There’s been a run of very good music documentaries lately. This has been facilitated by the likes of Netflix and Amazon, ever hungry for new content, but regardless of the means, the best of these have been about bands with careers and fan bases of a certain vintage, making them commensurate with enough highs, lows and turning points to make for an entertaining story. Even a passing awareness of Life of Agony would suggest that they fit that bill, given they formed over thirty years ago and have enjoyed a career with very jagged highs and lows to date. So there’s plenty here for a documentary, and The Sound of Scars has its moments, though some of the decision-making on editing and emphasis turn the project into something other than a straightforward music lover’s film. In many respects, the film is far less an appreciation of the music than it is a capsule of current social mores and attitudes, via old sadness and more recent woes. It’s all about the feelings.

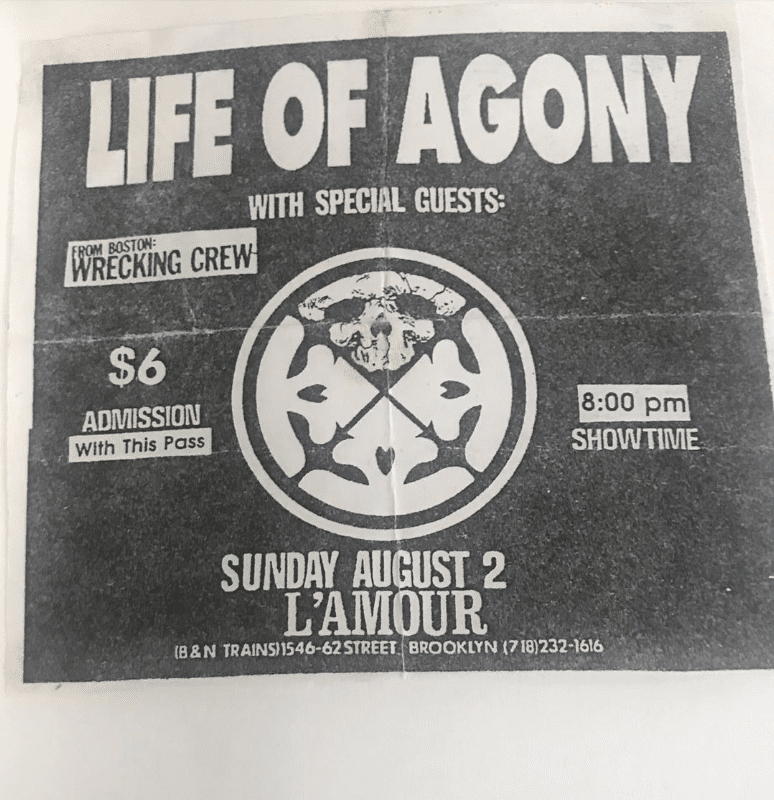

Of course, the emotional states which fed into the band were always going to figure here; that’s understood. LOA were initially so interesting for striking a formidable balance between the nascent hardcore metal scene and more heart-on-sleeve, emotional content (would it be unkind to see some aspects of proto-emo in there?) They have also long had a unique sound which I strongly associate with 90s Brooklyn: their debut was produced by Josh Silver of Type O Negative, and you can absolutely hear it in the music. Moving on somewhat from their hardcore sound by the time they recorded their magnum opus – Soul Searching Sun – in 1997, the band made something far more expansive and progressive without losing the emotional weight they’d become known for, but this high point (and close call with mainstream success) turned into a profound low with the abrupt departure of vocalist Keith Caputo, who was beaten down by the pressure.

It’s a tale as old as time, but perhaps LOA stand out here on one count: when Caputo re-joined the band some years later, it was no longer as Keith, but as Mina, as the singer had decided to come out as transgender. This fact becomes a kind of narrative frame for the film, and I’m surprised to see some reviews claim the reverse; it opens with Mina after all, who is quick to point out that Keith was only ever a ‘construct’, a hyper-masculine man amongst hyper-masculine men, and a kneejerk response to a traumatic, challenging early life. (This instantly-recognisable masculinity is present throughout the film, the blend of camaraderie and tribal warfare which means, for most women, deciding very carefully where they can stand and walk during a gig.) This introduction segues into a brief early history of the band, together with a history of the incredibly traumatic childhood experiences shared by bandmates Joey Z and his cousin Keith (and a brief note: rather than fixating on ‘deadnaming’, the film is fairly relaxed about interviewees using either ‘Keith’ or ‘Mina’ to refer to Mina Caputo, depending on what point in time is being discussed). Bassist Alan Robert is the exception here, coming from a loving and supportive family – who profess themselves baffled by his long history of depressive thought.

All of the band members are aware that their early ethos was very much ‘do unto others what has been done to us’, referring to themselves as ‘punks’ and relating how intensely violent and combative the early years of the band were. A particularly engaging section of the film relates to getting signed by Roadrunner, and the subsequent upsurge in pressure, noted particularly by Caputo who – a contested person at this point – struggled with it, alongside feelings of unhappiness relative to gender identity. It’s clear to read between the lines and see that the same diehard gender expectations which gave rise to the punching-and-kicking masculinity mentioned earlier seem to also mean that anything more sensitive or gentle is by its nature viewed as ‘feminine’ (Caputo has mentioned elsewhere that being a woman allows her to be a ‘fucking sissy’ in ways impossible whilst living as a man). That’s testament to just how entrenched a lot of these roles are – but of course, this discourse being held sacrosanct, it’s all simply affirmed, which is occasionally frustrating, especially as a more in-depth examination of the music itself isn’t really there as a counterbalance.

Sure, there are some clips of early practice sessions, early gigs and interviews – which are great to see – but these are still brief and there’s actually little detail on things like musical influences, the recording processes, tours, changing creative directions and so on. Surely if the trauma which underpins the music is seen as vital, then the end product itself deserves a little more emphasis? It’s also interesting to consider that, given the happy endings displayed in the film – loving family lives, cute kids, nice homes, personal fulfilment – the bleak emotion of the music keeps on coming. Will this always be the case? And will this ever impact upon the angst-laden sound the band has perfected? I’m also curious as to why drummer Sal Abruscato – a vital part of River Runs Red and Ugly as well as the reformed band – isn’t mentioned once; there’s only a glib comment on how the band ran through numerous drummers before Abruscato was replaced by current member, Veronica Bellino. That’s strange.

Perhaps The Sound of Scars simply isn’t the film I was expecting, because it certainly has good elements; its meandering style at least tantalises with a lot of previously-unseen footage, home video, early promos and plenty of access to most of the integral members of the classic line-up. The emphasis on problematic childhoods was always going to be there, and the film is an interesting document in the way it straddles music documentary and tell-all personal story – though, for all that, I didn’t reach the end of the film feeling like I had a deeper, more significant understanding of the individuals in the band, even whilst wishing them well: their friendships certainly come across warmly, and you’d never begrudge any of them their success. But the music still speaks for itself and for the band far more convincingly than the film does.

The Sound of Scars is now available on digital and cable platforms.