Everyone and their mums will tell you that the slasher genre came into being in the mid-1970s; building primarily on the legacy of Hitchcock’s Psycho, such down and dirty independent productions like Last House on the Left and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre laid the groundwork for the innumerable stab-happy B-movies which came in the wake of John Carpenter’s Halloween. Conventional wisdom also tends to point toward the slasher not only being a product of its time, but of its place: the subgenre seems uniquely American in a way that earlier, more Gothic horror formats do not.

Everyone and their mums will tell you that the slasher genre came into being in the mid-1970s; building primarily on the legacy of Hitchcock’s Psycho, such down and dirty independent productions like Last House on the Left and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre laid the groundwork for the innumerable stab-happy B-movies which came in the wake of John Carpenter’s Halloween. Conventional wisdom also tends to point toward the slasher not only being a product of its time, but of its place: the subgenre seems uniquely American in a way that earlier, more Gothic horror formats do not.

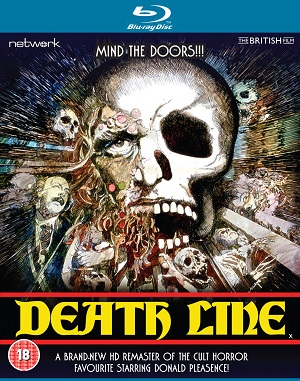

Of course, conventional wisdom is something we should always be wary of, for more often than not a little bit of digging can present a radically different picture. After all, whilst Psycho is oftentimes classed as the first slasher, this can also be argued of Michael Powell’s then-hugely controversial British shocker Peeping Tom, also made in 1960. On top of which, there are more than a few other British productions which came in the years ahead which clearly indicate the gradual evolution of the slasher format, many of which tend to be forgotten today: 1971 Hammer production Hands of the Ripper, 1972’s The Fiend (AKA Beware My Brethren) – and another 1972 production, Death Line, otherwise known as Raw Meat. Although, just to muddy the waters in the ‘Britain invented the slasher movie’ debate, Death Line was very much a transatlantic work: while made and shot in the UK with an almost entirely domestic cast and crew, it was produced by an uncredited Alan Ladd Jr (Hollywood bigwig whose CV would later include Police Academy, Braveheart and Gone Baby Gone), and was the first feature from Chicago-born director Gary Sherman (Dead and Buried, Poltergeist III).

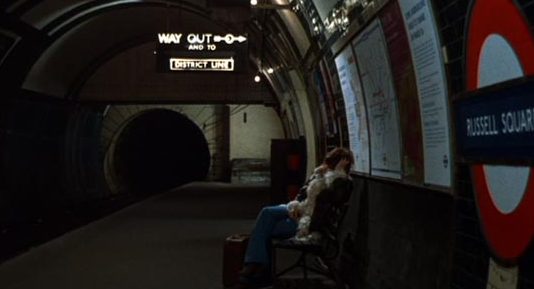

An ultra-sleazy atmosphere is established from the get-go, as we open to the sound of sordid synthesizers hammering out a stripperish rhythm, whilst the camera pulls in and out of focus on the lurid window displays in a succession of Soho night spots, all ‘girls girls girls’ and the like. We see an unidentified upper class gent in a suit, bowler hat and neat moustache strolling between said establishments, taking in the sights and clearly getting in the mood for a bit of how’s your father. Venturing down to the London Underground to get the tube, the good old boy’s evening takes a turn for the worse after a proposition to a suspected prostitute doesn’t go the way he hoped; but this turns out to be the least of his problems. Soon thereafter, university student Patricia (Sharon Gurney) and her American boyfriend Alex (David Ladd, half-brother of producer Alan Ladd Jr) get off the train on their way home to find this stranger lying unconscious on the stairs. While Alex would rather not get involved, Patricia insists they do something to help; but after they fetch a policeman, they return to the scene only to find the man has vanished. As the man in question turns out to be a well to-do civil servant and OBE, this makes the case a matter of great interest to local copper Inspector Calhoun (Donald Pleasance). But no one can begin to suspect the shocking truth: that there is a deformed, deranged, diseased man (Hugh Armstrong) living in a long-since abandoned tube station nearby, venturing out now and then in search of food, and human contact.

An ultra-sleazy atmosphere is established from the get-go, as we open to the sound of sordid synthesizers hammering out a stripperish rhythm, whilst the camera pulls in and out of focus on the lurid window displays in a succession of Soho night spots, all ‘girls girls girls’ and the like. We see an unidentified upper class gent in a suit, bowler hat and neat moustache strolling between said establishments, taking in the sights and clearly getting in the mood for a bit of how’s your father. Venturing down to the London Underground to get the tube, the good old boy’s evening takes a turn for the worse after a proposition to a suspected prostitute doesn’t go the way he hoped; but this turns out to be the least of his problems. Soon thereafter, university student Patricia (Sharon Gurney) and her American boyfriend Alex (David Ladd, half-brother of producer Alan Ladd Jr) get off the train on their way home to find this stranger lying unconscious on the stairs. While Alex would rather not get involved, Patricia insists they do something to help; but after they fetch a policeman, they return to the scene only to find the man has vanished. As the man in question turns out to be a well to-do civil servant and OBE, this makes the case a matter of great interest to local copper Inspector Calhoun (Donald Pleasance). But no one can begin to suspect the shocking truth: that there is a deformed, deranged, diseased man (Hugh Armstrong) living in a long-since abandoned tube station nearby, venturing out now and then in search of food, and human contact.

It’s quite an eye-opener that this film was in cinemas two years prior to Hooper’s TCM, and a full five years before Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes, as so many of the tropes we primarily identify with those films are in evidence here. Armstrong’s antagonist, credited only as ‘The Man,’ is a different kind of monster for a more socially conscious era; a casualty of industry, illness and class inequality, this latter point emphasised most pointedly by his first victim being an upper class twit. Beyond the political overtones, the Man and his methods are astonishingly gruesome for a UK production of the time: the pustulent sores that litter his face, the assorted literal skeletons in his closet, and the means by which he incapacitates any would-be threats are really quite repugnant to behold, and if we’re still gagging at it all in 2018, God knows how the general audience responded in 1972. However, there’s also a distinctly tragic element to the enigmatic figure, with echoes of Karloff’s misunderstood Frankenstein monster, and – in his one turn of phrase, “mind the doors” (presumably the words he has heard called most often living in the underground) – we might also detect some foreshadowing for one of the most tragic Game Of Thrones characters, Hodor.

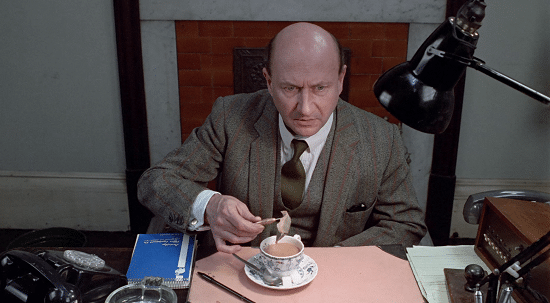

However, this is not to suggest that Death Line is nothing but downbeat, progressive horror emphasising misery and suffering above all else. Not unlike Last House, it’s a curiously schizophrenic affair, contrasting its grim content with some surprisingly goofy humour. The casting of Donald Pleasance is naturally a point of great interest in arguing Death Line’s importance in the genesis of the slasher, given that Pleasance went on to star in the most influential slasher of them all, but Inspector Calhoun is very far removed from Halloween’s Dr Loomis; a gor-blimey cockney copper with a floppy hat, an unquenchable thirst for tea and booze, and an odd fixation on darts; note the still above, in which for no readily apparent reason he uses a dart to remove a tea bag. Pleasance is absolutely hilarious in the role, and seems to be having a blast; there’s a wonderfully off-the-cuff quality to much of his line delivery that gives his scenes a semi-improvisational feel. (It’s also nice to see him share the screen with Christopher Lee, who makes a brief, largely insignificant but nonetheless memorable cameo appearance.) Almost makes one sad that, in so many of his horror roles, Pleasance was only allowed to be the straight-faced purveyor of exposition, with his comedic gifts too often left untapped. And God knows, Death Line’s above-ground scenes really need him to liven things up, as George Ladd and Sharon Gurney make for pretty flat, boring romantic leads, eye-catching Suzi Quatro hairstyles notwithstanding.

However, this is not to suggest that Death Line is nothing but downbeat, progressive horror emphasising misery and suffering above all else. Not unlike Last House, it’s a curiously schizophrenic affair, contrasting its grim content with some surprisingly goofy humour. The casting of Donald Pleasance is naturally a point of great interest in arguing Death Line’s importance in the genesis of the slasher, given that Pleasance went on to star in the most influential slasher of them all, but Inspector Calhoun is very far removed from Halloween’s Dr Loomis; a gor-blimey cockney copper with a floppy hat, an unquenchable thirst for tea and booze, and an odd fixation on darts; note the still above, in which for no readily apparent reason he uses a dart to remove a tea bag. Pleasance is absolutely hilarious in the role, and seems to be having a blast; there’s a wonderfully off-the-cuff quality to much of his line delivery that gives his scenes a semi-improvisational feel. (It’s also nice to see him share the screen with Christopher Lee, who makes a brief, largely insignificant but nonetheless memorable cameo appearance.) Almost makes one sad that, in so many of his horror roles, Pleasance was only allowed to be the straight-faced purveyor of exposition, with his comedic gifts too often left untapped. And God knows, Death Line’s above-ground scenes really need him to liven things up, as George Ladd and Sharon Gurney make for pretty flat, boring romantic leads, eye-catching Suzi Quatro hairstyles notwithstanding.

This new release from Network marks Death Line’s UK Blu-ray premiere, and the film looks and sounds great. Extras on the disc itself are minimal, but include a video interview with the late Hugh Armstrong, plus a trailer and stills. There’s also an accompanying booklet on the film written by Laura Mayne.

Death Line is out on Blu-ray on 27th August, from Network.