By guest contributor Matt Harries

Back in 1979, the late John Hurt almost certainly had no inkling whatsoever of his coming place within cinematic history. In this brief role among many in a storied career, he acted out one of the silver screen’s most iconic deaths. The gruesome demise of Executive Officer Kane of the USCSS Nostromo undoubtedly left an indelible mark upon cinema as a whole, horror cinema in particular and likely anyone who has watched it since. With the release of Ridley Scott’s classic Alien, the arena of macabre storytelling moved into the stellar depths. Space horror was born.

40 years later, and while the number of ‘true’ space horrors remains rather small, mankind’s preoccupation with space exploration remains at the forefront of his greatest ambitions. Indeed now the talk is of returning man and woman to space once again, to the moon and eventually, beyond. The International Space Station has been in low orbit around the earth since 2000. Ever more we are looking toward the goal of expanding the human frontier. The likes of Elon Musk, all ambition, passion and undefinable otherness, think big and talk big regarding the possibilities of space exploration. Our farthest travelled spacecraft, Voyager 1, was launched just before Alien, in 1977. In the intervening years it has travelled some 13 billion miles into space – only human imagination has taken us further. For is it not upon the paths our most far fetched imaginings describe that the dreams of science are eventually realised?

Regarded from space, the earth stands out like an exotic jewel. Its colours of blue and green, swirling whites and greys, its stark, arid browns and yellows; together these colours speak the language of biological life, and as denizens of the earth it is our language, the language of our blood and of our bones. Our earth, rarest of gems among the cold stars, an impossible multitude of distant, scattered diamonds. The locus of our particular species, all we are; contained within a sphere that floats amidst an immensity so boundless we can only reach for it conceptually.

At times here on earth we see our world as both vast and crowded, beautiful and mundane, barren and verdant. Stunningly alive and at the same time, slowly dying. When we look back at from space, whether from a photograph taken on the surface of the moon, or an image beamed from a distant satellite, we are struck by a keen sense of our world’s relative insignificance, its rarity and fragility. It is surely a wonder we should ever dream of leaving.

We are often told by certain spiritualists that there is no true separation between ourselves and the universe. Yet who can truly suppose to know such a truth, to know it in their bones? The idea that we are one with faraway Pluto, with Saturn and its ringlets of ice and rock, with the vast swirling gaseous storms of Jupiter – yet alone with the unmapped, unknown and unseen that exists beyond our reckoning – this seems an almost counter-intuitive leap of the imagination. On the other hand, as we are creatures of the tides and forests and the soil; we feel this as an indivisible part of our connection with the world. Yet humanity greedily dreams of a life away from Mother Earth, away from the source of our physical bodies, the cradle of life. How can it be that we feel somehow constrained here on this planet? How is it not enough to simply remain here, embracing our fate and the earth’s as one and the same? One thing that is certain is that we have been dreaming of travelling beyond our solar system and expressing this desire through our imaginations, for uncounted generations.

In 2019 we seem, perhaps more than ever before, to be living in the shadow of imminent dystopic predictions. Climate change, global economic instability, famine, war, mass migration. The sixth extinction. The Anthropocene era. These are some of the pressures that, as described by many a science fiction yarn, will eventually drive humanity forward on its quest to leave the earth and populate the solar system and beyond. While visionaries such as Musk bend their considerable intellect and wealth upon this goal, imbuing their efforts with a narrative of humankind’s growth, expansion and achievement, science fiction continues to offer an altogether more cautionary parallel narrative. One that seeks to examine the implications of what happens when we reach beyond the protection of Gaia, placing ourselves into the very maw of a godless, sometimes malicious, universe.

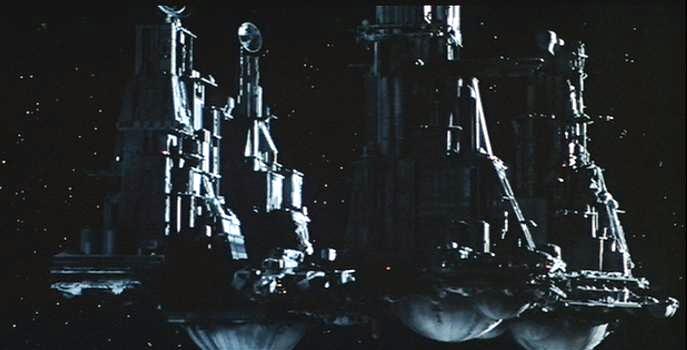

Reclassified as a distinct entity by virtue of its extraterrestrial setting, fundamentally space horror is a cinema defined by location; usually a vast spacecraft capable of interstellar travel. The action may move at times on to a planetary body or perhaps into the void of space itself, but is aboard these vessels where much of space horror’s defining tropes take their dreadful shape. The quintessential mother ship, whether the Nostromo in Alien, the Event Horizon, or the Elysium in Pandorum, is at turns labyrinthine, vast, monolithic and claustrophobic. Both sanctuary and tomb. Nothing reinforces mankind’s precariousness quite like the voyages that take us into deep space, for the invisible cord that connects all living things on earth is stretched thinner and thinner, until it no longer tethers. Beyond the reach of human agency, these often sentient world-structures designed by man can take on sinister new aspects, as if they no longer need to obey the whims of the small fleshy creatures who walk their tunnels.

In Alien, the ship’s computer, MU/TH/UR was always aligned with the mission of Ash, the rogue science officer played by Ian Holm, for whom preservation of the xenomorph sample was the prime objective. In Event Horizon, the eponymous ship ‘returns’ from travels beyond human reckoning with what seems to be the intention to journey back to this realm of ‘pure chaos’ carrying a fresh human cargo. In Pandorum, the Elysium, over the course of its massively elongated mission lifespan, becomes far less a haven than a miniature hell, within which humanity mutates into something altogether monstrous.

Whether it is the spacecrafts that are our homes, the artificial intelligences designed to protect us and act in our best interests, or, various memorable turns such as Sam Neill’s maniacal leading scientist Dr William Weir or Guy Pierce’s billionaire entrepreneur of the Alien mythology; humanity’s intentions in space horror are rarely reflected in the outcomes of our actions. The examples of the failure of human intention are many and varied. Time and again, we confidently assert our might against the barely understood horrors of the universe. Our strongest warriors are defeated by the savage defiance of unearthly creatures. Our most advanced technologies are rendered unusable or unsuitable, their purpose and function usurped. Our greed for material wealth, for advantage in warfare or empire building – how swiftly these ambitions, that are unchecked upon our own terms, leave us hapless as mice before the hawk when we stray too far.

Perhaps our greatest strength as a species is our sheer curiosity, our hunger to fathom the darkest depths and overcome what seem like the boundaries of our condition. To ceaselessly redefine them, moving beyond them and integrating them into our sense of who we are. To make clear who we must become if we are to move beyond our status quo. Mankind, the restless wanderer, whose desires and dreams are too great to let his very home in the universe confine him. Where will this ceaseless pushing get us in the end? In 1979 Ridley Scott’s Alien demonstrated that for all we believe ourselves equipped to tackle the challenges of deep space – for all the crew’s good intentions, or the guile and hunger behind the secret will that drives the true mission of the Nostromo – we are simply another creature wandering unawares, among unknown stars haunted by the unseen and unimagined forces of the universe.

In 1639 John Clarke, the headmaster of a Lincoln Grammar school, noted in his collection of proverbs Paroemiologia anglolatina, that ‘he that pryeth into every cloud may be struck by a thunderbolt.’ Perhaps though, it is fitting we leave the final word to one of the film’s taglines, quoting Science Officer Ash;

“The perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility…its purity. A survivor – unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.” …Is there room enough in space for us and it?