By Guest Contributor Claire Waddingham

Claire discusses how British nuclear horror Threads is the most terrifying film ever made – especially from the perspective of a historian.

This week, I watched a film called Hot Tub Time Machine. I needed some mindless entertainment. And it was mindless. A group of men get in a hot tub and go back to 1986. Completely mindless. Except for a pretty funny cameo by Sebastian Stan as a self-important bully, who was proud to be a pro-Reaganite anti-Communist patriot with a fetish for beating up Soviets in the fiercely Anti-Russian Eighties – and this did make me laugh, because in 1986, I’m pretty sure someone like Stan’s character would have been considered by many to be part of the sensible majority, rather than a figure of ridicule. The Cold War was at a peak in the mid 80s, with international relations between the two superpowers highly tense. The result of this was a particularly rich strain of culture, with sci-fi producing some wonderful films that hinted at a forthcoming apocalypse. We had The Terminator, Robocop, and Aliens, all of which potrayed huge, nameless corporations bullying the little people, threatening them with total destruction. But none of these three films – excellently made as they are – frighten me. It’s a British film, made on a next to nothing budget and with virtually no professional actors, that does. It’s called Threads. It’s a gritty, neo-realist film. Written by Barry Hines, and directed by Mick Jackson, it’s one of the best films ever made.

Threads is genuinely terrifying. Made in 1984 – a little over thirty years ago – it was produced at a point where Ronald Reagan brazenly claimed that rather than Mutually Assured Destruction, he’d rather go for a nuclear target strategy, and that the world could survive a “limited” nuclear war in Europe. With Detente dead in the water after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the prospect of a nuclear apocalypse was rearing its head again. In the mid 1960s, the wonderful neo-documentary The War Game was banned on the grounds it could trigger mass suicides. After the BBC aired Threads, it was promptly put in a vault for over twenty years.

This Summer, I bought the DVD. This was for my job – I teach History, and one of the key modules for my exam groups is The Cold War. This June, when half of my class of sixteen year olds were out on work experience, the others politely asked if we could watch a film. I then decided that I really needed to show them Threads.

So, we all sat down, in my warm classroom, and I pressed play. After half an hour, they had all gone rather quiet. After ninety minutes, a couple looked rather green. Then they confessed. These teenagers, the Millennial Generation who sneer at the dated effects of The Exorcist and aren’t happy unless someone is decapitated in the first five seconds in the multiplex, were all terrified. Threads had shocked the unshockable generation.

Why were they so shocked? Because this film completely exposes the helplessness of humanity in the face of a nuclear armageddon. It reveals the fragility of civilisation. It opens with a delicately spun spider web – symbolising those threads, the bonds that hold society together. Then it pans out to a shot of Sheffield. Yes, Sheffield. Not glamorous London or bustling Manchester, but a Northern city that is remarkable for its unremarkableness. The skies are grey and overcast, and we open with a shot of a young couple in a Ford Cortina, discussing an unplanned pregnancy. It’s an ordinary, humdrum existence, where people are only concerned with their own issues. Suddenly, we are in a family drama. With the dull décor, the clothes, we could be watching a shoddy Coronation Street knock off. People go to the pub. Go to their jobs. Argue. It’s normal life. A normal life with running water, police, food supplies, schools, entertainment, communications. The life that everyone takes for granted.

Except there are constant news updates running through this. The threat of war. Invasions of Iran. The sinking of the USS Kittyhawk. And then the film veers into a dark, dangerous direction – the attempts of local government to prepare for nuclear war. The angry protests of the TUC and CND that warn of a “corpse” of a country, with poisoned water, dead livestock, useless soil, and a dying population. This is where it began to get frightening. What, this film asks, is the point of trying to survive a nuclear war? What is the point of paying attention to the Protect and Survive leaflets?

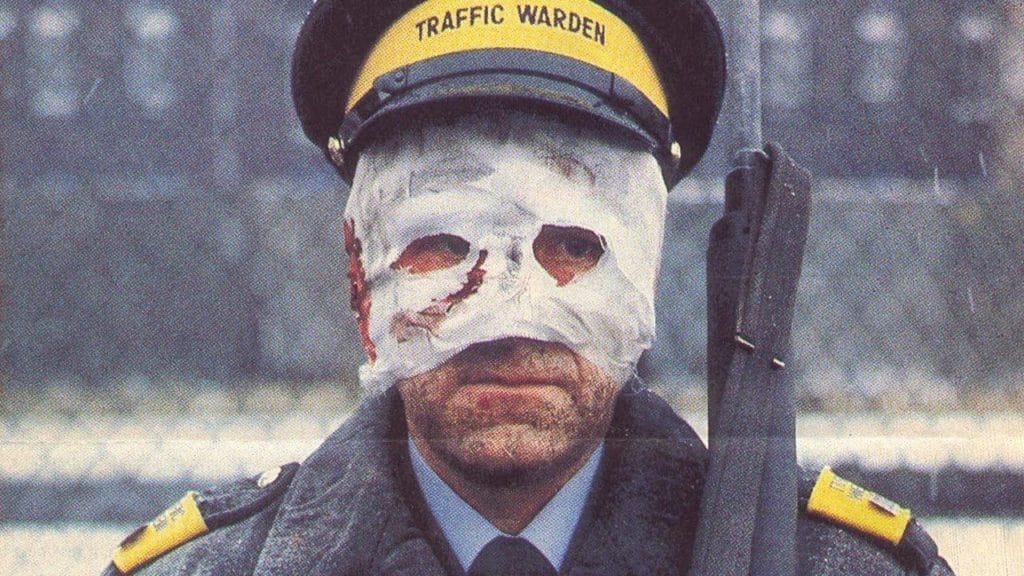

It’s not the shots of nuclear mushroom clouds that frighten me in Threads, though. It’s the inability of anyone to actually do anything to help. When the nuclear blast hits, the team appointed to help are trapped in their own offices. And, above them, it’s pandemonium. People screaming in the streets, trying to get to makeshift shelters. But there is no point. The survivors, trapped and terrified, quickly begin to realise that there is no point in living. And it is the eerie scenes after the attack that terrify the most – a woman cradling a scorched baby; an elderly man playing with tin soldiers. No water. No food. Nuclear winter. A man leaving the house after he realises his wife is dead, only to die himself in the streets.

Then there is the prospect of ten years after the attack. Children with stunted language development and growth. People working in the fields. And a teenager giving birth to something that horrifies her, and the audience – except the camera cuts away. It’s that last image that plays in your mind.

A film with a limited budget, then, but one which had an incredible impact – perhaps more of an impact than many audiences realise. President Reagan apparently requested a private viewing upon hearing about Threads. And remarkably, after that, relations between East and West seemed to improve, policy towards nuclear war changed. Threads exposed the ugly reality of the destruction of our world. Maybe it was best for everyone it did.