By Keri O’Shea

For many horror fans who first came into contact with Edgar Allan Poe via an illustrated volume, it’s likely that, in their minds, Poe’s fiction is forever associated with one artist in particular. Other artists before and after the illustrator in question have turned their hand to Poe, not least the great Decadent artist Aubrey Beardsley, but the 1919 illustrated edition, masterminded by an unassuming Irishman called Harry Clarke, seems to have become irrevocably intertwined with Poe’s tales.

Clarke, a Dubliner, grew up immersed in the emergent, very modern schools of art which continued to blossom during and after the deliciously-vibrant fin de siècle years. At this time, an upsurge in experimental art, music and literature rang out the Victorian era in an effusion of lurid colour, moral questions and questionable morals. Aesthetic representation at this time in some senses seemed torn between old and new, the heady and the sparse; the crowded symmetry of the Arts and Crafts movement (think William Morris) segued into increasingly stylised human forms, meticulous detail becoming itself unrealistic.

Clarke worked tirelessly during his lengthy career within illustration and stained glass (which has to be seen to be believed – go to Dublin to do so) and during this time, he dealt with a wide range of subjects, but – like many artists who fell under the Decadent influence in their formative years – he was drawn towards literary works which focused on ‘the perverse and sinister’. To return to Beardsley, an artist who undoubtedly had an effect on the young Clarke, he is well-known for his illustrations of Oscar Wilde’s works as well as of Poe, Wilde himself being drawn to Decadent themes such as the ‘femme fatale’ and deviant psychology. When it comes to Poe, he is therefore in many ways an obvious choice for illustration, for anyone interested in such themes.

Clarke’s illustrations for Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination are relentless, recognisable and still remarkable. This is not a verdict which has developed over time, either; they were instantly popular, and although their style was innovative, people took to them happily and quickly. Even in 1919, the edition was selling for a staggering 5 guineas (easily several hundred pounds in today’s money). Although the illustrations themselves do owe a debt to Beardsley’s own, utilising a similar level of fine detail and stylised nature, for example, Clarke’s own work adds more fluidity, more natural lines. Significantly, he doesn’t shy away from depicting the key moments of horror, either. In terms of unflinching focus, Clarke’s work seems to tip the hat to the sensationalist popular literature of the ‘penny dreadfuls’ of previous years in places; he isn’t afraid of peopling his pages with the more-dead-than-alive Madeleine Usher, or those in the throes of torture, or those committing murder.

There are twenty-nine illustrated tales in all, and illustrations for each. Rather than discuss them all here, I have picked three which I particularly like or find particularly significant – though, if you haven’t yet seen the full array of these brilliant pieces of artwork, I recommend you to find the rest.

The Premature Burial

The fear of being buried alive still exists, even in the modern and medicalised world – and it’s become a mainstay of modern horror on its own terms. The opening scenes of Broken (2006) depict an agonising struggle to escape a premature burial; go back beyond that, and with typical overkill, Fulci shows us that the only thing worse than waking up in a coffin is the method of rescue. Still, it isn’t a going concern for us – at least in the West – in the way that it was in Poe’s day. When Poe was writing, and for decades beyond that, people actively feared being buried before death. Primitive health care, frequent epidemics, a tendency for people to die at home and an inability to store corpses hygienically there or anywhere meant that the time between death/’death’ and burial could be very short indeed. Tales abounded of people sitting bolt upright at their own funerals; grave-robbers disclosed that on occasion, their prizes would be unearthed with their knees forced up, as if trying to kick away the coffin lid, or the coffins would bear scratch marks on the inside; you could even purchase a ‘safety coffin’, designed to allow you to alert others should you succumb to live burial. Perhaps Poe’s protagonist in ‘The Premature Burial’ isn’t so insane after all, given all of this, but yet his level of obsession with the risk that his catalepsy would mean he’d share this fate is so extreme that he cannot live his life ordinarily.

Clarke captures that moment of utter terror and panic which Poe’s character fears so much. Clarke’s is an ambiguous figure, however; the tree’s roots have passed the coffin’s lid, insinuating a length of time has passed, but the buried man (looking directly at the viewer) still appears alive; his hands look skeletal on first glance, but not on another. Clarke has effectively communicated the terror and the torpor of the character; the great space between coffin and surface emphasises the hopelessness of his fate.

The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar

Hypnosis to us is usually the stuff of light entertainment, but when the practice of ‘magnetism’ was first pioneered by Franz Anton Mesmer in the late Eighteenth Century, it was viewed as revolutionary, a sort of mysterious half-way house between science and magic when any understanding of the workings of the mind was notional at best. Its recognised potential to fix the unfixable – health ailments, mental disorders – allowed it to cement itself into fringe health care where to an extent, it remains. Edgar Allan Poe, being Edgar Allan Poe, hyper-extends the possibilities of hypnosis to pose a devious question, a morbid ‘what if?’

Here, a man is mesmerised by his friend when on the point of dying from tubercolosis; seven months are allowed to go by with him in this condition, neither alive nor dead, with Ernest Valdemar held in a horrendous limbo. He has all the appearance of death, yet his consciousness exists – somewhere, and can be questioned, although his answers are unenlightening. He is, he communicates, both ‘alive’ and ‘dead’. Eventually, they decide to release him from this condition. Clarke has chosen the story’s gruesome conclusion for this piece of art, where Valdemar is at last released from his hypnotised trance, and suddenly dissolves, into seven months’ worth of “detestable putrescence”. His decayed form, stark against the white bedlinen, oozes and leaks as he finally sinks into death-proper. To all intents and purposes, he looks like a forerunner of our own dead-alive, zombies.

The Tell-Tale Heart

Aberrant mental states were Poe’s bread and butter and this tale – the first Poe tale I ever read – is in many ways one of his absolute cruelest. The protagonist (antagonist?) of The Tell-Tale Heart murders a defenceless, elderly neighbour on nothing more than a whim; he admits as much, conceding that the old man had never done him any harm, but he carefully plans his murder regardless. It’s a Poe story, like The Black Cat, which I find uncomfortable reading even today. And yet, in reading about his meticulous planning and cover-up (a clear influence on Poe reader and scholar Fyodor Dostoevsky in Crime and Punishment), I can still feel some grain of pity for this troubled criminal. The more he protests his sanity, the more it’s clear he’s insane.

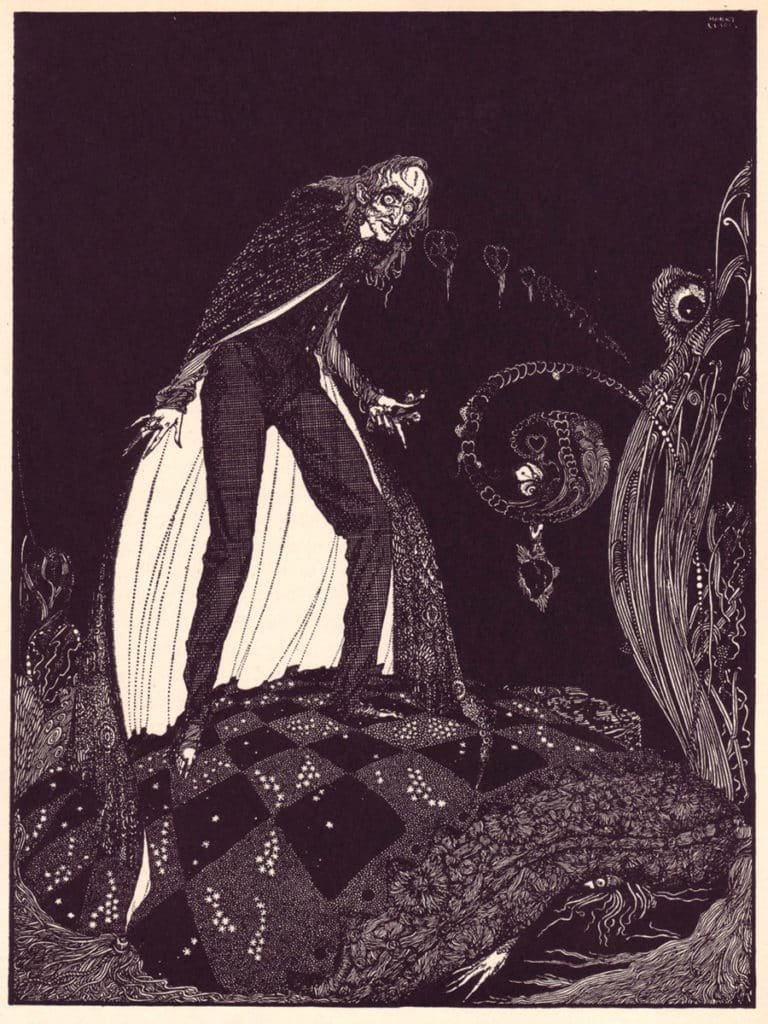

Clarke illustrated two stages of the story, but I have chosen this one – which is after the crime itself – because I think it’s incredibly interesting, not to mention ahead of its time. Here, the certainty and focus of the young man shown as he commits the murder is gone, and Clarke shows some evidence of the fracturing of his state of mind. He stands, haunted by his perception of the old man’s beating heart from beneath the floorboards where he’s concealed. He’s half-terrified, half-transfixed.

Clarke has shown the man’s awareness of the beating of the ‘hideous heart’ in a way which foreshadows comic book art of generations to follow: a pattern of numerous human hearts is shown gracefully emanating from the floor, their tendrils reaching out to the protagonist, inescapable. It’s a novel technique and a skilled balance of the beautiful and grotesque. The whole room is distorted and unreal, with a bizarrely-curving floor and a nightmarish eye adding to the effect of persecution and paranoia.

Then, of course, there’s the figure of the dead man itself; our criminal is lost to us, looking elsewhere as he is haunted by his deeds – but the old man peeps out at us, looking straight at us, wild and reproachful. The result is a disturbing one. Just as Poe forces us to confront the murder, so does Clarke’s illustration – by giving us an idea of how this culpability feels to Poe’s character. Like all of Clarke’s work on Poe, it’s both unflinching and insightful.