It is likely that you’ve heard some version of the term “Mind Palace Technique” used in conversation around feats of memory. Known formally as “The Method of Loci,” it is a memorization technique wherein one memorizes the layout of a building, associates an item with each location in the mental image, and later mentally retrieves each item by “walking” through the structure. A recent, popular example to point to is the Memory Palace of Benedict Cumberbatch’s titular character from BBC’s Sherlock. But the strategy dates back to ancient Rome and Greece— we have tried to impose structure on memory and our representation of mind for centuries. In Relic, director and co-writer Natalie Erika James constructs a deteriorating memory palace in physical space, creating a compelling and poignant haunted house story that asks, “If a cluttered desk is the sign of a cluttered mind, of what, then, is a decaying home?”

Edna (Robyn Nevin) is missing. Local police inform her daughter, Kay, over the phone. Kay, in turn, alerts her own, grown, daughter, Sam, and the two of them head to their ancestral abode to help with the search and to keep the home fires burning should Edna return. As Kay and Sam arrive, the house looms up and we get our first hint at the character of its absent inhabitant; this severe edifice postures like the best of haunted houses, large, proud, ageing, and lonely among the encroaching woods. Its interiors suggest further deterioration: clearly once a beautiful home, it is now marred by signs of neglect and confusion. As Kay (Emily Mortimer) tidies up, she finds food left out for a long deceased pet; the camera lingers on rotting fruit. The multitude of Post-It notes, however, is the most telling—the house is wallpapered with reminders to perform simple, daily tasks. And over everything, a creeping mold. Here is Edna’s memory palace made manifest: outwardly proud, but the contents of her home indicate dementia. Her home is metaphor for her ailing mind. The encroaching rot invades the house as it does her psyche.

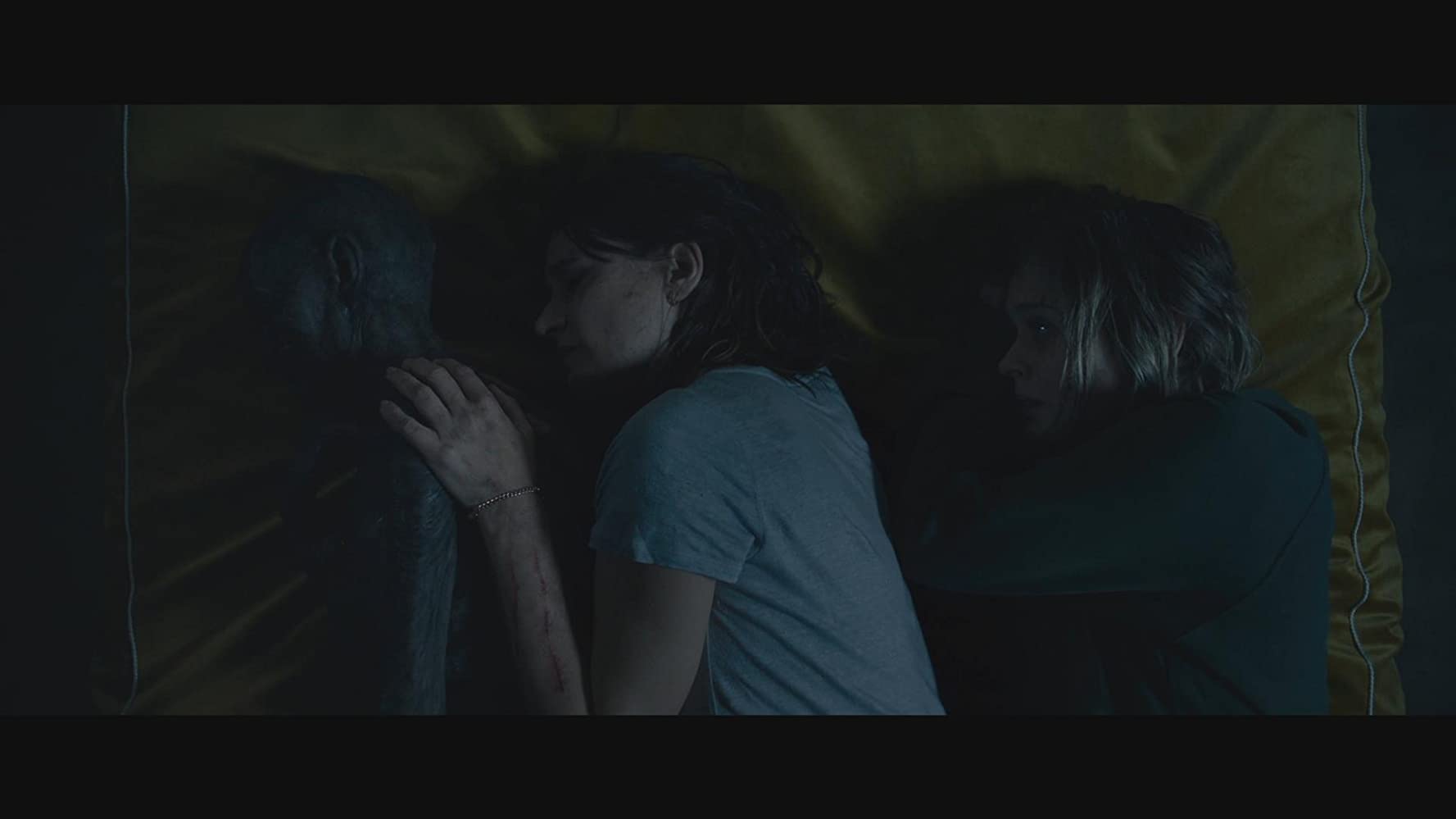

But there may be an even greater cause for concern: peppered throughout the landscape of a house and mind in decline are indications of a more immediate threat. Among the innocuous reminders are a few that take a more sinister tone. Sam finds a note imploring the reader, “Don’t Follow It”. Similarly, many doors in the home have seen the addition of new chain locks and dead bolts. Some doors have several. One in particular even includes an improvised lock utilizing a wooden spoon. Are these acts of paranoia further signs of dementia? Or do they hint at danger from an outside force? Fantastic set and sound design build on an already unsettling atmosphere until the dilapidated halls ooze dread. Seething shadows harbor an anthropoid silhouette. Creaking floorboards chorus around distinct knocks, apparently issuing from within the walls. It would seem that some sort of malignant entity stalks the house and its inhabitants. Is this incursion into Edna’s palace just further expression of her deteriorating mental state, or could it be the cause of it?

When Edna suddenly returns after three days without explanation, relief at her return is immediately swallowed by the ever-growing tension. She, like the stern facade of her home, tries to project strength, and to a certain extent is successful. In her more lucid stretches, she is whip-smart and fiercely independent. When Kay confronts her about her degrading memory, bringing up the proliferation of Post-Its all over the house, Edna simply remarks, “It’s my house, I can decorate however I want.” Moments like this allude to Edna’s wit and poise. But in spite of these moments, because of these moments, the truth that underscores these interactions is that much more painful. The Post-Its, impervious to her quips, signal that Edna is not the woman she once was, and despite her protestations, she knows it. She slips through different states of acuity, warmly dancing with her granddaughter before lapsing into confusion and anger. She is self-reliant, then suddenly so frail, painfully small and scared under her covers, insisting her daughter check for monsters beneath her bed. James paints of a striking picture of a family straining to hold together in the face of an unseen and unrelenting foe. The horror is in the family coming to terms with the fact that their loved one is slipping away.

The metaphor here is not subtle, and using horror to outsize the inherent fear in no longer recognizing the person you know and love is not particularly novel. Even so, James has managed to find a new angle to address mental health through constructing a crumbling memory palace. Utilizing its decaying house impeccably, Relic delivers all the dread of a classic, slow-burning chiller while staying true to its allegory. To be sure, it is not a traditional film about a haunted habitation. The focus is on the three women as they struggle to reconcile with their inevitable fate. Edna’s health worsens, filial relationships are tested, and all the while, menace builds to a third act crescendo that capitalizes on its central metaphor in dizzyingly thrilling fashion. Supernatural or otherwise, dementia is an intergenerational curse, and Relic spins a taut horror yarn that is equal parts heart wrenching and terrifying.

Relic (2020) will be released in the UK on 30th October 2020.