Friend of the World (2020) starts with a few moments of that kind of angst which can only come from a place of relative practical comfort. Hence, as we see a woman meander back and forth against a beautiful, sunny backdrop, a female voice ponders her own lack of engagement with the world; she wants to ‘really live’, she says. Well, however equally meandering the film which follows, it’s yet another case of the old adage, ‘be careful what you wish for’. Though getting to the crux of that is a fairly arduous process, in a film which is so keen to overlay genre with experiment, symbolism and profundity that it has to heave its way even to the fifty-minute mark.

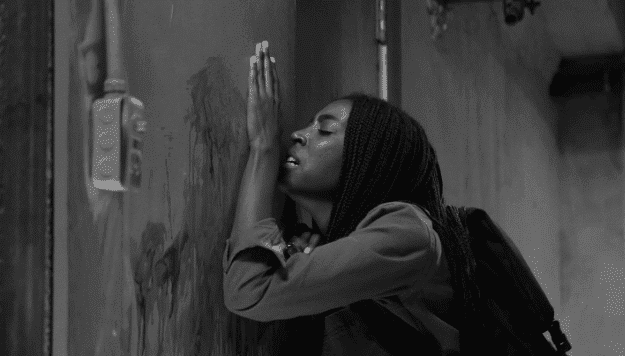

In the first chapter, titled Ripping The Band Aid, a woman – our narrator from earlier – comes to, in a basement full of rather tranquil-looking corpses. She seems to be the only survivor of whatever-this-was, so she’s quickly up and about, trying to escape from a place where people look like they may have – sheltered? Or been locked in? Who knows, and this lot aren’t telling anymore, at least not on their own behalf. And then we’re straight into another chapter – Boy Meets Girl – as our protagonist’s escape efforts founder and she falls asleep, or passes out, both activities which she finds ample time to do. She’s awoken by a man looming over her – an old-time, military guy, who seems, or at least claims, to be rather au fait with what is going on beyond the walls.

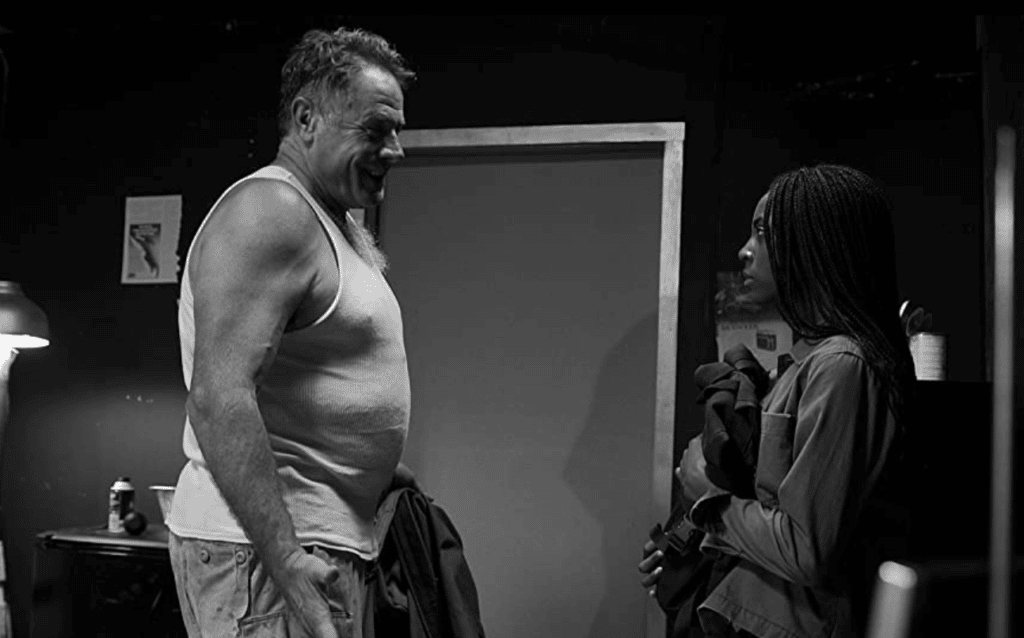

They talk, falteringly: the girl, Keaton (“we only go by last names here”) turns out to be a filmmaker, which explains the fragmentary footage at the beginning; it was her work. She’s also the greatest artiste in the world, as the guy – Gore – points out to her, seeing as how everyone else is now dead. They also talk about the rather more pressing matter of why the world has seemingly ended; there’s another chapter break here (I stopped writing their titles down at this point). Gore, in his de facto role as verbal exposition guy, has a go at explaining, as he does elsewhere in the film; he claims some evidence for his version of events, which he presents to his unwitting companion.

So this film is a post-apocalyptic story with a very lo-fi style: there is the germ of an interesting justification for all of this upheaval in what is, in other key respects, a bit of a genre film staple. Director Brian Patrick Butler has clearly decided to focus on two characters and their experiences, rather than providing any sense of the scale or severity of threat without; you get a handful of other people, and their ‘condition’ is more about inducing trippy uncertainty into proceedings – contact with them causes hallucinatory experiences – than physical menace or similar. Okay, fair enough: 10 Cloverfield Lane (2016), which feels like this film’s predecessor in some respects, sustains a sense of dynamism and drive throughout its own runtime through careful, clever suggestion. But perhaps other restrictions, or simply other aims, lead Friend of the World away from a straightforward story of building paranoia and uncertainty, and towards something far closer to arthouse. Via these more experimental aspects, it’s perhaps aiming for Lynch, or early Cronenberg – though it doesn’t get there, as commendable a goal as these artistic and cerebral body horrors are. It’s simply stretched too thin; it’s too partial, too neither/nor.

The disconnect in acting styles which we get also seems, in its own way, to symbolise the film’s mixed messages. Keaton, actually Diane Keaton (Alexandra Slade, and yes they reference the name) plays a fairly understated role, particularly showing her skills where the film clicks into a real-time, realistic mode early on, as she tries to escape the basement. Up against this, Gore (Nick Young) is all whites-of-eyes, overblown military cliché, although he does get some quite funny, world-weary lines along the way. But he’s kept at a distance as a character, in ways which may be wholly deliberate, but come across as quite jagged. It’s an even bigger ask when he segues into providing the film’s moral message.

The black and white film and the filming itself look very good, with well-composed, well-lit shots which are easy on the eye. The use of chapters and intertitles continues to be an irritating, needless filmmaking tic, particularly unnecessary in a film which doesn’t even reach the hour mark, but overall, it’s a good looking film. And we should never punish a film for having ambition; the ambition here is commendable. It’s just that it’s part claustrophobic character study, part ragtag arthouse experiment, with blaring music and fart sounds to boot. What can audiences make of this? At one point Gore declares to Keaton, “Your film sucked – in a beautiful way”. Sure, this might well be a self-referential line, one intended to pre-empt criticism of Friend of the World, but if there is an element of heading off criticism at the pass here, then perhaps there’s also a sense that this film may not work fully well on its own merits. It badly needed to commit to something – oddness, aesthetics, or plot. A film cannot, after all, simply turn out to be an essay about film.

Friend of the World (2020) is now available to view on Apple TV and iTunes.