In the first decade of the new millennium, Christopher Smith – alongside his contemporaries like Neil Marshall, Simon Rumley and Ben Wheatley – formed part of a new wave of British genre cinema, delivering some of the best, or at least most-discussed horrors of the Noughties along the way. Smith’s first feature-length was Creep (2004), a grisly and often suitably cruel tale of the fallout of abuse, essentially, splicing the gritty and the fantastical in a way which really worked for me: who hasn’t felt that twist of alarm that they’re about to find themselves alone in a deserted tube or train station? Moving fairly quickly to the blackly comic Severance (2006), to Triangle (2009) and then the historical horrors of Black Death (2010), Smith established himself as a leading light, but then – almost in parallel with Neil Marshall – moved quite sharply away from genre into other fare entirely. It’s another odd parallel that, by 2020, both Marshall and Smith are back at the horror, with oddly-similar sounding titles; Marshall has brought us The Reckoning, Smith, The Banishing. Ours not to reason why this has happened right now: it could be a rekindled passion for genre, it could be personal curiosity, or it could be plain expediency. In any case, it’s been some time.

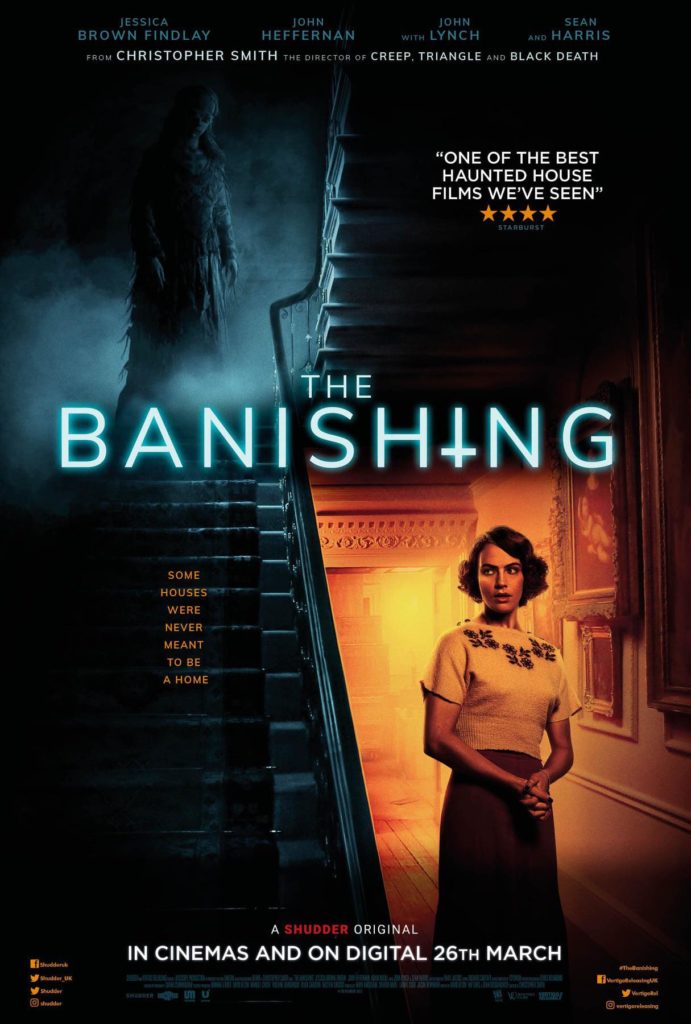

Whatever the reason for the return to the horror genre, in The Banishing Smith has made a version of the classic ‘haunted house’ movie, albeit taking as its basis the quintessential haunted house: Borley Rectory (though here tweaked to become… Morley). He clearly has awareness of the almost sacred role the Borley legend has for many people, but he has also striven to demarcate his film from the others which use the same legend for a basis; even in the past few years there have been several. As a result, The Banishing at times travels down safe, recognisable haunted house trammels, but also abruptly overreaches for new elements: this makes the film feel slow in some aspects and cramped in others. And that’s not to mention some of the more peculiar changes made here.

We start hearing a young man extolling the benefits of avoiding the ‘pleasures of the flesh’, but as he reads from his Bible, he hears a noise: investigating, he stumbles upon a savage attack taking place, with a woman being stabbed in one of the rooms of this sprawling house. This juxtaposition of sexuality and violence may appear elsewhere, but it’s established early. We catch up to this situation a little later, the man responsible – a clergyman – having committed suicide after his crime. Bishop Malachi (John Lynch) arrives and orders a swift clean-up and cover up. The Church can shift when it wants to.

Time passes and, come 1938, the house has a new incumbent: Linus (John Heffernan) is a former missionary now tasked with retrieving a congregation for the church in Morley, as the community’s religious observance has lately lapsed. His wife Marianne (Jessica Brown Findlay) and her young daughter Adelaide (Anya McKenna Bruce) join him, though it’s no time before this new domestic set-up seems strained, largely by some as-yet undiscussed past. Then of course, the strange phenomena begin: bumps in the night, creepy dolls which seem to communicate with Adelaide (it’s odd that all spectres seem to solicit the company of children; surely there are malevolent deities out there somewhere who would run a mile). Linus receives advice to investigate his house’s history “before it’s too late”, which of course it is as soon as Marianne goes poking around. Never take a house cellar unseen.

There are some very good scenes and elements in The Banishing, always the better for subtlety, the ‘almost glimpsed’ rather than the shrieking jump cut. For all that, the film seems intent to just leave its characters adrift in the house for seemingly long periods of time, having established its haunted house credentials. Marianne is frequently the film’s focus but her developing understanding of what’s happening in the house comes slowly, underpinned by more than a couple of visions and dreams and a few expeditions where she literally sorts through evidence in the house.

These elements come across at a sedate pace, but by contrast, we are then given rapid moments of exposition to move things along and to provide plot. These often come via a frankly remarkable skit on famed ghost hunter Harry Price, who first appears early on in the film, for reasons a little unclear, performing a very depressed, almost comic dance routine with an unnamed lady. He’s back a little later, rather conveniently one might say, to fill us in: Price here is played as a kind of loafing, verbose ginger spiv, a remarkable turn from Possum’s Sean Harris who thereafter becomes the film’s resident psychic. The film certainly deviates from the Borley legend in all but a few key aspects. At times, The Banishing seems to be borrowing quite heavily from Poltergeist and The Orphanage; in others, it becomes a more metaphorical haunted house, unpicking and unpacking the anxieties of the inhabitants as, for instance, Relic does. Added to this, we hear mention of fascism on the rise in Europe and this is alluded to several times, but I don’t feel that this offers much to the film, other than a minor sense of contextual unease and the excuse for a few lines of clunking anti-fascist rhetoric from Marianne. All in all, in terms of writing, there are some odd decisions here.

The Banishing is by no means an awful film: it gets its period details right, it looks good, it has a good cast who play it in earnest, and it does at least try to bring together different types and aspects of haunted house horror, which shows the willingness to try innovative things. In the end though, it’s a very mixed bag, and it does feel as though Smith has felt the effects of a long detour away from the genre: The Banishing isn’t as seamless, as secure in itself as his earlier films. But much of that comes down to the writing, as this is a maiden voyage for writers Dean Lines, David Beton and Ray Bogdanovich, each more used to penning crime dramas. Essentially, horror fans are forgiving, but fussy creatures, and when you add to an already burgeoning sub-genre, you have to know that this will be scrutinised against all the best films in that genre. The Banishing effectively weaves a few moments of satisfying unease and it clearly has ambition, but these are crowded out by some over-busy, overstretching or plain confusing choices.

THE BANISHING is available now on digital platforms and will stream on Shudder beginning 15th April.