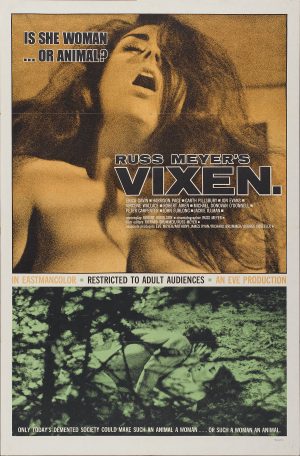

Fifty years ago this week, the 16th feature film from American writer-director Russ Meyer – and the very first US production to be given the X-rating – had its premiere screening. Although, as with Meyer’s entire body of work, Vixen is now generally classed as a cult film, it was on release an unprecedented commercial success, a major career turning point for the exploitation filmmaker, and arguably as significant a film as any in setting the stage for the more permissive, confrontational and experimental American cinema of the decade that followed. Not a bad show for a director whose name will always first and foremost be synonymous with big tits.

Fifty years ago this week, the 16th feature film from American writer-director Russ Meyer – and the very first US production to be given the X-rating – had its premiere screening. Although, as with Meyer’s entire body of work, Vixen is now generally classed as a cult film, it was on release an unprecedented commercial success, a major career turning point for the exploitation filmmaker, and arguably as significant a film as any in setting the stage for the more permissive, confrontational and experimental American cinema of the decade that followed. Not a bad show for a director whose name will always first and foremost be synonymous with big tits.

Pin-up photographer and former World War II combat cameraman Meyer had come a long way since breaking through in film as the ‘King of the nudies’ with 1959’s The Immoral Mr Teas and a series of similar low-brow, largely plotless features notable for their abundance of large breasted women in states of undress. After taking a left turn into American Gothic (most famously on 1965’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!) then tackling a few comparatively sedate, much less interesting romantic melodramas, in 1968 the director “set about making what we thought would be the sexiest film that had ever been made. And there came Vixen!”*

Spoilers ahead.

Spoilers ahead.

Quite apart from serving as an apt summation of the title character, Vixen is also the given name of our protagonist, the wife of a busy bush pilot up in a remote region of rural Canada (although the film was in fact shot in Oregon). As she’s burdened with a voracious sexual appetite, and frequently left alone for extended periods of time, it may not come as much surprise that Vixen is always cheating on her seemingly oblivious husband. We meet her as she does the deed in the great outdoors with what turns out to be a Mountie. Not long thereafter we see she even goes so far as to flirt shamelessly with her own brother, biker boy Judd. Then hubbie Tom returns with guests in tow, an American husband and wife stopping off to sample the fishing and hiking for a couple of days – but of course, they’ll both sample a bit more of the local experience than that. Once this couple moves on, however, things take a bit of a darker, surprisingly political turn, as Tom’s latest client turns out to be a communist bent on hijacking their small plane and eloping to Cuba with Niles, Judd’s African-American biker buddy who fled to Canada to evade being drafted for the war in Vietnam.

Meyer himself credited much of Vixen’s success to the casting of Erica Gavin in the lead, and he wasn’t overstating the case. The director revelled in exploring his own sexual fantasies on film, and had an expressed interest in women who not only sported hourglass physiques and enormous mammary glands, but also aggressive, take-charge personalities. The most pointed example of this is, of course, Tura Satana’s Varla in Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, yet we see much of the same general persona in Vixen – only this time, it’s a drive, aggression and assertiveness rooted almost entirely in sexuality, without the homicidal tendencies. From the early moment when Vixen impatiently tears off her bikini top whilst berating her lover of the hour for taking too long to get to business, there’s no question of who wears the proverbial trousers (even if they get dropped soon enough) in her illicit liaisons. Considering that Meyer’s films might easily be considered the epitome of the male gaze – which, of course, figures heavily here, with the expected abundance of fetishistic breast shots – it’s worth noting how Vixen plays predominantly from its female protagonist’s point of view, and frequently emphasises the desire and pleasure on her face. This, Meyer argued, was key to the film winning over a wider audience than his earlier films, as Gavin appealed as much to women as men; as Anne Billson notes, Vixen was one of the first American sex movies which drew audiences of couples, as opposed to just the standard dirty raincoat brigade. The fact that Gavin’s physical proportions aren’t quite so astronomical as those of such other Meyer muses as Kitten Natividad, Uschi Digard and Raven Delacroix may well be another factor in making her that bit more relatable.

Yet while Vixen would seem to be a pathological nymphomaniac who takes sadistic delight in driving all the men around her to despair (as the tagline put it, ‘Is she woman… or animal?’), the film does not on the whole condemn her promiscuity. Sure, it revels in her lusty shamelessness, each successive sexual encounter pushing the envelope that bit further into taboo: first basic infidelity, then the seduction of a married man, then lesbianism, and finally even incest. Yet by stark contrast with most licentious leading ladies of earlier exploitation films – including the title character of Meyer’s own Lorna – Vixen is not sentenced to death for her sins. Certainly she suffers, and the final scenes indicate that she has grown as a person for the better; but, as is clearly indicated by her climactic smile to the camera, prompted by the arrival of a new guest couple (one half of which happens to be Meyer himself, getting a Hitchcock in), Vixen’s extra-marital sexual appetite remains unabated. More to the point, the film even suggests that her sexual openness can have a truly positive impact: her seduction of both the tourist fisherman Dave and his wife Janet (with actress Vincene Wallace obviously being as voluptuous and frequently nude as Gavin) appears to have helped rekindle the flame between the hitherto frustrated couple. In this, it’s not hard to see why Vixen was embraced by a culture moving toward greater sexual liberation.

Even so, a key part of why Meyer’s filmography remains so fascinating and perplexing to this day is how the films are never content to simply titillate, and always make a point of taking unexpected turns and throwing in all manner of odd incongruities. This is certainly the case in Vixen; even with Meyer’s proviso of making the sexiest film ever, he can’t help but slap on a hearty side order of alienating weirdness, from the opening title sequence and prologue which play out like an advertisement for the Canadian tourist board, to a number of unexpectedly bombastic music cues, and a plethora of surreal cutaways: take Vixen bathing in a daylight stream immediately before joining her husband in bed after dark, and Meyer’s signature shot up through the exposed springs of a temporarily invisible mattress.

Most jarring of all, though (and I don’t necessarily mean that as a negative), are Vixen’s overtly political elements. While for the most part the film’s sexual content shouldn’t raise too many eyebrows today, modern audiences would seem a great deal more likely to be shocked and appalled by much of Vixen’s dialogue in relation to Harrison Page’s Niles. Quite apart from her irrepressible lasciviousness, Vixen’s other most overt character trait is that she’s a virulent, outspoken racist, a side of her which comes out with every bit as much force as her sex drive when she and the young black man are in the vicinity of one another. Much as how the whys and wherefores of her sexual excesses are never the subject of any scrutiny, nor does the film ever attempt any explanation as to why Vixen is so hateful towards black people, yet there’s never any question that her prejudice is intended as a negative character trait. Given that the film went into production mere months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr, there can be little doubt that there’s some commentary on the civil rights era at work here. By the final act, Niles becomes every bit as pivotal a character as Vixen, as the Irish communist O’Bannion, recognising the anti-establishment spirit in this oppressed, disenfranchised draft-dodger, attempts to recruit him to the communist cause, and very nearly succeeds.

We can scarcely fail to mention that Niles’ near-conversion to communism comes in the immediate aftermath of his rape of Vixen. (Some accounts of the scene might say it’s only ‘near-rape,’ but I should hope we all know better than that these days.) Naturally this is the most unpleasant scene in the film, particularly as Gavin’s horror is played out in every bit as extroverted a manner as her passion in earlier scenes, and there’s a very unsavoury overtone to it all as the connotation seems to be that Niles is giving Vixen the punishment she deserves for her bigotry toward him. Furthermore, when the two make peace in the final scene – one of only two moments in which Vixen addresses Niles by his real name, as opposed to ‘Rufus’ or ‘Sambo’ (the other time being out of fear, immediately prior to the rape) – we might take this to imply that the rape was a necessary and cathartic art for both parties. As unpalatable as this suggestion might be in 2018, we have to bear in mind that the world was a different place in 1968, and that Meyer and other exploitation filmmakers of the time tended to consider it an obligation to throw in a hint of Old Testament-style judgement on their sinful protagonists to give the films more of a fighting chance among religious audiences. And, as we noted already, the film stops short of giving Vixen the ultimate punishment which so often befell characters of her ilk at the time, and indeed in years since (take Gavin’s tragic lesbian character in Meyer’s later film Beyond The Valley of the Dolls).

We can scarcely fail to mention that Niles’ near-conversion to communism comes in the immediate aftermath of his rape of Vixen. (Some accounts of the scene might say it’s only ‘near-rape,’ but I should hope we all know better than that these days.) Naturally this is the most unpleasant scene in the film, particularly as Gavin’s horror is played out in every bit as extroverted a manner as her passion in earlier scenes, and there’s a very unsavoury overtone to it all as the connotation seems to be that Niles is giving Vixen the punishment she deserves for her bigotry toward him. Furthermore, when the two make peace in the final scene – one of only two moments in which Vixen addresses Niles by his real name, as opposed to ‘Rufus’ or ‘Sambo’ (the other time being out of fear, immediately prior to the rape) – we might take this to imply that the rape was a necessary and cathartic art for both parties. As unpalatable as this suggestion might be in 2018, we have to bear in mind that the world was a different place in 1968, and that Meyer and other exploitation filmmakers of the time tended to consider it an obligation to throw in a hint of Old Testament-style judgement on their sinful protagonists to give the films more of a fighting chance among religious audiences. And, as we noted already, the film stops short of giving Vixen the ultimate punishment which so often befell characters of her ilk at the time, and indeed in years since (take Gavin’s tragic lesbian character in Meyer’s later film Beyond The Valley of the Dolls).

All things considered, Vixen’s reactionary undertones are easily outweighed by its progressive overtones – yet we shouldn’t ignore the fact that both are prominent in the film. With this in mind, Vixen might well be regarded one of Russ Meyer’s most personal works, most reflective of the director’s own personality: an unabashed voyeur and breast fetishist, yet also a man in genuine awe of powerful women; a forward-thinking free spirit almost accidentally in tune with the love generation, yet also a man of proud military heritage and a firmly conservative work ethic; a sex film pioneer who pushed the boundaries of taste and decency, yet always stopped short of hardcore pornography; an exploiter of women, whose films might nonetheless be considered feminist. Vixen embodies all these curious contradictions which keep us watching and discussing Meyer’s work all these decades later, and it was vital in setting the stage for the most outlandish and celebrated phase of the director’s career, from the studio heights of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, to the indie excess of Supervixens, Up, and Beneath the Valley of the Ultravixens. As mentioned, leading lady Erica Gavin would reunite with Meyer on Dolls (as would Harrison Page), but would enjoy no further big screen roles beyond 1974’s Caged Heat. A shame that such a talented performer should fall from the limelight so soon – but hey, if you’re only going to have a short acting career, appearing in two of Russ Meyer’s definitive films and the greatest American women in prison movie is a pretty damn good track record. And never forget that she, and Vixen, are a whole lot more than just a great rack.

* Quote from ‘Breast Man! A Conversation with Russ Meyer’ by Anne Billson