As this is a detailed examination of the film, it contains spoilers.

Seldom has the sole creation of one person travelled so far and changed so many times as the story of Frankenstein (1818). Sure, horror is populated with multiple vampires, mummies and zombies, but even the best-known stories have often been woven out of pre-existing folklore. Mary Shelley’s story was, at the time in which it was written, unique; Romantic ideals about man’s relationship with nature, the burgeoning scientific developments of the day and Mary’s own distorted, mournful experiences of creating new life conspired to develop a horrific tale without real precedent. And yet, her story has itself always been pulled into new forms when brought to the screen – which it has been, often, since cinema’s earliest inception, with the first ‘liberal adaptation’ of the novel arriving as early as 1910. Subsequent generations have always want to emphasise (or even add or replace) key elements of the original novel in their own ‘liberal adaptations’. So it’s surprising that it took until as late as 1994 for a film to make the claim that it was ‘Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’, and to declare that it would follow the novel very closely.

Step forward, actor and director Kenneth Branagh. Best-known for his direction and performance in Shakespeare productions, Branagh certainly had the literary pedigree to tackle the book, although he was at the time a relatively inexperienced director beyond Shakespeare – in some respects, this shows, and the film’s rather mixed reception has often commented on its tonal shifts between horror and drama which don’t always sit well. However, for all of its flaws, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has many redeeming qualities, and does some things very well indeed. Looking back at it from a quarter of a century on, it’s interesting to note these, as well as to re-examine the film overall. For me, in a nutshell, the film’s a mixed blessing: the period setting, the cast and certain elements of faithfulness to the original plot are very bold. In other aspects, its deviations and decisions are a little exasperating. Here’s a look at how, and why.

“Strange and harrowing must be his story…”

For those unfamiliar with the novel, Frankenstein is an epistolary tale, where the fantastical story is relayed via a ship’s captain, Walton, writing to his sister Margaret back in England. The 1994 film retains Walton and the North Pole setting, keeping faith with the crew’s encounter firstly with a strange, unnatural man, and then with a stranded and seriously ill gentleman – Victor Frankenstein, who says he is pursuing the strange figure. They get him on board and he soon forms a friendship with Walton – another man of ambition, whose determination to pursue his voyage against terrific odds leads Victor to tell him his cautionary tale. Taking in his early years, his studies in Ingolstadt and his subsequent successes in the field of human biology, Victor’s greatest achievement would be his downfall. Whilst his description of his method is scanty, he acknowledges that he makes a man out of salvaged body parts – the spoils of the charnel house and the dissecting room. When the unnamed creature awakens, Victor flees in terror.

He finally returns to his lodgings and the creature is gone; assuming it will have crawled away and died somewhere, he rather naively dismantles his scientific apparatus and hopes the whole thing was something of a nightmare. Instead, the creature survives, holes up in a shack alongside a cottage in the woods, and begins to learn from the inhabitants. As the creature learns language, he learns about man’s cruelty, and man’s hatred of any being so malformed as he. Learning of his creator’s name from the journal he blindly stole from Victor’s lodgings, as well as learning of Victor’s horror at what he has created, the creature vows to seek him out, satiating his rage on members of Victor’s family and inner circle, before finding Victor himself and demanding that he makes him a female companion so that he may absent himself from the world of men for good. Victor initially agrees, but at the last possible moment, reneges: the creature therefore avenges himself in the most brutal manner, and Victor, now bereft of his family and his wife, chases him North. An artful game of pursuit ensues, one which ends in the frozen wastes, where Walton finally encounters Victor.

“The accomplishment of my toils…”

The vast majority of adaptations of Frankenstein dispose altogether with the framing narrative and concentrate on the story of Victor Frankenstein and his creation. It is heartening that Branagh and screenwriter Steph Lady retain the section of the story which takes place in the frozen North, as there is lots of subtle horror to be inferred from the isolation of this extreme environment; it also provides a justification for Victor’s narrative, as he would presumably never have shared this tale unless he wanted to warn his new friend of the perils of ambition. I would quibble over the creature’s early cruel behaviour (to the sled dogs) as this doesn’t necessarily chime with his character overall, but I can see that it allows him to be viewed as potentially incredibly destructive, which is relevant. The stage is then set for the more typical examination of Victor Frankenstein’s life and loves, which comes via a superb cast and care and attention to details of setting that are of great importance. The backdrop of the Alps, for example, is an important contextual point, offering natural beauty and perilous enormity in equal measure, reflecting character moods and dispositions and also, the location of Victor’s first meeting with his now lucid creature. It’s heartening that this is retained; it couldn’t really be ‘Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’ without this nod to the dynamics of Romanticism, which influenced her so profoundly.

Other key strengths in this version could in some respects be seen as a little clumsy, but in the limited time available to flesh out the story on screen, they still work. For example, having Caroline Frankenstein – Victor’s mother – dying in childbirth, rather than of scarlet fever, does at least allow the film to establish Victor’s warped obsession with birth and death, a visual cue for a plot point which is even a little obtuse in the novel. The frequent allusions to some future wedding-night for Victor and Elizabeth are equally a little blunt, but given that the wedding-night scene is this film’s chief deviation from the novel, and contains several of the more horrific elements in the film, then evidently it was felt that the audience had to be prepped for its conclusion.

“…The tremendous secrets of the human frame…”

When films adapt Frankenstein, in so doing they often devote a large share of the screen time to the ‘science’ of the creature’s ‘birth’, and the style and focus of these scenes often tells us a great deal about the era in which the film is being made – our own mores always have an impact on what science, and how, we get to see, which inevitably however involves lightning (something never mentioned in the novel, although the development of galvanism, a new understanding of the relationship between electricity and muscle stimulation, was certainly an influence on Mary Shelley). In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the ‘birth’ scene is both interestingly novel and frustratingly formulaic, with a few curious details that don’t quite work.

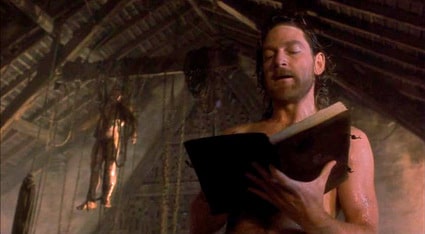

Rather than simply have Victor piecing together a man from component parts, Branagh links back to the trauma of childbirth (particularly given his mother’s grisly demise) by showing us Victor collecting amniotic fluid; it is this substance that he uses to immerse the creature, connecting birth and science here in a very literal way. This is an interesting enough motif, but then the film still goes ahead with the whole lightning shebang, emulating films which had gone before it, right down to the “It’s alive!” line, which has by now become a complete cliche. Homage? Possibly so, but it seems strange to dip back into Universal horror tropes when making ‘Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’. In other respects, the film definitely feels like it belongs to the world of the novel. The body parts ‘gathering scenes’, where parts were often taken from hanged criminals (a change in the law meant that practitioners of human dissection could claim criminal remains for their experiments, a fact which struck terror into the hearts of the general population – and was meant to) work pretty well; the decision to take materials from people known to him underlines Victor’s blind passion for his project, at least, even if there is no intimation of this in the book; the creature himself (played very ably by Robert De Niro) looks original, and very disturbing. Why Victor works so hard to revive the creature and then grieves momentarily when he seems to die is a strange choice, as surely it is Victor’s success that appals him – but otherwise, the creature’s birth has a reasonably strong impact overall. Much as it seems unlikely that an egotist like Victor Frankenstein would work alongside someone senior in years and expertise on a project such as this – and also his isolation in it drives much of the story – there is therefore a startling choice to be made when his partner is killed, which adds to the film’s much-needed horror.

For me though, however many minor gripes I find with the film, possibly its greatest strength is its inclusion of the De Lacey family – the impoverished inhabitants of the woodland cottage where the creature initially finds himself and hides. Watching him slowly begin to learn speech, and via language, self-awareness, is very compelling. The creature’s initial profound goodness in the face of horrifying human cruelty never fails to move me, and when he is driven out of the cottage after his hope of acceptance is so brutally snuffed out, weeping like a child in his isolation, you can understand perfectly why he turns his face from the goodness he knows he has. It is a harrowing, upsetting scene. In a film which has boundless overacting in several places (why speak quietly when you can just shout character names across the set?) De Niro provides the film’s greatest performance. He is plausible, pitiable and very human, ironically enough for a character who bewails his differences from mankind. Deviations from this level of tender detail harm the film, inevitably. Making Victor Frankenstein a bit sexy is needless (for example, having Justine Moritz look upon him as a love interest?!) but De Niro, for me, saves the day. The quieter moments in the film are the best it has to offer, too.

“I keep my promises…”

We have looked at some of the film’s key deviations from its source material, and so we come to the greatest deviation of them all – the wedding-night scene. And, although it plays fast and loose with the novel, I still feel it’s quite a clever move overall. In the novel, Victor, unable to interpret the creature’s threat that ‘I will be with you on your wedding-night’ as anything other than a threat against him (see? egotist) spends the early part of the evening on watch for the creature’s inevitable attack. The creature instead gains access to the bedchamber, where Elizabeth, Victor’s new bride, is waiting for him. He then strangles her, thus avenging himself on Victor by killing the person he loves the most. Grief thereby compels Victor to pursue the creature, hoping weakly for revenge.

In the 1994 film, the creature also murders Elizabeth – but the horror ante is upped by having him plunge his hand into her chest, ripping out her heart, just as Victor enters the room. In his desperation, Victor now sets about reanimating Elizabeth – she becomes the de facto Bride of Frankenstein, mutilated and partly burned by a fall into her bedside candle, making for an impressive set of make-up effects and a truly striking female creature. Rather than the anonymous female creature which Victor makes in Orkney in the novel, destroying her when he sees the creature looking on expectantly through the window, here we have all sorts of potential for deeper questions to be explored – will Elizabeth remember Victor? Love him still? Or will her awareness of her new state compel her towards the creature, with whom she has ghastly common ground? Helena Bonham Carter – who is also compelled to shout a lot during the course of the film, when she can do rather better than that – manages to communicate great anguish and hurt during her few moments as a reanimate corpse, and she does it all without recourse to language. Also, Victor’s blindness to her new, monstrous appearance shows how far gone he is by this point – willing to compete for her attentions with the creature, who of course believes her beautiful, because she resembles him. This sequence allows the film to repeat an earlier scene – where Victor and Elizabeth dance, whilst the camera circles them. Now when they dance, the camera circling them again, it is as a mockery of the past; Elizabeth is dead, Victor is too far gone to ever belong to society again, and the creature even appears to have the upper hand for a moment – before Elizabeth opts out of her grotesque situation, burning herself alive rather than belong to either of them. It’s the first real agency she’s able to display, and it makes for a thrilling, very dramatic plot point.

So could the film have stuck to the novel’s version, and conjured such a dramatic sequence out of the undoubtedly violent, but rather briefer way in which Elizabeth departs proceedings there? I don’t think it could. It’s a bold shift in many ways, not to mention a gamble, but it pays off. It’s also economical – dispensing with the protracted part of the novel where Victor and his friend Clerval tour around mainland Europe and Britain until Victor finds a suitably isolated spot to make a female creature. The revised version keeps things far closer to home, without dispensing with the important plot point that is the female creature.

Hideous Progeny

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) was by no means the first on-screen adaptation of the novel, and it certainly hasn’t been the last: numerous new films have emerged since its release, each of them utilising the source material differently. I imagine many more will follow, too, as this is a story which always seems malleable in times of crisis, reflecting and refracting our contemporary unease over whatever big questions of life and death trouble us currently. And, whilst the 1994 film is a film which begs many questions in terms of its method and manner, I still feel that its many strengths continue to make it worthwhile; it does stick closely to the novel in a number of ways, just as it claimed it would, and many of these ways contribute positively to the film, creating a sumptuous period piece which still looks very good today. Whilst some of its elements are bewildering, which is a shame, it is still a decent movie, one which perhaps deserves a re-visit, or even to find a new audience altogether as it enters its twenty-fifth year.