no longer pay her own bills. Her publisher, Jordan, argues that she ought to ditch the analogue and start using editing software: it’s not an idea Bobbi is much taken with, but needs must and a deadline looms, so she agrees.

The set-up she receives is pretty extraordinary – a kind of virtual reality Lament Configuration; not only is it there to facilitate her writing, it’s there to demand it, even to live-edit it. This in itself is a ghastly prospect – and the continued presence of junkie ex Dylan (Habit’s Elliot James Langridge) and someone persistently delivering numbered video cassettes to her home address isn’t making the process any easier.

The new hardware keeps on coming and coming; Bobbi becomes less and less certain of how much of this writing is even hers, given the machine takes it upon itself to alter key aspects of her narrative. As she slips into occasional drug relapses (no thanks to Dylan) the divide between author and machine becomes increasingly blurred.

Peripheral is a visually smart, colourful film with an equally smart script: it uses humour (Bobbi’s attempts to change the looming computer to UK English; the cardboard blinkers she creates for herself) but despite this, it links fairly effortlessly to bigger, more fundamental questions about writing itself. It examines the idea of writing – or any creative process – as pure product, with agent Jordan (Belinda Stewart-Wilson) as the calm, clinical voice of the moneymakers, bulldozing Bobbi’s concerns about her ‘craft’ as pure nonsense. Just get it done. The machine will sort it out.

The imagined tech itself, which supersedes current capabilities but not by much, calls on some extensive CGI sequences, the likes of which are never for everybody, but these are as pacy as the rest of the film, and don’t detract from the story; likewise, some of the visual metaphors are pretty blunt, but in a quick, savvy film which deviates into fantasy as often as it does, it still feels in keeping with the whole. It knows its stuff. There’s a level of knowledge and exasperation here which propels the film onwards, exploring the ideas of fame, celebrity, creativity and inspiration in a world increasingly hostile to creators. And, whilst this film doesn’t delve to the grisly levels of The Seasoning House, it still explores aspects of body horror – the use of a body as palimpsest adds a note of graphic, unsettling unease.

Hyett has struck a good balance here, then, between the flashy futuristic and good, old-fashioned claustrophobia. As tech horror continues to develop and reflect contemporary concerns, this love letter to Cronenberg is grim but stylish, and well worth a watch.

Peripheral will be released on August 3rd, 2020.