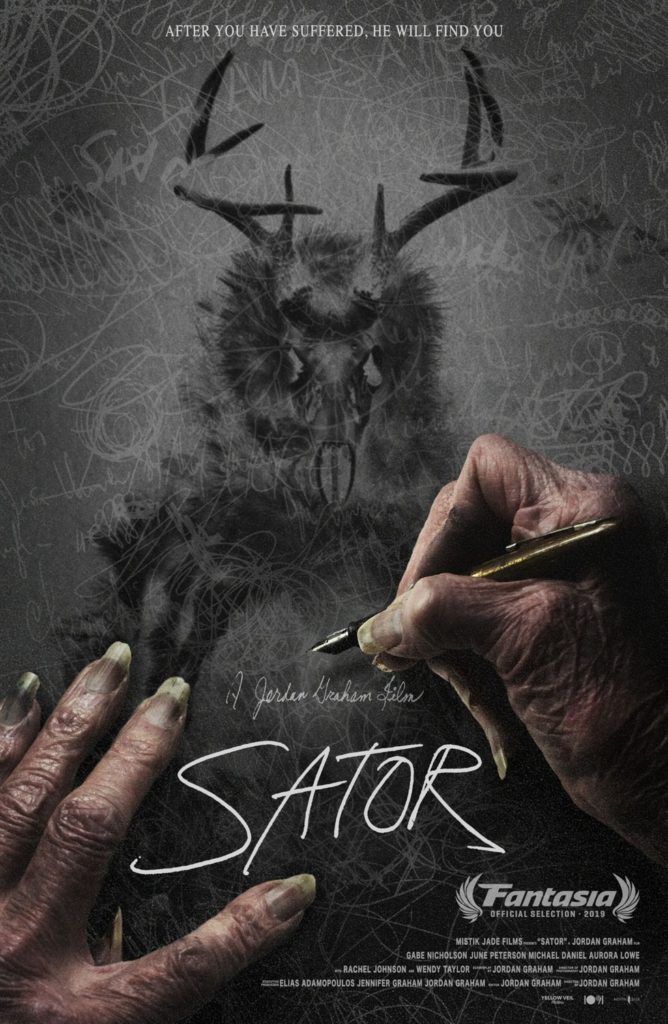

The back story of Sator (2019) is a deeply interesting one. It’s a film seven years in the making, with director Jordan Graham doing far more than even most first-timer indie directors find themselves doing (right down to building a cabin used for one of the sets). Not only this, but the film has a deep resonance with Graham, as it not only features footage of his family (with his late grandmother June Peterson also acting in the film) but also hinges upon an entity given the name of ‘Sator’ by Peterson herself; her belief in this being, and her certainty that it had a mysterious hold over the events of her life, led her to be committed to a psychiatric ward in the Sixties. Recordings of ‘Nani’ Peterson open the film; she explains that Sator is somehow ‘in charge of everything’. This real-life footage segues into the world of the film, which overlaps with the family story throughout; however, for all of the tantalising elements suggested by Nani’s tales, the film never quite rises to the framework offered, opting to front mood and aesthetics over dramatic and narrative payoff. This is fine on many levels, though I’d argue that, to truly generate scares, you need something of a cogent narrative – you need to have characters, in order to truly take note of whatever happens to them.

After a scene featuring an old, dark house full of candlelight and inhabitants in period dress to suggest, at a guess, that the being in the woods has claimed many scalps down through the centuries, we meet our main protagonist – nameless and almost wordless for the largest share of the film. His connections to others are not made clear immediately, but it seems he belongs to a rural family for whom the spectre of Sator hangs heavy – alongside a shared history of bereavements. He spends his evenings at his shack, listening to audio describing Sator’s characteristics; when another man arrives – apparently his brother – they head over to the family home, where grandma still lives. Nani still clings to folders full of automatic writing which she claims was generated by Sator and certain other beings with a mysterious, insistent interest in her and those she holds dear.

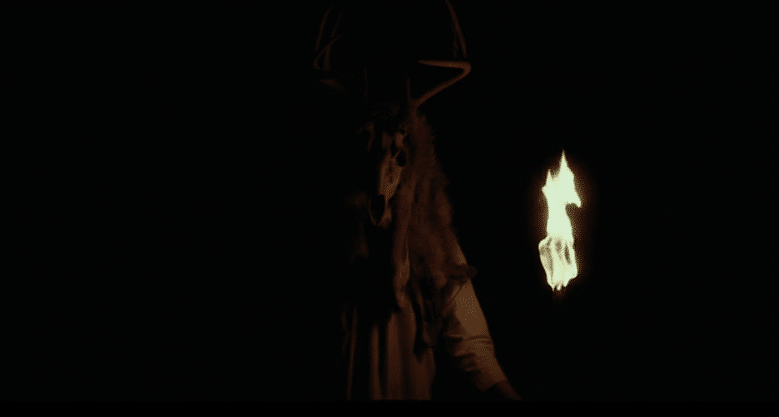

And what is this Sator, exactly? The audio files and the – now expected – analogue tapes uncovered at the house, together with Peterson’s early testimony, conspire only to …keep it all rather confusing, actually. At different times, Sator is described as a guardian, a source of surveillance, a confessor, a bane, a demon and a guide; the only thing which seems certain is that Sator has a vested interest in this isolated rural clan. There’s a suggestion that it has had some hand in the bereavements which afflicted the family, too. Then it seems that Adam, for ’tis his name (Gabriel Nicholson) is himself in Sator’s sights. Strange encounters by candle- and torchlight ensue.

Be aware: the last couple of paragraphs reads like a fairly standard brief plot synopsis, but it also feels like an ill fit, as it doesn’t really represent the tone and style of the film at all. You have to work to glean as much as this; it’s not made readily available to an audience. Dialogue typically takes the form of short, rare flourishes of conversation, and then there’s some use of monologue in the form of the excerpts of recorded voices. (I struggled with much of this, too, simply in terms of being able to make it out. Perhaps muffled voices were intended, but I don’t think the atmosphere would have been compromised by better audio clarity.) Outside of the dialogue, silence is key.

So much for how it sounds. Sator is very much a film of well-composed set pieces, folk horror leitmotifs and stunning landscapes, all bathed in the kind of natural light or candlelight which is often associated with The Witch (2015): unlucky, perhaps, as Sator was already being shot before Robert Eggers got in there. Sator certainly looks fantastic, its national park shooting location offering great examples of the inhospitable picturesque. It generates atmosphere, too, which is eminently possible, even without much story. Great Romantic paintings can be atmospheric and can convey mood; they’re not tales, though, and this roots them in a moment or a fantasy.

With regards Sator, I’d argue that waiting until after the hour mark to quickly get through some exposition is just too little and far too late. Waiting until two thirds of the way through a film makes it difficult to then invest in that character, or characters – it misses the critical period. You can appreciate the beauty, the style and the bold decision-making which turns the film away from being a re-tread of The Blair Witch Project (1999), without necessarily investing anything in Sator‘s key players. That all being said, Jordan Graham clearly has great strengths and a ferocious attachment to his peculiar vision: I’d certainly still be intrigued by anything else he may work on in future, whatever my feelings about the lack of pay-off here.

Sator will be available on Digital Download from 15th February & DVD from 22nd February and can be pre-ordered on iTunes here.