By Gabby Foor

Shuffling, shambling or sprinting, our relationship with the zombie has changed as fast and furiously as someone bitten by one. In the last twenty-five years we have seen an evolution of the nearly one-hundred-year love affair with the undead in all their various forms, and twenty years ago (counting to its United States release) a virus that turned its host into what we deemed “The Infected” tore through our screens via Danny Boyle’s low budget apocalyptic thriller titled 28 Days Later. Popularizing the viral trend and powering up the undead, on a budget of only $8,000,000 this film managed to turn our heads from what we expected from zombies, and it seems we never looked back. In the house, in a heartbeat, with some of the most memorable kills, haunting images of the infected and a score we can think back to when we want to hear horror, 28 Days Later deserves a twenty-year homecoming to celebrate what it did for the undead and to acknowledge how the franchise never got the closure it so rightfully deserved.

We open to footage of rioting, executions, violence and military intervention, playing for a chimp strapped down and hooked up to nodes at the Cambridge Primate Research Centre. Three activists take it upon themselves to break into the lab to gather evidence of animal testing and mistreatment. A scientist catches them in the act and attempts to reach security, but he’s stopped. He tries to warn the activists that the chimps are infected, highly contagious, infected only with what he deems “rage.” Only inciting the activists more, they release the animals and are immediately attacked and infected, spreading it to one another, and we are left with the parting message, “28 days later…”

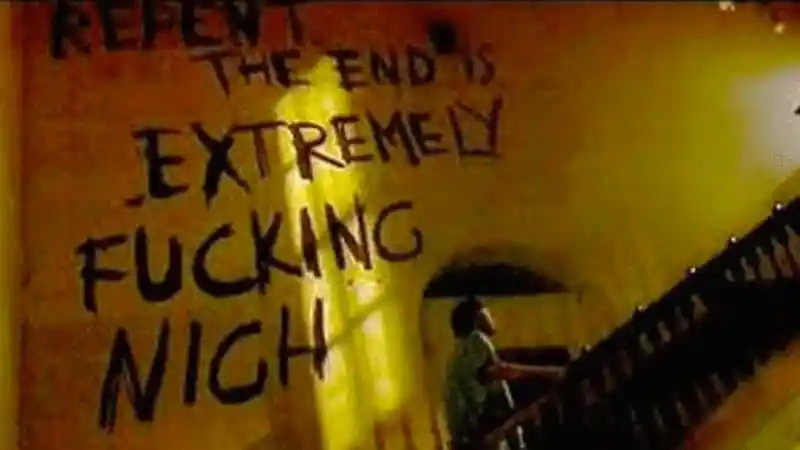

We then see Jim (Cillian Murphy) awakening in a (fun fact, real) UK hospital, naked and abandoned. Harshly lit, closely shot, he finds the hospital deserted, phone lines down and signs of disaster everywhere as Jim wanders the building collecting clothes and supplies. As he surveys London, he sees no one, hears nothing, finds rubble everywhere on the streets and can’t find another survivor. Wandering an abandoned city, to a moody score you could catch in any survival horror game now, Jim is our last man: finding newspaper articles about evacuation and missing person posters, he’s starting to come to terms with what might have happened here. “The end is extremely fucking nigh,” painted on a wall gives Jim the message as he enters an abandoned church, filled with piles of bodies, some of which spring to life when Jim calls out.

As Jim explores further, he stumbles upon more infected and begins to realize these people are far from normal. Striking one with a bag that would knock any average person out, Jim is panicked and still guilty at hitting the infected man even as he continues to lunge and snap at him. Jim flees the church with the infected not far behind when suddenly, Molotov cocktails light up the streets. Masked survivors call out to Jim to make his way to them as they set the infected ablaze, not stopping until they’ve blown up a gas station with the infected inside. Better than a double tap, I say. Jim’s saviors are Mark (Noah Huntley) and Selena (Naomie Harris), who get the story that Jim was in an accident on his bike that left him in a coma during these events. Mark’s got some bad news, he says, and Selena follows with the story: the virus, an infection in the blood they say has taken over, and by the time evacuation came, it was too late. The army is overrun and there has been an exodus; reports of the infected in Paris were recounted, and now, there is no news at all. Jim’s the first uninfected they’ve encountered in a week.

Zombies: An Evolution

Let’s address this first of all: many fans are loath to classify 28 Days Later’s infected as actual zombies, merely human beings infected with a behaviour-altering virus (the film does base some of its symptoms on the real-life Ebola virus). However, the mindless, en masse behaviour as the Infected move around in hordes; the loss of reasoning power and intelligence; then of course the bite factor, adapted now to spread infection more than to feed – the infected are, for all intents and purposes, zombies, and they mark a long sequence of developments to this particular movie monster.

The first on-screen zombie sighting can be dated back as early as 1932. White Zombie, directed by Victor Halperin and starring Bela Lugosi, is supposedly the first on-screen trace of a human woman, given a tonic to kill her, being brought back to life as a zombie. 1943’s I Walked with a Zombie brings us closer to hoodoo and voodoo origins, as does 1966’s Plague of the Zombies. An all-important movie that gives credence to voodoo and Haitian culture respectively is Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988), a film which focuses heavily on cultural respect and religious ceremonies instead of using their cultural elements as “sensational plot devices.” The zombie begins as a more magical being, a once living person given a tonic or else reanimated through ritual, an idea which comes from a more cultural, religious and regional legend which through literature and film has now spread to us.

Once Romero reaches and reinvents the genre, and with the inspiration of the epic I Am Legend (the novel not the film), we see our zombies begin to evolve. In Night of the Living Dead (1968)The East Coast has fallen and these monsters are hordes ready to devour. Romero continued to expand his vision in the wildly popular Dawn of the Dead (1978), which continues to show the aftermath, with survivors banding together in a mall to take shelter. The 80s and 90s brought us some other zombie classics – away from Romero’s ongoing work in that decade – with cult classics such as Peter Jackson’s surprise Dead Alive (1992) which is supposedly one of the goriest films ever made. Give or take a few outliers such as this one, however, the zombies we recognize in cinema even now have many similarities to Romero’s zombies. However, the key evolutions that seem to go back and forth relate largely to two factors: speed and science.

28 Days Later arguably re-popularized the sprinting, screaming zombie that you would have to be a track athlete to outrun, but there’s an argument out there on the web on which movie truly started the movement; 28 Days Later reinvigorated it, but didn’t create it. The argument goes between Nightmare City (1980) and Return of the Living Dead (1985) as the originators of the “quickly moving zombie”, another controversy this film faces. Then, when 28 Days Later rises in the early 2000s, it kickstarts a movement of films and videogames that were ready to pounce on a genre moving towards science and illness, focusing on viral and then fungal transmission, and away from the magic and ritual that initially brought our dead to life.

From Outbreak to Apocalypse

The zombie timeline also applies to how we viewed them as a phenomenon. In the earliest zombie films, that is pre-Romero, zombies are no unstoppable wave or super powered creature, they are the risen dead and can be put back to rest. The evolution of zombies and their reanimation and transmission method has also caused a shift where zombies seem to signal the end of the world in all cases. In older zombie films small towns, homes or just individuals were plagued by zombies and they weren’t nearly as fearsome, in decades-old makeup, shuffling and shambling. Romero’s call in Night of the Living Dead that the Eastern seaboard had fallen victim to waves of mass murder was the first echo of an apocalypse, and this cryptic plague reanimating cadavers is our first trace of a viral zombie.

28 Days Later seemed to begin the world ending trend of zombies that followed with a string of box office and television series that mimicked the same cataclysmic end to our society that a zombie virus might bring. With Night of the Living Dead landing right in the middle of the Vietnam War and 28 Days Later landing in the US after a great national tragedy, it seems the walking dead connect to us when we feel like reality is coming undone. Scenes depicting missing posters under a large building were a cause for controversy in the U.S. as it stirred memories of recent losses during 9/11. Boyle, having made the film prior, says he would have shot certain opening scenes differently with that in mind had he made the film after the attacks.

In nightmarish fashion, we watch as the government and military unravel and feel the sense of what things would be without the societal safety nets we inherently assume will be there during an emergency. We see after 28 Days Later films like the Resident Evil franchise, Dawn of the Dead (2004), Shaun of the Dead (2004), The Walking Dead (2010) and World War Z (2013) pile up the bodies, literally and figuratively, giving instances of corporations, governments and the CDC itself falling to their knees in the face of these outbreaks. It show us that in the event that we become our own worst enemy, there may be little we can do to stop it. Jim’s idea that “there’s always a government” shows how rooted we are in our societal nets and how the idea that the most well-funded and supported militaries and programs would fall in the face of cataclysmic disease is often simply unthinkable.

Nothing quite encapsulates this breakdown like the simple sinister phrase as spoken by one of the last remaining military personnel in the post-virus Britain of 28 Days Later, “I promised them women.” People are now currency, in a world where the only hope of rebuilding comes at the cost of the permission of those necessary to it. The idea of this full surrender – that the military would turn against civilians and institute their own breeding program – is horrifying and can briefly remind you that maybe the infected aren’t the most frightening thing hunting the streets, another Romero lesson well learned in Day of the Dead (1985). This scenes of Cillian Murphy using guerilla warfare against the soldiers to get his female captives free from a lifetime imprisonment has a very special score called “In the House, in a Heartbeat” that is easily one of the most recognizable modern horror themes, with its soft piano and foreboding guitar. It makes for an epic, bizarre climax of survivors half naked or dressed in ball gowns pitted against their would-be saviors turned captors.

A Franchise Unfinished

With 28 Days Later grossing $82 million worldwide on its modest budget of $8 million, the film was a not only a commercial success but a critical one. Audiences and reviewers alike concurred that the film was a standout and could satiate fans’ appetites for zombie violence. The film also served as a springboard for Murphy’s career, as he would shortly go on to star in thrillers like Red Eye (2005) and Batman Begins (2005) before later being cast in Inception (2020) and probably his biggest claim to fame, the TV series Peaky Blinders (2013+). Four years later the 28 Days Later sequel, 28 Weeks Later (2007) brought in a more visible cast and an even larger budget. With nearly double its predecessor’s cash and stars like Jeremy Renner, Robert Carlyle, Imogen Poots and Rose Byrne, the more star studded and obviously more expensive sequel was still successful, grossing $65 million worldwide and maintaining positive audience and critical reviews. Then – it all stopped.

Rumors floated around all the way up until last year that a sequel script could be in the making. Both Murphy and Boyle have been vocal that they would be interested in a third film, but have yet to solidify any details. As the UK celebrated its 20th year anniversary with 28 Days Later articles pouring out asking about the possibility of a sequel, there’s nothing exactly concrete besides a very vacant and mysterious IMDB page titled 28 Months Later. There was no shortage for zombie action in both movies and games in the lurch between 28 Weeks Later and the present, but there was a film that appeared which did take an angle on how the Rage Virus might have played out.

A film called The Cured, directed by David Freyne, was part of its own not-so-popular string of zombie action, supposedly connected to a film called The Third Wave that Freyne was working towards. Starring Elliot Page and Sam Keeley, The Cured came out in 2017 and had all the similar markings to 28 Days Later but claimed it was not part of the franchise. In it, the “Maze Virus” (sounds similar doesn’t it?) has terrorized citizens for years but now with the promise of a cure, 75% of the infected can return (in this case to Ireland), with all their memories of what they did as infected, to civilized society. The other 25% are considered immune and beyond saving. But society doesn’t believe the cured can be dependable, or non-violent. We see some of the best and mostly worst of human behavior in 28 Days and 28 Weeks Later, so the reality in The Cured is that those cured aren’t welcome home: they’re not to be trusted. This film also brings about the idea of “zombie rights” and whether or not the uncured should be euthanized, being that their consciousness resides within them still, or whether or not the cured should be a protected group with more rights upon their return. The film garnered a paltry $323,000 at the box office and average reviews, unfortunately not leaving it a strong enough standalone film and no entrant into the 28 Days Later franchise for any street credit despite some interesting ideas.

Closing Thoughts

28 Days Later wasn’t only a zombie film. An emotional piece with a breakneck timeline that allowed no grieving, the film touched on loss and survival on a personal level. Stories of trampling evacuations and harrowing escapes, inspired by real unrest across the globe, make for emotional retellings of discord and death in the film, and makes each character worth investing in, no matter how long they last. The idea of a military turned more than corrupt and women as currency turns the dystopian nightmare riddled with the dead even darker, and opens up to what, as Selena would say, you would be willing to do in a heartbeat. Yet even in all of this expressive storytelling amongst the chaos and a historic performance by Murphy, the infected still surface as the stars of the show, leading us to ask some questions about where we are, where we’re going, and why we enjoy it so much.

What makes a zombie? What makes fast zombies more appealing now? What about the specialized zombies we see in games? What makes them so fascinating to us still? Our fixation on the dead has lasted a lifetime and nearly a century in film, it seems the zombie isn’t going anywhere. With new voices coming from foreign directors like Train to Busan (2016) and Kingdom (2019) it looks like the zombie evolution will continue, whether we see a 28 Days Later sequel or not. 28 Days Later will remain the catalyst of this age for fast, ferocious, zombified monsters, the popularization of viral spread and the savagery of societal and governmental collapse. Deserving of a 28 Months Later, I hope that this empty IMDB page comes to fruition soon, with the return of a director with vision and Jim on his journey again to survive a plague supposedly defeated. No other movie can fill the gaps left by this franchise and fans and critics are hungry for more. Don’t make us wait 8 more years so it’s 28 Years Later, please. I think the fans are ready to rage now.