Paul Verhoeven’s first Hollywood production was in many respects a case of ‘start as you mean to go on.’ In line with the Dutch auteur’s later, more celebrated work – RoboCop, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Starship Troopers (let’s put Showgirls to one side just now, although there’s a lot to be said for that one) – Flesh + Blood is a film which, taken on face value, seems like a perfectly audience-friendly genre piece, in this case a historical swashbuckler/bodice-ripper, easily sold as a Conan-style adventure movie (the presence of Basil Poledouris on music duties probably helping a bit there). However, you don’t have to look too closely to see that the filmmaker and his cast and crew have a lot more in mind than simply ticking the boxes for an established crowd-pleaser, and while they provide plenty of what the audience paid to see (i.e. the two attributes of the title), they also do their utmost to push us out of our comfort zones with challenging ideas, nuanced characters, and more than the occasional moment of deep unpleasantness. On top of being Verhoeven’s entry point to English language filmmaking, Flesh + Blood might also be considered a key title on the CVs of its lead actors, Rutger Hauer and Jennifer Jason Leigh, helping cement them both as among the boldest performers of their respective generations. (They would of course also reunite the following year on cult classic The Hitcher.)

Paul Verhoeven’s first Hollywood production was in many respects a case of ‘start as you mean to go on.’ In line with the Dutch auteur’s later, more celebrated work – RoboCop, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Starship Troopers (let’s put Showgirls to one side just now, although there’s a lot to be said for that one) – Flesh + Blood is a film which, taken on face value, seems like a perfectly audience-friendly genre piece, in this case a historical swashbuckler/bodice-ripper, easily sold as a Conan-style adventure movie (the presence of Basil Poledouris on music duties probably helping a bit there). However, you don’t have to look too closely to see that the filmmaker and his cast and crew have a lot more in mind than simply ticking the boxes for an established crowd-pleaser, and while they provide plenty of what the audience paid to see (i.e. the two attributes of the title), they also do their utmost to push us out of our comfort zones with challenging ideas, nuanced characters, and more than the occasional moment of deep unpleasantness. On top of being Verhoeven’s entry point to English language filmmaking, Flesh + Blood might also be considered a key title on the CVs of its lead actors, Rutger Hauer and Jennifer Jason Leigh, helping cement them both as among the boldest performers of their respective generations. (They would of course also reunite the following year on cult classic The Hitcher.)

We open in medieval western Europe, as the ambitious nobleman Arnolfini (Fernando Hilbeck) leads his armed forces in an assault on a city. Of course, when we say Arnolfini ‘leads’ the attack, all we really mean is he’s paying the wages of those doing the dirty work, among them a band of vagabond soldiers of fortune including Martin (Hauer), Karsthans (Hauer’s old Blade Runner co-star Brion James), Orbec (Bruno Kirby), and the heavily pregnant Celine (Susan Tyrell). While they may be a lewd, ragtag, belligerent bunch living hand to mouth and revelling in the pleasures of the flesh with all and sundry, the mercenaries believe they fight with God on their side, with a Cardinal (Ronald Lacey) on hand to dish out the appropriate blessings before they commit atrocities in the name of Heaven. However, on this occasion the greater sinner might be Arnolfini. After promising the mercenaries 24 hours of freedom to plunder the city to their heart’s content, the noble lord has a change of heart once it’s clear the raid was a success and the commoners are unlikely to leave anything for him, hence he goes back on his word and orders the leader of his forces, Hawkwood (Jack Thompson), to force them out under threat of cannon fire; not a duty Hawkwood takes lightly, as these soldiers are his friends.

Unsurprisingly, this leaves Martin and company less than pleased, and following what they interpret as a sign from God, they plot their revenge by hijacking a caravan of Arnolfini’s goods. However, amongst all the wine, meat, gold and finery, they stumble on something of even greater value: the young noblewoman Agnes (Leigh), betrothed to Arnolfini’s son Steven (Tom Burlinson), a man of learning with no military experience. The lusty, amoral bunch think they’ve found a new plaything, but the seemingly demure convent schoolgirl proves a bit more adept at surviving in this harsh new world than expected, and forms a close bond with Martin which throws off the balance of the group. In the meantime, the well-meaning Steven has not given up on his bride-to-be, and utilises his knowledge of the burgeoning sciences in a bid to rescue Agnes.

Unsurprisingly, this leaves Martin and company less than pleased, and following what they interpret as a sign from God, they plot their revenge by hijacking a caravan of Arnolfini’s goods. However, amongst all the wine, meat, gold and finery, they stumble on something of even greater value: the young noblewoman Agnes (Leigh), betrothed to Arnolfini’s son Steven (Tom Burlinson), a man of learning with no military experience. The lusty, amoral bunch think they’ve found a new plaything, but the seemingly demure convent schoolgirl proves a bit more adept at surviving in this harsh new world than expected, and forms a close bond with Martin which throws off the balance of the group. In the meantime, the well-meaning Steven has not given up on his bride-to-be, and utilises his knowledge of the burgeoning sciences in a bid to rescue Agnes.

In this Game of Thrones era, we’re a little more accustomed to old timey tales of warriors and maidens with a great deal more psychological depth and cruelty than your standard swashbuckler, but it’s not hard to envisage this approach backfiring back in the mid-80s when the sword and sorcery genre was at its peak. Small wonder, then, that Flesh + Blood wasn’t a box office hit, nor did it go down that well with critics. Verhoeven himself expresses some regrets about the film in the extras on this disc, in part down to on-set struggles with his international cast and crew (most notably Hauer, who had been the director’s go-to leading man of choice in the years prior, but has never worked with him again since). The director also laments concessions made for studio Orion Pictures, as the original story that he and screenwriter Gerard Soetman (another long-time collaborator of Verhoeven, who since reunited with the director on 2006’s Black Book) was quite far removed from what wound up on screen, and would have centred on the relationship between Hauer’s Martin and his former friend, Jack Thompson’s Hawkwood. However, Verhoeven and Soetman bent to the will of Orion, who insisted the ‘love triangle’ – yes, I’m using inverted commas on purpose – between Martin, Agnes and Steven should be the focal point. While it may seem surprising that Agnes was not always co-lead given how pivotal she is to the final film, there are indications that this might not always have been the case; for one, Agnes doesn’t first appear until more than half an hour in, before which time Martin’s interactions with both Hawkwood and Steven are given more significance.

Yet whilst Agnes might not have been intended as so central a character, she proves to be a compelling female lead, thanks in no small part to the casting of Jennifer Jason Leigh; it’s all too easy to imagine a lesser actress landing the role based on her looks and willingness to strip rather than actual talent, and messing the whole thing up (weird mental tangent: what if a young Jennifer Jason Leigh, or an actress of that calibre, had wound up playing Nomi in Showgirls…?) If you’ll pardon me bringing up Game of Thrones again, we might easily deem Agnes a forebear for Daenerys Targaryen (George RR Martin’s first novel didn’t show up until 11 years later, after all), as both characters initially seem to be helpless little princesses thrown to the wolves, yet prove to be considerably more cunning, powerful and manipulative than we might have anticipated. And of course, not unlike Daenerys, Agnes is forced to use her wits to survive after enduring rape. The sequence in question unsurprisingly ran afoul of the censors on release, but is presented uncut here, and it is of course an unpleasant spectacle which many modern viewers might deem ‘problematic,’ particularly as a romance of sorts ensues with Martin. However, it is very much left open to question what Agnes’s true feelings are, and whether she is simply doing what she must to survive.

Deception – including self-deception – is one of the key recurring themes of Flesh + Blood, and beyond the not-love story this is most pointedly explored via another of Verhoeven’s favourite subjects, Christianity. The film deals heavily with the hypocrisy of wars waged in the name of God, with Hauer’s Martin exploiting the faith of his fellow mercenaries to elevate himself to an almost messianic level, whilst they excuse their every act of barbarity and hedonism as ‘God’s will,’ Lacey’s Cardinal very much included. Verhoeven has long been noted for his use of imagery evoking Christ, and we have plenty of these here, both in Hauer’s rise to psuedo-saviour, and in moments of sadistic violence reminiscent of the crucifixion. Hand in hand with this, such moments also point toward many of Verhoeven’s most celebrated moments from his later body of work, perhaps most notably the murder of Murphy in RoboCop. In addition, the representation of more-or-less gender neutral warfare, men and women battling side by side, was an idea Verhoeven explored further in both RoboCop and Starship Troopers.

Deception – including self-deception – is one of the key recurring themes of Flesh + Blood, and beyond the not-love story this is most pointedly explored via another of Verhoeven’s favourite subjects, Christianity. The film deals heavily with the hypocrisy of wars waged in the name of God, with Hauer’s Martin exploiting the faith of his fellow mercenaries to elevate himself to an almost messianic level, whilst they excuse their every act of barbarity and hedonism as ‘God’s will,’ Lacey’s Cardinal very much included. Verhoeven has long been noted for his use of imagery evoking Christ, and we have plenty of these here, both in Hauer’s rise to psuedo-saviour, and in moments of sadistic violence reminiscent of the crucifixion. Hand in hand with this, such moments also point toward many of Verhoeven’s most celebrated moments from his later body of work, perhaps most notably the murder of Murphy in RoboCop. In addition, the representation of more-or-less gender neutral warfare, men and women battling side by side, was an idea Verhoeven explored further in both RoboCop and Starship Troopers.

It’s unfortunate that Flesh + Blood proved to be Verhoeven and Hauer’s last collaboration: the director explains in the extras that they fell out during production, as the actor – already well established in Hollywood after Blade Runner, Nighthawks and Ladyhawke – did the film primarily out of loyalty to Verhoeven, and felt it was a step backwards in his career. However, much as it’s hard to imagine Agnes being as commanding a presence without Leigh in the role, a lesser actor than Hauer might also have struggled to make Martin so compelling. He might be presented as the hero of the piece, but it’s clear that there’s a lot more to the role than that; while he is not without his admirable qualities, there’s a hell of a lot about him that’s contemptible. This, perhaps above all else, is the overriding theme of Flesh + Blood: there are no heroes or villains, only people acting on their (pun intended) basic instincts, with even the most ostensibly decent of them – i.e. Hawkwood and Steven – still demonstrating their capacity for cruelty and selfishness at times. And at the risk of sounding like a broken record, it’s this shades of grey morality within a landscape where we’re more accustomed to clear-cut good guys and bad guys that makes the film feel quite the trailblazer for Game of Thrones.

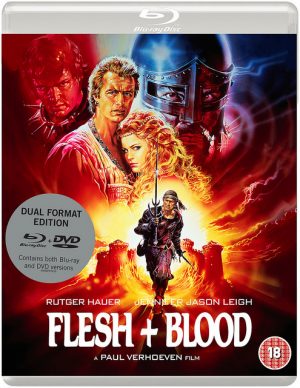

Verhoeven completists will definitely want to get hold of this new edition from Eureka, the first time Flesh + Blood has appeared on Blu-ray in Britain. Extras include a feature commentary from Verhoeven, a 2013 interview with the director, 2016 documentary Verhoeven on Verhoeven (slightly trimmed due to rights issues over footage from certain films), plus interviews with writer Gerard Soetman and late composer Basil Pouledoris and an audio interview with Hauer. The first pressing also includes a collector’s booklet.

Flesh + Blood is out on dual format DVD and Blu-ray on 6th August, from Eureka Home Entertainment.