By guest contributor Matt Rogerson

The phenomenon of liminal spaces is one that traditionally exists in both Architecture and Psychology. With its beginnings in the term ‘liminality’, conceived by Arnold Van Gennep in his book Rites de Passage (1909) and determined to mean a passageway, be it from one physical location, situation, status or time period to another, the liminal space is generally considered to be a place or state of change (1). In psychology, liminal spaces represent the transitional and the transformative, where we find ourselves in between one state of being and another. In architecture they might relate to hallways, waiting rooms or bus stations; any threshold between one place and the next, not meant to dwell in but to pass through, a way-point on our journey. In some cases, a liminal space can exist simultaneously in both the geographical and psychological sense. Consider an abandoned building, in a state of uncertain transition between owners, or a cemetery, a cold and uneasy place that people hurry through at night, haunted by the sense of proximity to the spiritual plane.

In horror, the liminal space is often to be feared. It evokes feelings of unease and dread, and can represent a portal not just between places but time, space and other dimensions. Between the known and the unknown.

Between the living and the dead…

In the hands of accomplished horror creators, liminal spaces can also be so much more. In Kyle Edward Ball’s Skinamarink (2023), a family home becomes at once claustrophobic and impossibly vast, a mundane environment turned into a haunting, alien domain. Kane Parsons’ Backroom (2022 to date), which has spanned from online creepypasta to YouTube series to a forthcoming A24 movie (2) offers its audience “a maze-like expanse of hallways and open spaces that seem almost infinite…(with) a constant sensation of dread”(3). In literature, Mark Z Danielewski’s novel House of Leaves (2000) deals with liminal spaces in a number of inventive ways, from the living, mutating expanse of unlit passageways in the Navidson house, to re-creating those liminal spaces on the page through creative text positioning (4), to the extensive use of footnotes to establish a parallel narrative running through the book.

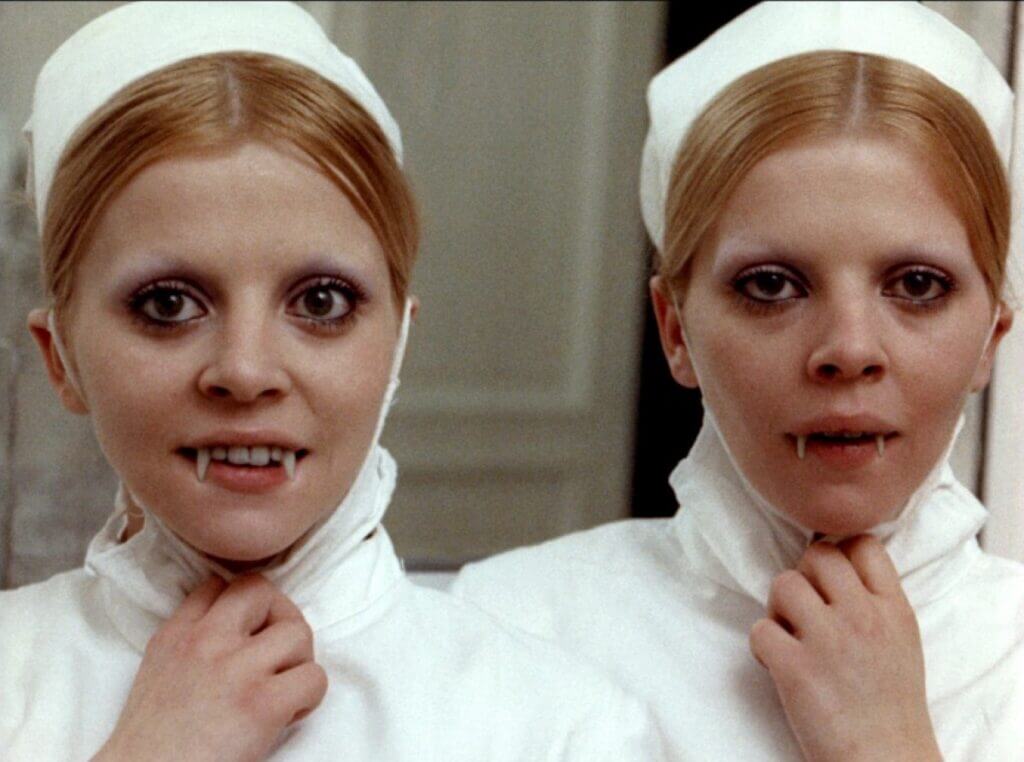

Liminal spaces are an intrinsic component of the cinema of Jean Rollin, the French surrealist and eroticist horror filmmaker whose works were often derided at the time of their release, but have undergone a period of artistic recuperation in recent years. His locations, often recurring (such as the Pourville-sur-Mer beach in Dieppe, where many of his filmic narratives begin and end) and often signifying the transition from life to death, are as important to his oeuvre as any character, inciting incident or overt narrative signposting. One of the oft-levelled criticisms of Rollin is that his films are aimless and uncompromisingly languid; plot, pacing and narrative cast aside in favour of disconnected images of nudity, sex and death. This is largely unfair, with the director’s films tackling socio-political, feminist, queer and existential themes that the audience is encouraged to find and follow – Rollin will direct you towards meaning, but he won’t hold your hand. One way of determining the rich variety in Rollin’s films is in his use of liminality. Rollin’s vampires, zombies, succubae, pirates, escapees and virginal young women are drawn to liminal spaces in each of his films, in service of a variety of themes, subtexts and messages. According to Tara Ogle, Director of Architecture for Page & Turnbull, sometimes liminal spaces “are liminal in a temporal way, that occupy a space between use and disuse, past and present, transitioning from one identity to another” (5); Rollin’s various portals and vestibules exist in each of these states and more, as evidenced by the following examples.

Cemeteries exhibit their discomfiting liminality in La rose de fer (1973) and Lèvres de sang (1975). In the former, a young woman and her new lover become trapped in a cemetery overnight, and the membrane between the worlds of the living and dead grows thin overnight, prompting madness and murder. In the latter, protagonist Frédéric attempts to have his childhood acquaintance Jennifer (believed to be a vampire) accepted by a society ruled by superstition and paranoia, and it involves bringing her and her followers from a remote chateau to Paris, via a cemetery.

Deighan notes that “coffins and coffin-like boxes often serve as portals or gateways, generally transporting characters through time and space.”(6) Rollin frequently features vampires in his films, and explores the use of coffins and coffin-like boxes in a number of sub-textual ways. In Le frisson des vampires (1971), a grandfather clock is used by vampire Isolde to visit and seduce uncertain newlywed Isle. The liminal space in Rollin’s third vampire movie represents a passageway from the realm of the undead to that of the living, but it also speaks to a queer-coded transformative experience: the Sapphic awakening of Isle, who represents generations of women that have entered into heterosexual marriage for the sake of expectation and appearances, tragically denying their sexuality and hiding their authenticity. While the clock might represent Isolde’s passage between realms, it is also the liminal space that allows Isle to undergo her transition and to ‘come out of the closet’.

Les Démoniaques (1974) is almost expressionist in its depiction of a dangerous stretch of France’s Coast. Smooth, obelisk-like rocks rise from the sand into the sky, looming over everything like ancient Gods. The shipwrecked boats look like the skeletal remains of giants long since killed, their ribcages split open under the bright blue moon and the endless night. This is a place where many have come to transition unwillingly from life to death. It is only after two young girls (the titular Demoniacs) are defiled and murdered by pirates that they are able to escape to a location yet further adrift from the real world; an old monastery, where the Devil and his minions await them, and bring gifts of healing and vengeance. The film’s beach (the very same Dieppe beach that Rollin returned to time and again, though it is unrecognizable here) acts not just as a liminal space between life and afterlife, but between rape and revenge, between the wronged and their wrath.

The liminal spaces in many of Rollin’s films are indicative of the socio-political climate in France at the time. Rollin’s first film was released during the 1968 Paris riots, where students and workers brought the city (and other parts of the country) to a stand-still for an entire month. Paris was an oppressive place, with a heavy gendarme presence and was unsafe for many marginalized people, particularly its LGBTQ+ community. This prompted a wave of countercultural urban migration – “le retour à la terre (‘the return to the land’)”(7) – with utopian aims of escaping de Gaulle’s government and living freely in rural communes (8). This is reflected across Rollin’s oeuvre, from his vampire films to his ‘escape’ cycle (La Nuit des Traquées,1980; Les Paumées du Petit Matin, 1981), as his liminal spaces provide his characters with passageways between metropolitan hell and rural idyll.

Perhaps most interesting is Rollin’s use of liminality to represent the transition of a young transgender girl (via queer-coded subtext). In La vampire nue (1970), antagonist Georges keeps his young ward captive (the nameless, titular vampire girl) first in his Paris mansion then later in his rural estate, where he subjects her to experiments as he seeks a ‘cure’ for her condition. Rollin’s critics suggested his sexualized vampires as nothing more than exploitative eroticism, but evidence in Rollin’s second film suggests themes of liberation, of queerness and potentially of the plight of the transgender child. Such children are often cut off from the world and denied necessary care by abusive parents who assert that they know ‘what is best for them’. This is all acutely resonant of Rollin’s narrative: the young ‘vampire’ is held captive by Georges until he can find a ‘cure’ for her condition, a thinly-veiled metaphor for the abusive practice of conversion therapy. His mansion is awash with signs and symbols of broken childhood. When the girl is revealed to be a harmless but fantastical creature, and her community come to rescue her, they do so by means of liminal spaces. It is somewhere between Rollin’s crumbling chateau and Pourville-sur-Mer beach that a portal exists, one that denies all known laws of physics. This liminal space, represented by a red velvet curtain, is both an otherworldly portal and an avenue for the young girl’s safety, and the most concrete example yet of Ogle’s assertion of the liminal space representing “transitioning from one identity to another”(9) in Rollin’s work.

Jean Rollin’s use of liminal spaces is impressively displayed across his entire filmography and concerns both the architectural and the psychological to convey the transitional and the transformative in a myriad of ways. They are portals between places, between realities, between states of being, and sometimes all at once. We can find liminality at the heart of everything he created…just don’t dwell there too long.

The son of a Video Nasties Pirate (and grandson of a censorious Roman Catholic matriarch), Matt Rogerson became a fan of genre cinema at a disturbingly early age. Decades later, his writing often concerns the intersection between the Roman Catholic faith and the horror film. He features in House of Leaves Publishing’s Filtered Reality: The Progenitors and Evolution of Found Footage Horror, Diabolique Magazine, Horror Homeroom, Dread Central, Horrified Magazine and Beyond the Void. Matt’s first two books, The Vatican versus Horror Movies and Faith in the films of Lucio Fulci will be published by McFarland & Co.

References:

1 Grindle, Mike (2024) The Psychology of Liminal Spaces: On the transitional zones between “what was” and “what’s next” [online] Available at: https://medium.com/counterarts/the-psychology-of-liminal-spaces-7aa1f650e7d5 [Accessed 9 April 2024]

2 Grobar, Matt (2023) ‘The Backrooms’ Horror Film Based On Viral Shorts By 17-Year-Old Kane Parsons In Works At A24, Atomic Monster, Chernin & 21 Laps [online] Available at: https://deadline.com/2023/02/the-backrooms-a24-developing-feature-based-on-viral-horror-shorts-1235249413/ [Accessed 9 April 2024]

3 Millican, Joshua (2023) Skinamarink: Why Liminal Horror May Be the Perfect Subgenre For the Times [online] Available at: https://gamerant.com/skinamarink-liminal-horror-perfect-post-pandemic-subgenre/ [Accessed 9 April 2024]

4 Brant, Lewis (2022) The Horror of Liminal Spaces [online] Available at: https://www.dreadcentral.com/news/437408/the-horror-of-liminal-spaces/ [Accessed 10 April 2024]

5 Ogle, cited by Hoyt, Angela (2024) Why Do Liminal Spaces Feel So Unsettling, Yet So Familiar? [online] Available at: https://science.howstuffworks.com/engineering/architecture/liminal-spaces [Accessed 9 April 2024]

6 Deighan, Samm (2017) “The Thing in the Coffin: Jean Rollin’s Female Vampire as Romantic Liberator” In: S.Deighan, ed., Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin Toronto: Spectacular Optical, 113

7 Farmer, Sarah (2020) Rural Inventions: The French Countryside after 1945. Oxford University Press, 54

8 Farmer, 54.

9 Ogle.