You have to hand it to Keanu Reeves. He may have been a huge star ever since breaking through as one half of the affable, dim-witted metalhead duo in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure a full three decades ago, yet for the longest time he was widely deemed impossible to take seriously as a dramatic actor thanks to notoriously wooden, awkward turns in the likes of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and The Devil’s Advocate. Yet against all odds, the man whose most iconic utterance is “woah” was able to carve a niche for himself as an action hero via Point Break, Speed and most notably The Matrix; and even more unexpectedly, he was able to return to that territory in recent years with the John Wick movies, having not only proven himself as a physical action performer, but also having genuinely gained some gravitas as a serious leading man. It obviously doesn’t hurt that he looks nothing like his 54 years, still boasting as lithe a physique and as lustrous a head of hair as he did in the 1990s. (The bastard.)

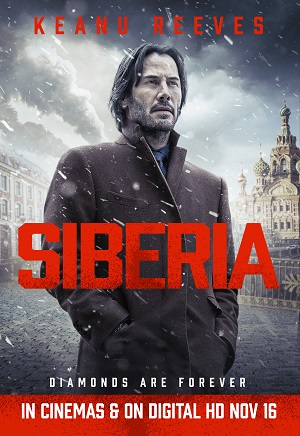

On paper, the John Wick persona doesn’t seem too difficult to shift over to other material. Just put Keanu in a sharp suit, with tidy mid-length hair and a closely trimmed beard, keep his dialogue minimal and to the point, and don’t ask him to emote too much, whilst hinting at a hotbed of repressed anxiety bubbling just below the surface. Lucas Hill, the lead protagonist in Siberia, fits this bill pretty well, so it’s not too big a surprise that the film’s PR material goes to some length to promote a link between the properties, suggesting that director Matthew Ross’s film is a suitable stop-gap for any Reeves fans impatient for John Wick 3. However, if you go in to Siberia expecting two hours of adrenaline-charged, guns-blazing, all-kicking all-punching entertainment, you’re liable to be disappointed. Indeed, there’s a strong likelihood you’ll be underwhelmed either way, as this is a slow, quiet, ponderous affair which may aspire to an old school crime thriller ambience, but winds up a little too understated to make much of an impression.

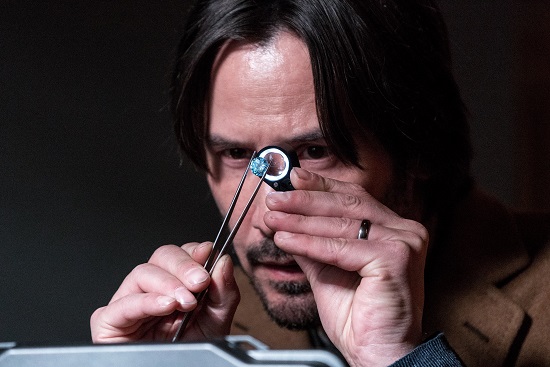

Lucas Hill (Reeves) is an American businessman of dubious legality. He’s in St. Petersburg to sell some ultra-rare, ultra-valuable blue diamonds to Russian mobsters, headed up by the somewhat intense Boris Volkov (Pasha D Lynchnikoff). However, what should be a relatively simple transaction proves more complex than anticipated when Hill’s contact for the diamonds isn’t where he was expected to be, forcing Hill to trek out of the big city and into a remote Siberian province where he’s told his contact is hiding out. In the bitter cold with nothing to do but wait and drink vodka, Hill finds himself drawn to local bar owner Katya (Ana Ularu), and – against the older man’s better judgement, as back home in the States he has a wife (an almost blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo from Molly Ringwald) – the two embark on what promises to be a brief affair. However, as further complications impede the diamond deal, the growing bond between Hill and Katya only adds to the steadily mounting problems, threatening to put them both in grave danger.

Lucas Hill (Reeves) is an American businessman of dubious legality. He’s in St. Petersburg to sell some ultra-rare, ultra-valuable blue diamonds to Russian mobsters, headed up by the somewhat intense Boris Volkov (Pasha D Lynchnikoff). However, what should be a relatively simple transaction proves more complex than anticipated when Hill’s contact for the diamonds isn’t where he was expected to be, forcing Hill to trek out of the big city and into a remote Siberian province where he’s told his contact is hiding out. In the bitter cold with nothing to do but wait and drink vodka, Hill finds himself drawn to local bar owner Katya (Ana Ularu), and – against the older man’s better judgement, as back home in the States he has a wife (an almost blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo from Molly Ringwald) – the two embark on what promises to be a brief affair. However, as further complications impede the diamond deal, the growing bond between Hill and Katya only adds to the steadily mounting problems, threatening to put them both in grave danger.

Written by Scott B Smith (novelist and screenwriter behind A Simple Plan and The Ruins), Siberia seems intent on harking back to the tone and aesthetic of the late 60s/70s Hollywood thriller (think Point Blank or The Driver). There’s a sparse, vaguely abstract atmosphere, and as much interest in the state of mind of the protagonists as the intricacies of the criminal underworld they in which they live; a world, and a way of life, which the film indicates they have grown tired of, and are questioning their place in. Reeves exudes world-weariness throughout, presenting Hill as a man of clear intelligence and morality who nonetheless chooses to do what he knows to be wrong, not only in his line of work but also in his extra-marital relations. Sex is actually a much bigger part of the equation in Siberia than you might initially expect, with Reeves and Ularu having a number of fairly intense love scenes which, had they been shot and edited a little less tastefully, might have made it is easy to sell the film as an erotic thriller. Honestly, I wonder if it mightn’t have been a bad idea to push things further in that direction, for as it is there’s a somewhat detached, clinical feel to it all that rather leaves the viewer cold. Then again, given the setting of the title, perhaps that’s the idea.

The scenery is attractive (although curiously most of it was shot in Canada), Lynchnikoff makes for an agreeably excessive villain, and Reeves and Ularu are a handsome couple even if the chemistry between them is a little lacking. Alas, there’s really nothing here that hasn’t been done many times before and many times better, with a plot that veers between meandering and incomprehensible, and characters whose fate its hard to get particularly invested in. Again, much respect to Reeves for his recent career revival, which I certainly hope continues; but if it means more films like this, he might not want to hang up John Wick’s black suit too soon.

Siberia is available now in the UK on digital download and limited cinemas, from Signature Entertainment.

The festive season has always been a popular setting for horror movies. This may in part be a natural evolution of the old tradition for setting ghost stories on Christmas Eve, but I daresay it’s more of a Grinch-like reaction against the crassness, commercialism and artifice of the event in modern culture; how, as much as we might like to claim it’s all about togetherness and giving and bringing out the best in us all, for a great many of us everything that we do for the holiday is out of a sense of obligation, demanding we put on a brave face and attempt, often unsuccessfully, to bury old tensions for just the one day. The season’s ugly underbelly has been exposed in a great many festive shockers over the years, but where many of these – including but not limited to Black Christmas, Gremlins, and more recently

The festive season has always been a popular setting for horror movies. This may in part be a natural evolution of the old tradition for setting ghost stories on Christmas Eve, but I daresay it’s more of a Grinch-like reaction against the crassness, commercialism and artifice of the event in modern culture; how, as much as we might like to claim it’s all about togetherness and giving and bringing out the best in us all, for a great many of us everything that we do for the holiday is out of a sense of obligation, demanding we put on a brave face and attempt, often unsuccessfully, to bury old tensions for just the one day. The season’s ugly underbelly has been exposed in a great many festive shockers over the years, but where many of these – including but not limited to Black Christmas, Gremlins, and more recently

To address the most obvious key strength right away, The Secret of Marrowbone does boast an impressive young ensemble. The horror audience is, of course, most likely to be familiar with Charlie Heaton from his role on Stranger Things, Mia Goth from Nymphomaniac Vol 2, and Anna Taylor-Joy – playing a local girl who becomes a close friend of the Marrowbones – from The Witch and Split. However, the real focal point is George MacKay, with whom I’d been totally unfamiliar beforehand. While I’m not certain this is necessarily a star-making turn, the actor does a good job with what he’s given, which is ostensibly a fairly meaty role: a young man forced into patriarchal responsibilities before his time, torn between duty to his siblings and the desire to live a life of his own, specifically with Taylor-Joy’s love interest. Naturally, as things progress, it veers off into darker territory for all concerned, though it’s worth stressing that this is by no means a wall-to-wall chiller; for the most part it’s a largely grounded, character-based period drama, with only occasional allusions to a supernatural element which doesn’t really come to the forefront until the final act.

To address the most obvious key strength right away, The Secret of Marrowbone does boast an impressive young ensemble. The horror audience is, of course, most likely to be familiar with Charlie Heaton from his role on Stranger Things, Mia Goth from Nymphomaniac Vol 2, and Anna Taylor-Joy – playing a local girl who becomes a close friend of the Marrowbones – from The Witch and Split. However, the real focal point is George MacKay, with whom I’d been totally unfamiliar beforehand. While I’m not certain this is necessarily a star-making turn, the actor does a good job with what he’s given, which is ostensibly a fairly meaty role: a young man forced into patriarchal responsibilities before his time, torn between duty to his siblings and the desire to live a life of his own, specifically with Taylor-Joy’s love interest. Naturally, as things progress, it veers off into darker territory for all concerned, though it’s worth stressing that this is by no means a wall-to-wall chiller; for the most part it’s a largely grounded, character-based period drama, with only occasional allusions to a supernatural element which doesn’t really come to the forefront until the final act. Whilst for many of us post-apocalyptic narratives may be synonymous with zombies and/or marauding biker gangs in extravagant costumes, pare it back and they typically come down to the same key idea: being the last person alive in a world that is no more. From Robert Neville of Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, to Max Rockatansky in George Miller’s Mad Max series, any self-respecting post-apocalyptic story tends to come down to one person, or a small group of people, doing what they can to stay alive, all on their own. Then, when invariably it comes to light that they are not in fact the last living soul on Earth, the question soon arises as to whether they might have been better off if they had been; Hell is other people, after all. So it is in I Think We’re Alone Now, director Reed Morano’s understated drama about solitude, survival and the difficulty of human relationships. Bronx Warriors this ain’t.

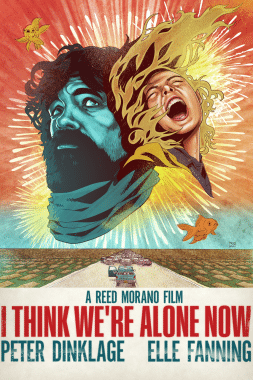

Whilst for many of us post-apocalyptic narratives may be synonymous with zombies and/or marauding biker gangs in extravagant costumes, pare it back and they typically come down to the same key idea: being the last person alive in a world that is no more. From Robert Neville of Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, to Max Rockatansky in George Miller’s Mad Max series, any self-respecting post-apocalyptic story tends to come down to one person, or a small group of people, doing what they can to stay alive, all on their own. Then, when invariably it comes to light that they are not in fact the last living soul on Earth, the question soon arises as to whether they might have been better off if they had been; Hell is other people, after all. So it is in I Think We’re Alone Now, director Reed Morano’s understated drama about solitude, survival and the difficulty of human relationships. Bronx Warriors this ain’t. Given that he’s arguably the best-loved actor in arguably the best-loved TV show of recent years, the presence of Peter Dinklage in the lead is clearly the main selling point of I Think We’re Alone Now. It’s an interesting choice for the actor, as Del is a total 180 degree turn from Tyrion Lannister. Where the Game of Thrones character enjoys the company of others almost as much as he enjoys the sound of his own voice, Del is a total introvert who doesn’t make a sound if he can help it, and clearly struggles when forced to interact with another human being. It only makes things harder that Elle Fanning’s Grace is such a polar opposite to him; far younger, considerably more outgoing, rather less concerned with being neat, tidy, quiet and orderly. This essential set-up – an uptight, lonely individual forced to confront their feelings when a bold free spirit enters the life – is very familiar territory, and, via such indie dramas as Buffalo 66 and Garden State, it tends to walk hand-in-hand with the dreaded Manic Pixie Dreamgirl archetype, which Fanning’s Grace could clearly qualify as. This being the case, as there’s a clear age gap between the two leads, it would be very easy for things to get a tad bit creepy. Happily, for the most part this is avoided, with any sense of this being a lonely male wish fulfilment story being kept to a minimum; the temptation is there to attribute this to the fact that director and cinematographer Reed Morano is female (probably best known for her work on another noted TV series, The Handmaid’s Tale), although we can’t fail to note that the screenwriter Mike Makowsky is not.

Given that he’s arguably the best-loved actor in arguably the best-loved TV show of recent years, the presence of Peter Dinklage in the lead is clearly the main selling point of I Think We’re Alone Now. It’s an interesting choice for the actor, as Del is a total 180 degree turn from Tyrion Lannister. Where the Game of Thrones character enjoys the company of others almost as much as he enjoys the sound of his own voice, Del is a total introvert who doesn’t make a sound if he can help it, and clearly struggles when forced to interact with another human being. It only makes things harder that Elle Fanning’s Grace is such a polar opposite to him; far younger, considerably more outgoing, rather less concerned with being neat, tidy, quiet and orderly. This essential set-up – an uptight, lonely individual forced to confront their feelings when a bold free spirit enters the life – is very familiar territory, and, via such indie dramas as Buffalo 66 and Garden State, it tends to walk hand-in-hand with the dreaded Manic Pixie Dreamgirl archetype, which Fanning’s Grace could clearly qualify as. This being the case, as there’s a clear age gap between the two leads, it would be very easy for things to get a tad bit creepy. Happily, for the most part this is avoided, with any sense of this being a lonely male wish fulfilment story being kept to a minimum; the temptation is there to attribute this to the fact that director and cinematographer Reed Morano is female (probably best known for her work on another noted TV series, The Handmaid’s Tale), although we can’t fail to note that the screenwriter Mike Makowsky is not. Here at Warped Perspective, and in our previous incarnation Brutal As Hell, we’ve long been massive enthusiasts for the weird and wonderful indie horror films of Japan. Be it the bizarre and challenging visions of director Sion Sono, the eye-popping practical FX work of Yoshihiro Nishimura, or the fearless performances of Asami, we’re used to getting excited at soon as we get word of a new such film making its way back west. However, we’re somewhat less accustomed to a new Japanese horror comedy arriving in a whirl of hype and praise from the international festival circuit which stretches beyond the specialist genre events, with the (for want of a better word) straight audiences greeting it as warmly as the horror aficionados.

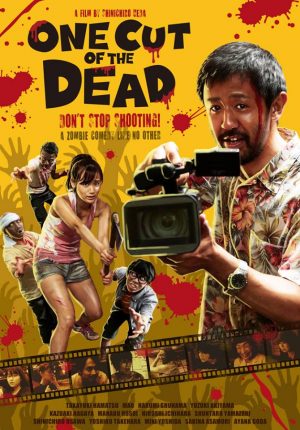

Here at Warped Perspective, and in our previous incarnation Brutal As Hell, we’ve long been massive enthusiasts for the weird and wonderful indie horror films of Japan. Be it the bizarre and challenging visions of director Sion Sono, the eye-popping practical FX work of Yoshihiro Nishimura, or the fearless performances of Asami, we’re used to getting excited at soon as we get word of a new such film making its way back west. However, we’re somewhat less accustomed to a new Japanese horror comedy arriving in a whirl of hype and praise from the international festival circuit which stretches beyond the specialist genre events, with the (for want of a better word) straight audiences greeting it as warmly as the horror aficionados. As the film begins, we get the impression that we’re joining a cheesy low-budget horror movie somewhere in the middle, as a blood-spattered, scantily clad young woman (Yuzuki Akiyama) faces off against a slowly-oncoming young male zombie (Kazuaki Nagaya), who it seems was until recently her boyfriend. She screams, she cries, she meets her fate… and then someone calls ‘cut,’ as it turns out we’re seeing a scene being shot for a movie. We also learn very quickly that the film’s director (Takayuki Hamatsu) is, well, just a little bit uptight and perhaps a little too serious about the filmmaking process, as his aggressive, ultra-demanding approach is clearly inflicting major psychological damage on his cast and crew, and pushing them way behind schedule. Whilst the team take a break, partially at the insistence of the somewhat matriarchal make-up artist (Harumi Shuhama), it becomes apparent that the director’s dedication to capturing real horror and real emotion knows no bounds, as the remote set suddenly finds itself under attack by the actual living dead, and – rather than make a dash for safety – the director is determined to get it all on camera.

As the film begins, we get the impression that we’re joining a cheesy low-budget horror movie somewhere in the middle, as a blood-spattered, scantily clad young woman (Yuzuki Akiyama) faces off against a slowly-oncoming young male zombie (Kazuaki Nagaya), who it seems was until recently her boyfriend. She screams, she cries, she meets her fate… and then someone calls ‘cut,’ as it turns out we’re seeing a scene being shot for a movie. We also learn very quickly that the film’s director (Takayuki Hamatsu) is, well, just a little bit uptight and perhaps a little too serious about the filmmaking process, as his aggressive, ultra-demanding approach is clearly inflicting major psychological damage on his cast and crew, and pushing them way behind schedule. Whilst the team take a break, partially at the insistence of the somewhat matriarchal make-up artist (Harumi Shuhama), it becomes apparent that the director’s dedication to capturing real horror and real emotion knows no bounds, as the remote set suddenly finds itself under attack by the actual living dead, and – rather than make a dash for safety – the director is determined to get it all on camera. Recent months have been a busy time for Jackie Chan fans, or at least it feels that way around these parts, as we’ve had a slew of the Hong Kong action superstar’s hits released to Blu-ray in the UK (

Recent months have been a busy time for Jackie Chan fans, or at least it feels that way around these parts, as we’ve had a slew of the Hong Kong action superstar’s hits released to Blu-ray in the UK (

Horror fans, at their best, are a very open-minded but also fiercely loyal bunch. Make one great movie and we’ll make damn sure to see your next; make a bunch of them and we’ll show up every time. Even more so, put together a cast with a string of genre favourites to their name, and watch the gorehounds turn out in their droves. And no two ways about it, Death House boasts one of the most impressive ensembles of seasoned horror icons that you’re ever likely to see. A quick scan of the cast list should be enough to make any true blue horror fan’s eyes pop out of their skulls: Barbara Crampton, Kane Hodder, Dee Wallace, Adrienne Barbeau, Bill Moseley, Tony Todd, Sid Haig, Michael Berryman, Vernon Wells, Debbie Rochon, Tiffany Shepis, Felissa Rose, Lloyd Kaufman, Camille Keaton, Brinke Stevens, Danny Trejo (for some reason uncredited) – and, perhaps the greatest jewel in an already glittering crown, the late, great Gunnar Hansen, who also wrote the story that was the basis for the screenplay.

Horror fans, at their best, are a very open-minded but also fiercely loyal bunch. Make one great movie and we’ll make damn sure to see your next; make a bunch of them and we’ll show up every time. Even more so, put together a cast with a string of genre favourites to their name, and watch the gorehounds turn out in their droves. And no two ways about it, Death House boasts one of the most impressive ensembles of seasoned horror icons that you’re ever likely to see. A quick scan of the cast list should be enough to make any true blue horror fan’s eyes pop out of their skulls: Barbara Crampton, Kane Hodder, Dee Wallace, Adrienne Barbeau, Bill Moseley, Tony Todd, Sid Haig, Michael Berryman, Vernon Wells, Debbie Rochon, Tiffany Shepis, Felissa Rose, Lloyd Kaufman, Camille Keaton, Brinke Stevens, Danny Trejo (for some reason uncredited) – and, perhaps the greatest jewel in an already glittering crown, the late, great Gunnar Hansen, who also wrote the story that was the basis for the screenplay. Or could it simply be that filmmakers like Death House’s director and screenwriter B Harrison Smith just aren’t up to the task? The only other film I’ve seen from Smith thus far, his 2014 debut

Or could it simply be that filmmakers like Death House’s director and screenwriter B Harrison Smith just aren’t up to the task? The only other film I’ve seen from Smith thus far, his 2014 debut  The last few years have been a curious time for mainstream horror. For one, pretty much every time a major new genre entry arrives, people seem to go out of their way to insist that it is not, in fact, a horror movie, primarily because the film in question is intelligent, nuanced and character-based, and handles genre tropes in an unexpected way. There’s a lot to be said for this approach, and it’s certainly given us a lot of great cinema (much of which, it should be stressed, dates back a great deal earlier than 2015). However, there’s also a great deal to be said for the more ostensibly straightforward, less high-reaching/inward-gazing mode of horror, in which the filmmakers are not quite so concerned with producing unorthodox, challenging fare than they are with just giving us a good old-fashioned roller coaster ride that gets the blood pumping. Happily, despite the rising tide of understated intellectual horror, Hollywood hasn’t forgotten how to make simpler, crowd-pleasing, shits and giggles horror, as Overlord most agreeably demonstrates.

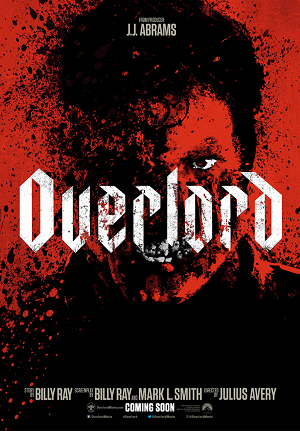

The last few years have been a curious time for mainstream horror. For one, pretty much every time a major new genre entry arrives, people seem to go out of their way to insist that it is not, in fact, a horror movie, primarily because the film in question is intelligent, nuanced and character-based, and handles genre tropes in an unexpected way. There’s a lot to be said for this approach, and it’s certainly given us a lot of great cinema (much of which, it should be stressed, dates back a great deal earlier than 2015). However, there’s also a great deal to be said for the more ostensibly straightforward, less high-reaching/inward-gazing mode of horror, in which the filmmakers are not quite so concerned with producing unorthodox, challenging fare than they are with just giving us a good old-fashioned roller coaster ride that gets the blood pumping. Happily, despite the rising tide of understated intellectual horror, Hollywood hasn’t forgotten how to make simpler, crowd-pleasing, shits and giggles horror, as Overlord most agreeably demonstrates. So we see, from its premise alone, Overlord is pretty far removed from the predominant high profile/high brow horror movies of recent years. After all, nothing screams ‘low brow’ with quite such relish and exuberance as a Nazi zombie movie. While this subgenre dates back decades (to the likes of Shock Waves and Oasis of the Zombies), it’s been particularly popular in the 21st century, entries ranging from the sublime (the Dead Snow movies), to the ridiculous (also the Dead Snow movies), to the somewhat less memorable (the Outpost movies, plus a slew of microbudget, supermarket bottom shelf DVD titles). However, correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t recall any big budget Hollywood Nazi zombie movies until now. Kind of surprised it’s taken this long, really; and while JJ Abrams isn’t exactly the first name you’d associate with Hollywood horror, his track record as a producer, most notably the Cloverfield series (which, it seems, this film was initially intended to be part of, until The Cloverfield Paradox appeared to kill off the loose franchise earlier this year), it’s not surprising he’d recognise the mainstream potential of the concept. Abrams also has a knack for recognising relatively untested directorial talent (i.e. Matt Reeves and Dan Trachtenberg on the two good Cloverfields), and brings another good ‘un to the forefront on Overlord in director Julius Avery, who proves himself more than a dab hand at high octane action and shock horror.

So we see, from its premise alone, Overlord is pretty far removed from the predominant high profile/high brow horror movies of recent years. After all, nothing screams ‘low brow’ with quite such relish and exuberance as a Nazi zombie movie. While this subgenre dates back decades (to the likes of Shock Waves and Oasis of the Zombies), it’s been particularly popular in the 21st century, entries ranging from the sublime (the Dead Snow movies), to the ridiculous (also the Dead Snow movies), to the somewhat less memorable (the Outpost movies, plus a slew of microbudget, supermarket bottom shelf DVD titles). However, correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t recall any big budget Hollywood Nazi zombie movies until now. Kind of surprised it’s taken this long, really; and while JJ Abrams isn’t exactly the first name you’d associate with Hollywood horror, his track record as a producer, most notably the Cloverfield series (which, it seems, this film was initially intended to be part of, until The Cloverfield Paradox appeared to kill off the loose franchise earlier this year), it’s not surprising he’d recognise the mainstream potential of the concept. Abrams also has a knack for recognising relatively untested directorial talent (i.e. Matt Reeves and Dan Trachtenberg on the two good Cloverfields), and brings another good ‘un to the forefront on Overlord in director Julius Avery, who proves himself more than a dab hand at high octane action and shock horror.  When we think of horror films which trap our protagonists in the wilderness far from civilisation, these tend to be backwoods shockers in the Texas Chain Saw/Hills Have Eyes mould, pitting the softer city folk against brutal, frequently inbred country bumpkins. Alternatively, such a setting might see its human cast at the mercy of some sort of unusually large and aggressive animal. When you boil it right down, though, such narratives are invariably about humankind versus the elements, how flesh and bone invariably stands no chance against the timeless, ageless, unstoppable ravages of nature. 1978 Australian horror movie Long Weekend explores this idea in a hugely compelling and inventive manner, centring on a struggling married couple played by John Hargreaves and Briony Behets who, at the husband’s behest, venture out to a remote, secluded beach for a getaway, in the hopes of saving their relationship. However, it quickly becomes evident that not only their relationship is beyond saving, but that they themselves have little hope of getting out of there alive, as nature itself seems set on destroying them.

When we think of horror films which trap our protagonists in the wilderness far from civilisation, these tend to be backwoods shockers in the Texas Chain Saw/Hills Have Eyes mould, pitting the softer city folk against brutal, frequently inbred country bumpkins. Alternatively, such a setting might see its human cast at the mercy of some sort of unusually large and aggressive animal. When you boil it right down, though, such narratives are invariably about humankind versus the elements, how flesh and bone invariably stands no chance against the timeless, ageless, unstoppable ravages of nature. 1978 Australian horror movie Long Weekend explores this idea in a hugely compelling and inventive manner, centring on a struggling married couple played by John Hargreaves and Briony Behets who, at the husband’s behest, venture out to a remote, secluded beach for a getaway, in the hopes of saving their relationship. However, it quickly becomes evident that not only their relationship is beyond saving, but that they themselves have little hope of getting out of there alive, as nature itself seems set on destroying them. The 1970s saw the rise of James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis and the beginnings of Green politics and environmental awareness, and these certainly seem to make their presence felt in Long Weekend. While ostensibly the main focus is on the couple’s relationship rapidly falling apart before our eyes, the film also makes a repeated point of emphasising their total disregard for their surroundings: without a moment’s thought the pair toss their garbage, spray bugs, kill wildlife, and generally smash up the wilderness to better suit themselves. Hargreaves’ Peter in particular, while fancying himself the outdoors type, wreaks the most havoc, chopping down a tree with an axe and shooting at birds willy-nilly for no better reason than to amuse himself. There’s little debate on his contemptuousness, then, nor does Behets’ Marcia do much to redeem herself; indeed, there’s no avoiding that from early on both parties are presented as thoroughly unsympathetic, leaving us rooting for nature to take its revenge from early on. (That having been said, some viewers are likely to take exception to the reported event which is implied to have been Marcia’s greatest ‘crime against nature.’)

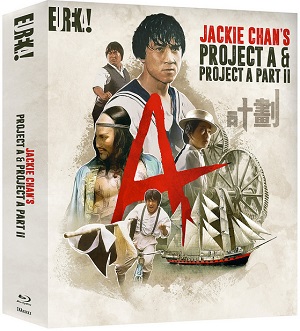

The 1970s saw the rise of James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis and the beginnings of Green politics and environmental awareness, and these certainly seem to make their presence felt in Long Weekend. While ostensibly the main focus is on the couple’s relationship rapidly falling apart before our eyes, the film also makes a repeated point of emphasising their total disregard for their surroundings: without a moment’s thought the pair toss their garbage, spray bugs, kill wildlife, and generally smash up the wilderness to better suit themselves. Hargreaves’ Peter in particular, while fancying himself the outdoors type, wreaks the most havoc, chopping down a tree with an axe and shooting at birds willy-nilly for no better reason than to amuse himself. There’s little debate on his contemptuousness, then, nor does Behets’ Marcia do much to redeem herself; indeed, there’s no avoiding that from early on both parties are presented as thoroughly unsympathetic, leaving us rooting for nature to take its revenge from early on. (That having been said, some viewers are likely to take exception to the reported event which is implied to have been Marcia’s greatest ‘crime against nature.’) It’s been quite a year for British fans of Jackie Chan, thanks to the fine folks at Eureka Home Entertainment. Not content with reissuing the screen legend’s breakthrough film Drunken Master on Blu-ray

It’s been quite a year for British fans of Jackie Chan, thanks to the fine folks at Eureka Home Entertainment. Not content with reissuing the screen legend’s breakthrough film Drunken Master on Blu-ray

Yes, I realise I’m a little late to the party with this one given that at the time of writing David Gordon Green’s Halloween has been in cinemas just over a week, and to the tune of the highest box office takings in franchise history no less. But if we’re speaking in terms of who’s showing up a little late, there are plenty who’d say the Halloween series is well overdue a return to screens. With Rob Zombie’s reboot and its sequel now the best part of a decade behind us, and almost unanimously dismissed by critics and fans as a mistake, the 40th anniversary of John Carpenter’s groundbreaking slasher presented an irresistible opportunity to set Michael Myers back on his reign of terror. While the choice of Green as director may have raised some eyebrows given his inexperience with horror (aside from his having long been attached to the Suspiria remake before vacating the director’s chair for

Yes, I realise I’m a little late to the party with this one given that at the time of writing David Gordon Green’s Halloween has been in cinemas just over a week, and to the tune of the highest box office takings in franchise history no less. But if we’re speaking in terms of who’s showing up a little late, there are plenty who’d say the Halloween series is well overdue a return to screens. With Rob Zombie’s reboot and its sequel now the best part of a decade behind us, and almost unanimously dismissed by critics and fans as a mistake, the 40th anniversary of John Carpenter’s groundbreaking slasher presented an irresistible opportunity to set Michael Myers back on his reign of terror. While the choice of Green as director may have raised some eyebrows given his inexperience with horror (aside from his having long been attached to the Suspiria remake before vacating the director’s chair for  Of course, given that, for better or worse, we’ve already had 10 Halloween movies, and Carpenter’s film has inspired literally countless imitators, you might be forgiven for going into Halloween 2018 wondering whether it’s all been done already. I’m not sure whether that’s the case or not, but of this much I’m sure: if there’s still some life left in Halloween, this film doesn’t find it. Not at all. As much as I recall H20, Resurrection and the Rob Zombie entries leaving me infuriated, at least I came out of those films feeling something. This time around, I’m stunned by the total lack of feeling. As much as it might aim to be reverential of the original, and balance this out with some grounded family-based drama, it all adds up to a whole lot of nothing.

Of course, given that, for better or worse, we’ve already had 10 Halloween movies, and Carpenter’s film has inspired literally countless imitators, you might be forgiven for going into Halloween 2018 wondering whether it’s all been done already. I’m not sure whether that’s the case or not, but of this much I’m sure: if there’s still some life left in Halloween, this film doesn’t find it. Not at all. As much as I recall H20, Resurrection and the Rob Zombie entries leaving me infuriated, at least I came out of those films feeling something. This time around, I’m stunned by the total lack of feeling. As much as it might aim to be reverential of the original, and balance this out with some grounded family-based drama, it all adds up to a whole lot of nothing. This, really, is the crux of the problem: with the exception of Matichak, and Jibrail Nantambu as an unbelievably cute and funny little kid being babysat for, none of the new characters are remotely interesting. The whole thread that gets things in motion, British podcasters trying to score interviews with both Michael and Laurie, is tedious as all hell. Michael’s new doctor, and his role in proceedings, is boring and obvious. There are a slew of would-be comedic asides – cops on stakeout comparing lunches, a boy on a hunt complaining about missing dance class, pretty much all the high school sequences – that totally miss the mark, and leave you wondering how the hell they made the final cut; particularly when so many of the more significant scenes between Curtis and Judy Greer are so badly edited, clearly trimmed down for fear of challenging the audience’s attention span. Greer herself, though a good actress, seems really out of sorts for the most part, and we really never get a strong mother-daughter vibe (even considering their estrangement) between her and Curtis.

This, really, is the crux of the problem: with the exception of Matichak, and Jibrail Nantambu as an unbelievably cute and funny little kid being babysat for, none of the new characters are remotely interesting. The whole thread that gets things in motion, British podcasters trying to score interviews with both Michael and Laurie, is tedious as all hell. Michael’s new doctor, and his role in proceedings, is boring and obvious. There are a slew of would-be comedic asides – cops on stakeout comparing lunches, a boy on a hunt complaining about missing dance class, pretty much all the high school sequences – that totally miss the mark, and leave you wondering how the hell they made the final cut; particularly when so many of the more significant scenes between Curtis and Judy Greer are so badly edited, clearly trimmed down for fear of challenging the audience’s attention span. Greer herself, though a good actress, seems really out of sorts for the most part, and we really never get a strong mother-daughter vibe (even considering their estrangement) between her and Curtis.