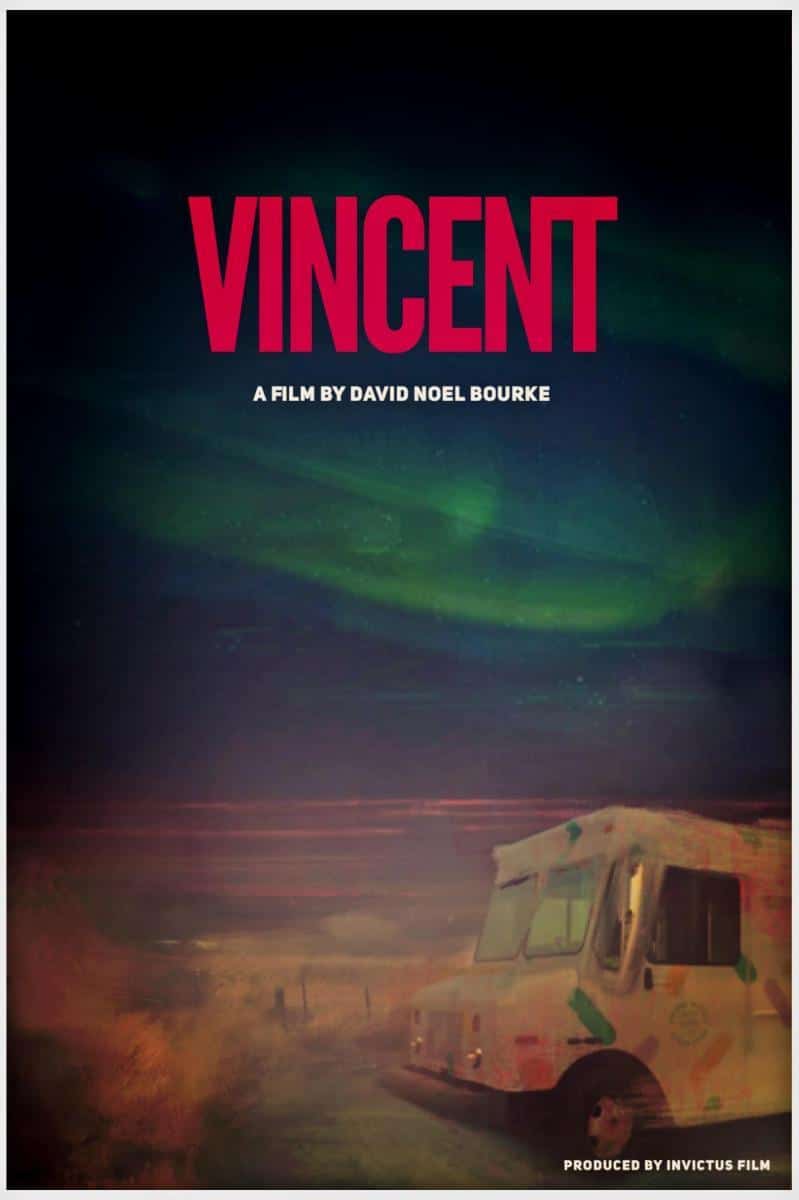

Strange goings-on are pressing in at the edges in Vincent (2023): disappearances, despair, double lives. But despite these blue-tinged, Nordic hints of horror, this turns out to be an immensely warm, often touching film about friendship which absolutely deserves to be seen. This is one of those indie cinema gems which you keep on reviewing films in order to find.

Opening with the Boris Karloff quote, “The monster was the best friend I ever had”, you could say that the film sets out its stall early on: it interrogates the whole idea of monsters, from the cinematic monsters beloved of the horror genre (and a young protagonist who adores them as much as Karloff evidently did) to more everyday monsters, or monstrous behaviour, which requires no supernaturalism whatsoever. We meet the Vincent of the title (Mikkel Vadsholt) in strange circumstances: it looks like he is drinking blood through a straw, and then, soon after, pausing to dig an animal grave in the woods, when he hits something in his ice-cream van. Yep, Vincent sells ice-cream, and if that makes you suspicious, then a police officer who pulls him on a routine stop after a local disappearance is thinking the same thing. Vincent doesn’t help himself: he stammers over his answers to questions, and he’s carrying a lot of kids’ comics for reasons he can’t really identify, except to say that he likes children, and children like comics. That’s enough for Zebastian, the cop (Joachim Knop) to decide to keep an eye on him afterwards, even though the disappearance in question concerns an elderly man. Some things just take precedence.

Meanwhile, we’re also introduced to Viggo (Herman Knop), a monster-loving teenager who, in his way, is just as isolated and prone to suspicion as the older man, alienated and bullied by his peers (the film is a masterclass in bullies you soon love to hate) and, though smart, barely able to enunciate what’s going on with him. Vincent and Viggo’s paths cross just after he is attacked by the same group of bullies who harangue him in class; Vincent sees the assault and stops to ask if Viggo is okay. He offers to drive him home; a few moments into his instilled fear of strangers, Viggo is bruised enough and sad enough to take him up on the offer.

Steadily, the film unfolds details of Viggo’s family life: his nightmares, his problems, and most of all the recent trauma he has experienced as his mother has just filed for divorce from his father, a man who perhaps means well but indulges his cruel, belligerent side in order to ‘do well’, causing more upset as he goes. If Zebastian – whom we’ve already met – really wants to do right by his son, then his prejudices and beliefs impair the process. Primarily via him, it asks us to consider our preconceptions about Vincent. Can a man of a certain age simply like children, or do we see something dark in that? This is all aside from any potential other readings of Vincent’s character, and the subtle, questionable hints that he is not ordinary in other respects: how much of what we’re seeing could be explained away? Is he a threat?

Along the way, as an unorthodox friendship develops between Viggo and Vincent, we’re privy to a range of oblivious, unrealistic, even self-obsessed adults. Vincent might have the trappings of being an odd guy, but at least he notices what’s going on around him; there’s a lot of ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions’ in this film, a lot of which impacts upon Viggo, a kid it’s impossible not to feel for thanks to a beautiful performance by Knop, where earnest emotion can only find its way to the surface at extraordinary moments. This is ably balanced by Vadsholt, whose Vincent is an incredibly well-observed, earnest character throughout. The unorthodox friendship here is wonderful, and the film as a whole is cleverly written and edited, full of little surprises, clues and inversions.

And, despite remaining largely on the periphery of the horror genre, the film knows horror, referencing it throughout: not only can Viggo reel off the titles of his favourite escapist horror films, but you could debate a few nods to Let The Right One In (albeit without that film’s more overt generic features), some of the dark humour of the lonely ice-cream seller in Chocolate Strawberry Vanilla, and a few nods to The Shining plus (I’d argue) a reference to Kinski’s Nosferatu, only put across in a much less florid way – even if keeping the same sentiment.

There’s just the right amount of ambiguity in Vincent: this is an accomplished, charming film which is humane and heartfelt at all times, whatever other questions it holds onto. It’s a real joy, and the best of all things film-wise – a real surprise.

Vincent (2023) is looking for distribution and festival screenings now: for more details, check out @TheVincentMovie on Twitter (or X, these days) and take it from there.