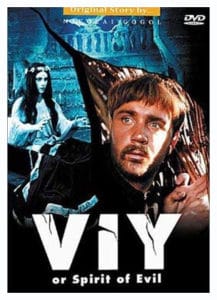

I’ve always thought it’s a crying shame that we generally know very little about Russian cinema; although many fine examples have made it across to the West, we can be sure that many have not, and even those which have are often very under-appreciated. And so it is that it has taken me around a decade from the point of seeing some intriguing stills in print from Viy (1967) to actually seeing the film itself. However, this omission has meant that I’ve just been able to see a film, which is now a staggering half a century old, as one amongst the most innovative supernatural yarns I’ve ever enjoyed to date. That is the magic of cinema. The best of it not only doesn’t have a best-before date; it actively gathers extra appeal from the intervening years, adding the charm of the time capsule effect to its other merits. Add Russian folklore into the mix and you also get that strange, but not displeasing distance, too – where the tales are similar, yet different; the predominant religion is unique, but also recognisable – and the threat of the otherworldly is so very Russian (or Ukrainian) in many ways, yet feels as though it’s interlaced with themes and ideas akin to many European stories.

The story starts at a seminary, not too distant from Kiev; the young clergymen who live there are being allowed to take a short break away, provided they return by a certain date. Now, I don’t know exactly how catholic priests behave at seminary, but these Eastern Orthodox lads don’t seem particularly pious, and are a raucous bunch. Three of them, including one Father Khoma (Leonid Kuravlyov, who is still acting) head off in great excitement for their vacation, but soon founder and get completely lost; rather than sleep in the wilds, they wander until they come across a farmhouse. The only inmate they discover is an old woman, thought she says they can stay – if they each sleep in separate areas of the house. Khoma settles in the barn, but is soon disturbed by the strange old woman, who menaces him before subduing him, climbing on his back, and treating him as a flying steed! Khoma is outraged by this violation of his dignity, and as soon as the witch lands, now miles from the farm, he beats her.

Mid-way through this beating, though, he happens to look down and sees that the old woman has somehow transformed into a beautiful young woman. She’s also by now badly hurt; Khoma, panic-stricken and horribly confused, flees the area, making his way back alone. He hopes that this is the end of the strange ordeal, but soon a conveyance arrives at the seminary, requesting his presence. It seems a local member of the gentry is about to lose his beloved daughter, who was recently mysteriously beaten and left for dead. She pleads with her father to take steps to save her soul, and specifically asks for Father Khoma to be sent to pray for her – hence, some of his workers have arrived to convey him there. He tries to wheedle out of it, but it is not to be. He’s packed into the wagon, and they head off to the village.

Alas, they’re too late. The young woman has already passed away, and her bereft father – whilst clearly curious as to why she would have kept silent on the identity of her attacker, as well as why she would have requested an apparently unknown priest to pray for her – is determined to keep his word to his child. Khoma is commanded to keep a church vigil over her remains for a period of three nights. if he achieves it, he’s promised a handsome reward. He’s worked out by this stage, of course, that the young lady is in league with the Devil – but can a dead girl really do anything to avenge herself on him?

The answer to this question makes for one of the most painterly, atmospheric tales I’ve yet seen unfold on screen. And it’s literally painterly, too – many of the backdrops are, as was common at the time, painted, providing the film with a picturesque look throughout. Here, you won’t find imposing castles or rain-swept vistas, like many equivalent European films being made at the time, and though these contemporary films were filled with lurid colours, Viy uses its own colours for different purposes. This film is full of working farm life (with lots of animals on set), villages and everyday buildings, whilst lots of believable rustics people the scenes as extras and curious, part-comedic characters, colourfully dressed, singing folk songs and adding light relief along the way – though all the characters are flawed, with Khoma clearly being the worst of them. When he’s not glugging the offered vodka, he’s fantasising about escape; he’s only successful in one of these pursuits. With these moments of brevity, the film’s humanity and its array of idyllic old-world charms, Viy often resembles a picture storybook. Adding to this effect is its bloodlessness; it never shows graphic violence on-screen. Death may be permeable here, as it is in so many folk tales, but the terror of the story derives from suggestion, not gore. I have to admit that based on the stills, and perhaps thinking of Hammer, I was expecting a vampire story here. The terror actually derives from something different from that.

The answer to this question makes for one of the most painterly, atmospheric tales I’ve yet seen unfold on screen. And it’s literally painterly, too – many of the backdrops are, as was common at the time, painted, providing the film with a picturesque look throughout. Here, you won’t find imposing castles or rain-swept vistas, like many equivalent European films being made at the time, and though these contemporary films were filled with lurid colours, Viy uses its own colours for different purposes. This film is full of working farm life (with lots of animals on set), villages and everyday buildings, whilst lots of believable rustics people the scenes as extras and curious, part-comedic characters, colourfully dressed, singing folk songs and adding light relief along the way – though all the characters are flawed, with Khoma clearly being the worst of them. When he’s not glugging the offered vodka, he’s fantasising about escape; he’s only successful in one of these pursuits. With these moments of brevity, the film’s humanity and its array of idyllic old-world charms, Viy often resembles a picture storybook. Adding to this effect is its bloodlessness; it never shows graphic violence on-screen. Death may be permeable here, as it is in so many folk tales, but the terror of the story derives from suggestion, not gore. I have to admit that based on the stills, and perhaps thinking of Hammer, I was expecting a vampire story here. The terror actually derives from something different from that.

This terror – Khoma’s ordeal – is handled with such skill that it only beggars belief that directors Konstantin Yershov and Georgy Kropachyov aren’t better-known for their work here. Rotating cameras, deft super-imposition and fantastic flying shots culminate in an end sequence which must be amongst the best of the era. I feel like I want to hold back on the detail; it’s far better to see for yourself, and perhaps to appreciate that ingenuity so often comes from restriction – as in, shooting in a time long before computer effects took over as the de facto method of making the magic happen meant creative solutions to showing an audience extraordinary events (based on a short story by Nikolai Gogol, which itself used some folkloric influence). I was surprised and engaged by the end result.

Viy is a tale where human fallibility is thrust into a parallel world of magic and mischief, then brought to life on screen in a vivid, innovative way. It marries the subtle and the striking, and its story of witches, ghouls and monsters is quite unlike anything else I’ve seen.