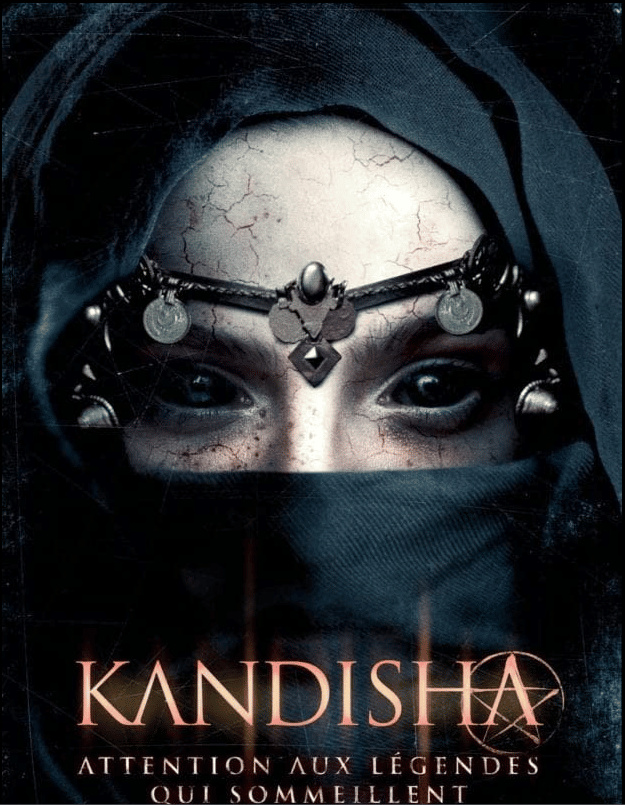

Writing and directing team Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury are another couple of filmmakers who, after the initial rise of ‘new French extremity’ in the Noughties, didn’t maintain the same prolific trajectory. Hey, it happens – as I’ve mentioned elsewhere in a feature on Martyrs, once you’ve gone that far, where is left to go? And that’s beside the more standard-issue concerns of funding and budgets, when the economy keeled over not long after the new wave broke. Bustillo and Maury did, however, go on to make more films after the mother-as-monster of Inside in 2007; there was the beautiful magic realism of Livide (2011), an entry in the ABCS of Death short films and a brief foray into Texas Chain Saw territory, before it all went quiet again. This all brings us to Kandisha, a film which opts for a Candyman/Drag Me To Hell style of occult horror, where unstoppable forces have to be, well, stopped. It does this by reaching for Moroccan folklore, emblematic of the modern, multi-ethnic cast of the film, though beyond itself the story still feels very familiar. Kandisha is somewhere between the all-out gore of Inside and the gentler, more surreal Livide, tumbling between these two.

Friends Bintou (Suzy Bemba), Morjana (Samarcande Saadi) and Amélie (Mathilde Lamusse) – or graffiti artists BAM as they like to be known – are enjoying their summer break, turning a disused building into a group art project, swapping gossip and urban myths. When Amélie uncovers the name ‘Kandisha’ during an evening’s painting, Morjana, who is of Arab descent, explains that Kandisha is a female demon, known for taking her vengeance on men. The girls joke around for a while, showing that there’s nothing new under the sun and you can summon Kandisha by simply repeating her name in front of a mirror, a bit like you-know-who. The girls head off home, but when she’s left on her own, Amélie is violently accosted by her ex boyfriend. She gets away, but not before ending up covered in blood. In a momentary rage, she uses the droplets of blood to summon Kandisha more fittingly. It seems to work; minutes later, he runs screaming into traffic and gets hit by a car. But as we all know, summoned demons are not terribly easy to control; the girls must work together to track down a specialist with some old tomes (as someone mentions, what’s going to happen when there are no grimoires left? They carry different information to the Internet.) A race against time to save the men in their lives ensures for the girls, and it would be a very short film if they weren’t reasonably unsuccessful.

Kandisha retains the high production values of previous Bustillo/Maury productions: there’s no denying that they have a great eye for composition, lighting and atmosphere, and all of these contribute to a very attractive film, urban sprawl meets exoticised folklore. But there are some issues with the plot here; I’m perfectly well aware that ‘exotic’ can be a very loaded term when it comes to mythology and folklore, particularly once we start to step away from the Northern European (and by extension North American) stories which are so often relied upon in horror cinema. But the mythology used here isn’t really developed far beyond any other more familiar fare, so it does remain rather thin, ‘just’ an exotic figure, or needs basic description attached, with Kandisha explained as a patriotic, man-hating female entity. Course, we come to Kandisha via a similarly diverse but partially-developed cast of human characters, whose initial friendship is presented to us in quite broad strokes: the girls are initially defined by themselves and to one another in class and race terms. Even accepting the fact that French screenwriters are far more overt about this kind of thing than you’d ever hear in anything British- or American-made, unless the characters using racial language were being set up as straightforward villains, their ethnicity and class are writ so large that it eclipses any more subtle traits for a good share of the film. It takes a while to feel empathy for them, despite solid performances. For the early parts of the script to talk them up, they’re rather rendered down, again in the pursuit of doing more.

The Kandisha myth itself, is, once established, a very familiar one: ask yourselves, what normally needs to happen in a film of this kind, and it probably happens, even if with a few swaps from Latin to Arabic. There are some very well-handled surreal scenes, with Kandisha taking a few different forms and the gore shifting incrementally from understated to very graphic; whilst Drag Me To Hell feels like an obvious comparison, the Raimi film makes it much clearer that it’s meant to be splattery fun, where Kandisha feels less tonally clear. But, hey, for all of these minor quibbles, it’s a perfectly watchable, largely enjoyable film, technically very well made and it doesn’t overstay its welcome by twenty minutes or more, as many films by less experienced hands do. Whilst Kandisha doesn’t break new ground and it’s not the navigation of folklore, identities and cultures it might have been, there’s enough here to entertain.

Kandisha (2020) will be released to Shudder on July 22nd 2021.