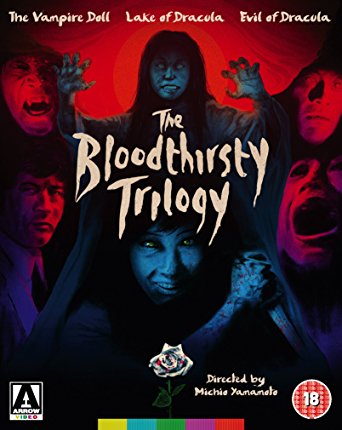

Inspired by the success of Hammer’s lurid horror cinema in the 1960s, the ever-versatile Toho Studios made a sound business decision to make some vampire films of their own. Whilst there is a modest array of films based specifically on Far Eastern vampire lore, the productions overseen by director Michio Yamamoto are rather different, blending Western tropes with a decidedly more Japanese spin on the folklore. The resulting projects, on offer here as part of one package released by Arrow Films, are an aesthetically-pleasing blend of whimsy and clever ideas, and would certainly be of interest to anyone with a fancy for seeing how world cinema does it.

Inspired by the success of Hammer’s lurid horror cinema in the 1960s, the ever-versatile Toho Studios made a sound business decision to make some vampire films of their own. Whilst there is a modest array of films based specifically on Far Eastern vampire lore, the productions overseen by director Michio Yamamoto are rather different, blending Western tropes with a decidedly more Japanese spin on the folklore. The resulting projects, on offer here as part of one package released by Arrow Films, are an aesthetically-pleasing blend of whimsy and clever ideas, and would certainly be of interest to anyone with a fancy for seeing how world cinema does it.

Happily, Japan can do Gothic; it has its own windswept, desolate roads and even remote mansions built in the once-stylish Western mode. In The Vampire Doll (1970), a young man, Sagawa, is on his way to visit his girlfriend Yuko in one of said mansions – a curious place, where kimonos and gilded frames somehow share the same shots. However, upon his arrival he’s told by Yuko’s kimono-wearing mother that, since Sagawa’s last communication with his beloved, she has passed away. Sad and shocked, Sagawa is invited to spend the night: it’s hopefully not too much of a spoiler to say here that the house is not all it seems…and shortly afterwards, Sagawa’s worried sister and her boyfriend are on his trail, so they make their own way to the mansion, where they must try to work out what’s going on.

In Lake of Dracula, made a little later (1971), there’s an additional sense of confidence on display, as showcased by the musical score as well as more and more appreciation for Japan’s landscapes, which seem more prominent here. There are also some stupendous settings: the deserted house, although it predates the latter, reminded me strongly of John Badham’s Dracula (which is high praise from me) and shows us that the Gothic horror staple of the creepy (Western) manor house is an integral part of this horror. This film follows the fate of Akiko, who had a very creepy dream as a child that she followed her dog into – you’ve guessed it – a dilapidated stately home, where she encountered a vampire. However, as an adult, she is made to doubt that it was a dream after all when a coffin is delivered to a friend of hers. At first the coffin contains…something, but after her friend returns from lodging a complaint with the delivery company, it’s empty, and the friend, Kusaku, is in trouble. Vampirism has arrived, aided and abetted before long by Kusaku (now operating as a kind of Renfield character) and it gradually closes in on Akiko – though the links to the most famous Dracula mentioned in the film’s title are spurious to say the least.

Finally, the third to be filmed (though second to be released) is Evil of Dracula: it’s not the most thought-provoking title, and this is perhaps the weakest of the films on the whole – though, if you enjoyed Shin Kishida as the vampire in Lake of Dracula, then you might enjoy seeing him doing a little more than playing a monster here. On the contrary, he’s gone and got himself a job by this point, working as a Principal in a girls’ school. When new teacher Shiraki arrives to take his post, he’s nonplussed by his oddball colleagues – and the small cohort of students who seem to be particularly unfortunate with mortality figures. After seeing more than he can feasibly declare ‘a bad dream’, Shiraki joins forces with the local doctor/folklore expert who tells him that there’s been something odd going on in these parts for some time…

The plot formulas are pretty standard, all told, and don’t look all that much written down, so perhaps it’s best to focus on the quirks and many positives on offer here. Aesthetically, The Vampire Doll probably boasts some of the most effective scenes, with Yoko in particular doing a star turn as both frail and frightening, although The Lake of Dracula is no slouch, with some beautifully-framed scenes and innovative music of its own. There’s a bit of proto-splatter in these films too, which doubtlessly had an influence on Japanese filmmakers growing up at this time (I’d hazard a guess that Hisayasu Satô might have seen these) and where the films meld 70s-era clothes and technology with the more ‘timeless’ aspects of vampires, I’d say they do a better job than Hammer did when it tried to go contemporary in some of its later films. You might take issue with the gratuitous use of roll-necks, but I did not. The films are overall well-paced too – not abrupt and not languid, allowing a pleasing atmosphere to develop, even if what you’re seeing unfold feels somehow familiar to you.

In terms of the cultural melding of East and West, there are some aspects of this to ponder, as well as interesting rationales for the emergence of vampires which are interesting, looking quite different to those in European films (but with similarities too: vampire women love a nice white gown). I rather like the golden eyes which the vampire characters have, too, even if you can’t help but wonder if they ran with that idea once they’d thought of it. However, I don’t think there are massively poignant cultural messages here, not really; there is an explanation in Evil of Dracula for how said count’s influence made its way to Japan, but the Japanese always seem rather relaxed about this kind of detail, and whilst you could ponder the presence of Western houses etc. as having more to say, equally you could just enjoy the spectacle on offer. If there’s one thing I found particularly interesting, it’s the use of hypnotism in the films’ plots; the development of this theme has a lot more in common with Poe than Mesmer himself, and it makes for some interesting denouements.

In terms of the cultural melding of East and West, there are some aspects of this to ponder, as well as interesting rationales for the emergence of vampires which are interesting, looking quite different to those in European films (but with similarities too: vampire women love a nice white gown). I rather like the golden eyes which the vampire characters have, too, even if you can’t help but wonder if they ran with that idea once they’d thought of it. However, I don’t think there are massively poignant cultural messages here, not really; there is an explanation in Evil of Dracula for how said count’s influence made its way to Japan, but the Japanese always seem rather relaxed about this kind of detail, and whilst you could ponder the presence of Western houses etc. as having more to say, equally you could just enjoy the spectacle on offer. If there’s one thing I found particularly interesting, it’s the use of hypnotism in the films’ plots; the development of this theme has a lot more in common with Poe than Mesmer himself, and it makes for some interesting denouements.

This being Arrow, they have as ever lined up an array of decent extras on The Bloodthirsty Trilogy, which by the way looks phenomenal on Blu-ray; I looked at some of the trailers on Youtube ahead of time, and the difference between the old prints and this new one is vast. Kim Newman offers his take on the films in a new appraisal, there’s an array of stills and trailers, reversible sleeve art, and if you get the first pressing you get some new writing by Japanese film expert Jasper Sharp in a special collector’s booklet. Essentially, I say this every time I review an Arrow package, but as this is their way of keeping physical releasing alive, then they deserve this kind of regular appreciation.

The Bloodthirsty Trilogy is available now from Arrow Films. For more information, click here.