Hill House and Beyond

By Guest Contributor Matt Harries

For the first part of Matt’s special feature on Mike Flanagan, click here.

For Keri’s feature on The Haunting of Hill House, click here.

‘What struck me the most is that I think grief is such a universal experience that when we were in the writers’ room, every one of the writers at the table had their own perspective on it that came to bear with this, and that’s something that jumped out immediately that yeah, when you talk about ghosts and you talk about what gothic horror can do, this is an incredible opportunity to really lean face first into some of the saddest and darkest things that we all deal with.’ (Mike Flanagan on The Haunting Of Hill House).

If Mike Flanagan’s output since 2011 helped to establish a certain template – reverence for classic literary horror, preoccupation with family and the after-effects of trauma – then landing the adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s classic The Haunting Of Hill House on Netflix would provide the team at Flanagan Films the perfect opportunity to expand upon those themes which had become so central to their oeuvre.

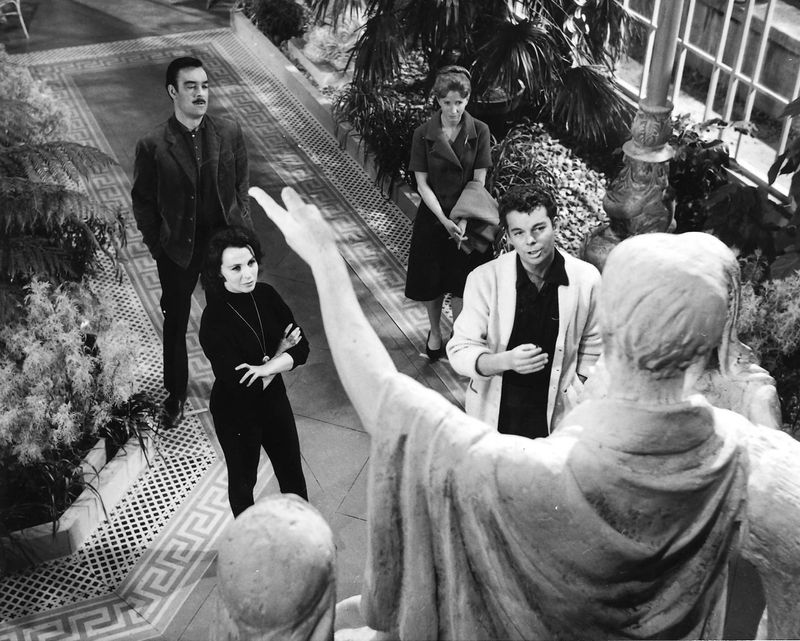

Apart from the challenge of expanding a novel into a television series, in fact Jackson’s 1959 gothic horror novel had already been the subject of two adaptations. The first, Robert Wise’s 1963 The Haunting, was broadly well-received by critics and despite a modest box office showing has long been highly-regarded by the likes of Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, while Wise also received a Golden Globe nomination for his directorial role.

Spielberg and Stephen King actually joined forces in the early Nineties, in an attempt to remake the story under the name Red Rose, but despite working on the project for several years, it was mutually shelved due to creative differences between the two – King apparently wanting more horror and Spielberg more action. Toward the end of the decade came the 1999 remake of The Haunting, starring Liam Neeson and Catherine Zeta-Jones. This was poorly received by critics and audiences alike and was eventually lampooned in the Scary Movie franchise.

It was the Robert Wise version, though, that proved influential to Mike Flanagan and as such, presented the first hurdle in considering any retelling of his own. How could he improve upon what he regarded as ‘a near perfect’ adaptation? In the end it is his status as a fan, first and foremost, that most deeply informs his skills of reinterpretation. A genuine love for the material, cultivated since reading the novel as a young man and presumably viewing the Wise version in a similar time-frame, seems to have driven the decision to craft an original piece that not only offers the potential for contemporary mores but also preserves the purity of the original. Flanagan describes his take on the Hill House story as a ‘reverent remix.’ He takes a fan’s-eye view of his favourite scenes, themes, lines of prose and so on and expands upon these threads, weaving them into a new whole and extruding a new form from the raw material of the source text.

Having experienced similar pressures in the making of Stephen King’s Gerald’s Game, Flanagan chose to continue to work with a number of actors, as well as behind-the-scenes team members, with whom he had worked in the past. Describing the process of creating Hill House as the toughest assignment of his career to date, the reliance upon a family-like group seems to have encouraged a depth of approach that greatly assisted the expansion of the themes hinted at by Shirley Jackson.

The Crain family, like other families, are at once a collective entity and a group of individuals. They find their own paths in the world beyond Hill House, but for all that they have flown their nest in very different directions, so they are all ultimately linked by the shared experience of family. Hill House, as hungry for souls as the day matriarch Olivia fell into its hungry maw, is as patient in those dark woods as the inevitability of our own connections to family. Our shared histories and their intertwining roots lead deeper and deeper into the bedrock of the past, to drink from the dark forgotten depths where emotions and energies are drawn; waters that feed the constant blooming of future life. Not all of these waters are healthy in their nature though, and the poisonous taint of some of them seem to gather within the very walls of the old house.

Is the house less a malign entity than a conduit or receptacle for uncounted years of human fear and pain? Are the demons and insecurities that afflict those that dwell within its walls merely amplified by the place, or has it grown over the years like some vast parasite, feeding upon the tragedy and trauma that occurs beneath its roof? In the end humanity, exemplified here by the Crain family, must find a way to live with its shadow side. For to attempt to destroy this facet would be to attempt to destroy human nature itself, with its joys, loves and victories built upon countless strata of memory and emotion, passed from generation to generation. Our true family inheritance.

‘I was so taken with getting to spend time with Danny Torrance again. It touches on themes that are the most attractive to me, which are childhood trauma leading into adulthood, addiction, the breakdown of a family, and the after effects, decades later. It really speaks to a lot of my favourite stuff, so I was really, really fascinated by the possibility of being able to play in that world.’ (Mike Flanagan on the making of Doctor Sleep).

A year on from Hill House and if one thing is for certain, it is that the writers, actors, producers and many others that comprise Mike Flanagan’s creative family are embracing ever greater challenges in their efforts to bring truly relevant storytelling to an increasingly expectant audience. While he may have described his previous work as his toughest challenge to date it is very much a case of ‘that was then, this is now’ for Mike Flanagan. Already proven as someone equally brave and adept when it comes to adapting the work of luminaries such as Stephen King and Shirley Jackson, he has thrown himself into a new project which seeks to combine and update not only King’s work but also the unforgettable cinema of another legend – Stanley Kubrick.

Doctor Sleep, slated for an autumn of 2020 release, will act as an adaptation not only of King’s novel of the same name but also an intertwining of the two versions of The Shining that have become so revered in their respective fields. Rather than merely aiming to bring the Doctor Sleep story to the screen, the intention is to nod to Kubrick’s own reworking while being mindful of King’s specific vision. This of course, meant getting approval from not only King – an avowed fan of Flanagan’s previous adaptation of his work as well as Hill House – but also the Kubrick estate. Successfully sending his script to both parties for evaluation surpassed the Hill House production as the new zenith of Flanagan’s career to date, especially considering King’s well-established antipathy toward the Kubrick version. Therein lay, to quote Flanagan, ‘the source of every ulcer we’ve had for the last two years.’ Spinning plates of this magnitude – balancing not just the desire and vision of the original creators but the demands and hopes of the fans of both iterations – means the eyes of the world will be upon the finished piece in greater number than ever. Coupled with this is that the Kubrick version has attained virtual iconographic status in the nigh-on forty years since its release.

There aren’t too many cinematic releases that can claim such a presence within the collective consciousness. Ridley’s Scott’s Alien franchise comes to mind as a series of films defined by the source material to such an extent that latter day deviations from the ‘classic’ material resulted in much wailing and gnashing of teeth, despite the attempt to align the Alien mythology with the concerns of a contemporary audience. Will the Flanagan trademark of combining classic tropes with universal human themes act as the glue that binds the disparate elements together, or ultimately water down the visceral impact and teeth-grinding tension? Conversely will the efforts to both pay homage – the addition of numerous ‘Easter eggs’ has already been mooted – and satisfy a certain prerequisite for scares, both psychological and physical, overpower any humanist element woven into the narrative?

At this point, all we can do is wait and see, although industry murmurings seem positive and with Netflix announcing the ordering of another new series (Midnight Mass) from regular collaborators Mike Flanagan and Trevor Macy, the momentum seems set to gather for the foreseeable future. For those of us who have followed the works of Mike Flanagan and his collaborators and seen that is it possible to give an audience brain-rattling scares and deeper meaning at the same time, we will surely be hoping for the best for his new ventures. For by approaching horror as more than a mere fairground ride of jumps and frights that can be timed on a stopwatch and delivered to order, Flanagan and co have shown the potential to reinvigorate and re-purpose the genre for an ever-changing world.