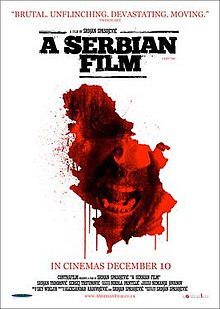

Ten years has passed very quickly in the world of independent filmmaking: in that time, there have been a lot of great films, a lot of not-so-great films, and none (to my mind) which have had so much as a fraction of the impact of A Serbian Film (Srpski film).

It was a film, like many others, made on a shoestring, one which made minimal profit, but in terms of a reputation – well. Through shockingly explicit content which was widely known about before the film’s arrival onto the festival circuit, A Serbian Film generated immense buzz, first screening at SXSW in March 2010 before becoming the common denominator in a series of panics, denunciations and cancellations, followed almost inevitably by outright bans. In many respects, for those already used to shocking content, it became the film to see; as word spread and infiltrated even the mainstream (which it did, if only a little) it built up and up until it was something of a folk tale, or a ‘double dare you’, one to get through, rather than to earnestly enjoy.

In the UK, some hesitant planned screenings, including at London’s FrightFest that summer, were pulled under increasing local and national pressure. By the time the BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) got hold of the film later in the year, it was shorn of a massive four minutes and eleven seconds before it was deemed suitable for viewing. In many respects, this is no surprise: that scene was never going to trip past the censors unchecked. Yet in other respects, the BBFC’s itchy trigger finger led to scenes being cut for things I certainly hadn’t seen in them; their vigorous pursuit of certain ideas about sexualisation got the better of them here. Meanwhile, as the BBFC were and are vigilant for the merest insinuation of impropriety, we now have a social media platform like Twitter (new and untested then; established to the point of being tawdry now) which has people openly declaring their sexual interest in minors, joining ‘communities’ and performing some agile mental gymnastics to assert that they ain’t so bad, really. Funny old world. A lot has changed in a decade, it seems.

“This whole nation is a victim…”

So what led to the creation of such a divisive film? ‘Torture porn’ had been bandied around as a term for some time by then, but never was the phrase interpreted so literally as here. Director and screenwriter Srdjan Spasojevic could easily have said quite simply that this was the film he wanted to make, and if he pushed the envelop somewhat then, so what? This was never the starting point, though. The much-vaunted rationale behind A Serbian Film was that it was a ‘political’ film. Spasojevic has said that his film was born of anger; it’s also the very antithesis of the kind of film you are supposed to make in Serbia, a country he characterises as being spoon-fed sentimentality and trope. There’s also a sense that, as Serbian cinema is so often funded from overseas, Spasojevic’s distaste for this lack of home-grown film inspired him to make a specifically Serbian film which laid waste to the norm. Well, didn’t it just. In a neat piece of parity, A Serbian Film made its own name abroad; in fact, it was months before the film actually screened in Serbia itself and even then, audiences were utterly bemused as they thought that films presented events as they should be, rather than simply as they are. If this is so, then no wonder they found A Serbian Film difficult to place…

So, okay: the film was born of rage and dissatisfaction with convention; mainstream cinema is bland, and the usual funding streams are riddled with agreed, fashionable social mores. Thing is, that could just as easily be a charge levelled at UK and US cinema, on the whole. I’m no expert on French, German or other European countries’ cinema scenes, but I wouldn’t mind betting it’s a similar picture. Imagining alternatives to the mainstream has always led viewers to more minor genres, films whose own content would very likely disqualify them from widespread approval and promotion. It’s been the benefit and the bane of horror cinema for years. All the same, though, neither US nor European cinema has ever gone as far as A Serbian Film in terms of content, despite coming from the same place, of wanting that alternative to the jaded and the saccharine. And why not?

Something else which has long been doing the rounds, again as promulgated by Spasojevic, is the idea that A Serbian Film is a ‘political allegory’, and thus it can justify its graphic narrative along those lines. Akin to another political allegory movie, György Pálfi’s Taxidermia (2006), it’s perhaps telling that the political allegory on offer depends to such a large extent on gross-out moments. My initial response to arthouse-porn-film-as-allegory was sceptical; ten years on, it’s sceptical still. I just don’t think some of the justifications match up with the choices of content, like you can pass off child rape by simply saying ‘it’s symbolic’. But, in the interests of balance, there are allusions in the film to Serbia’s standing in the world after the Yugoslav wars: Maria responds to the mention of filmmaker Vukmir by saying ‘he sounds like one of our guys from the Hague [war crimes] tribunal’. Vukmir himself justifies his project by saying Serbians can live and suffer vicariously through seeing it; Spasojevic has said that he sees his film as an equivalent to American cinema post-Vietnam, a means of exploring national trauma. Perhaps. Ask any number of film fans, and they’ll have a different idea on A Serbian Film and the efficacy of its political subtext. But whether a potent allegory or simply an exercise in pure nastiness, the film thrived chiefly on its notoriety: it’s a decidedly dismal film – artistically dismal even – where a decent enough man is hammered repeatedly into the ground by circumstances beyond his control. Only he and Maria seem in any way palatable; everyone else is the film is a caricature or a monster, or both. A Serbian Film was clearly designed to press buttons and it did so, so successfully that it broke through into mainstream media coverage, with British newspaper The Independent rhetorically asking if A Serbian Film is ‘the nastiest film ever made?’

“That’s the cinema – that’s film.”

My suspicion is that, in common with Pascal Laughier after the success of Martyrs (2008), there was simply nowhere else for Spasojevic to go after A Serbian Film. When you have gone that far, in your debut film no less, then where’s left? How do you follow that up? If you attempt to push things even more, then for one, you’d struggle; it’s also likely that you’d increasingly irritate audiences who might feel that they were simply being dragged through atrocities yet again for the sake of it. But if you radically dial down your approach and your style, then you could just as easily alienate people attracted to your extremity in the first place. It’s a tough one, and this is just one facet of the trials and tribulations impacting upon filmmakers in the current climate.

Ten years on, it’s interesting that the film is still so neatly divisive: Rotten Tomatoes has it at 2.5 stars out of five, whilst IMDb currently rates it 5.1 out of ten. It’s pretty much straight down the middle. A Serbian Film evidently isn’t a film which you have mild opinions on, certainly, and including such content is always a hell of a gamble with prospective audiences, a love or hate scenario. Risk and reputation intersect in this film. However, if (as I suspected) A Serbian Film was in some ways intended to be a calling card of some kind, a name-making film which made everyone sit up and pay attention, then it turns out that I was wrong. I had thought that, even were A Serbian Film to haemorrhage money, which it apparently did, it would nonetheless get everyone talking about Spasojevic; once indie film had lit up, the filmmaker’s notoriety would assure him a glittering career. And yet, in the decade since, there’s only one directorial credit to his name – an underwhelming entry in the ABCs of Death (2012). Perhaps Serbia is an prescriptive place to make films and is completely sewn up, just like the director said. There is a project currently in pre-production however, currently linked to Unearthed Films in the US. Titled ‘Whereout’, it’s described as a horror Western: little else is out there at the time of writing, but it would be interesting to see Spasojevic back at it, as regardless of your opinions on A Serbian Film, it’s by no means a badly-made film. It is a shame that he hasn’t worked in the past eight years whilst people with far less talent go on cranking films out, year after year after year…

I suppose that, whatever your feelings about A Serbian Film and whether or not those feelings have changed over the intervening decade, the fact that it persists and is so well-remembered by the majority of people who have seen it says something for its merits, after all. Alongside films like The Human Centipede and Martyrs before it – although these films are clearly hugely different from one another – A Serbian Film represents something about horror at that time, when a desire to escalate the brutality seemed to take hold of the scene for a while. As with all things, the wave has since rolled back; there’s less emphasis on shock and ordeal now, at least to those levels, but the unremitting pursuit of the ugly did lead to some interesting, memorable cinema. I do think that A Serbian Film is both of those things, wherever it might be on the axis between style and substance, and I’m sure it will continue to be talked about for some time to come.