David Lynch’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel ‘Dune’ emerged in 1984 to a double whammy of both box office failure and a vicious critical drubbing. Not that these are in themselves perfect indications of a film’s inherent lack of value or cultural longevity; 1982’s Blade Runner was also a critical and box office flop, albeit one that attracted almost total critical rehabilitation and mainstream popularity with the release of a director’s cut in 1991. Despite Dune’s failure, and its lack of critical rehabilitation, in part due to its director’s absolute refusal to complete a director’s cut, 1984’s Dune still holds a special place in the landscape of cinematic science fiction, attracting adoration and derision in equal measure, with fan cuts appearing online in the absence of an official directorial one. Lynch himself refers to Dune with regret and in terms that suggest its making nearly broke him. This year heralds the release of a long-awaited Dune adaptation by critical darling Denis Villeneuve, so what better time to take a look at its big screen predecessor?

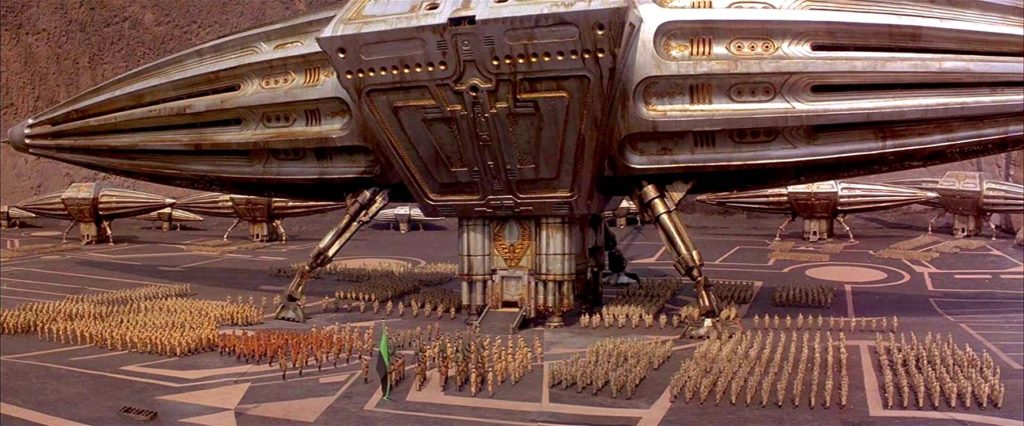

Lynch’s Dune was made with the expectation that it would be the next Star Wars – a hugely profitable, and eventually multi-part space mythos upon which a thousand even more profitable merchandising deals could be launched. George Lucas’s 1977 blockbuster had saved cinema from a near-fatal financial decline in the 70s and Lucas’s Industrial Light and Magic team had developed special effects in a very short period to the point that things once thought impossible to portray believably onscreen now seemed very possible indeed. If Dune were to be made successfully, now seemed the time to do it, with the appropriate technical advances and audiences seemingly hungry for epic space adventures.

It was not to be though, for what in hindsight are fairly obvious reasons.

Although Herbert’s Dune is acknowledged to be a primary influence on the early Lucas saga, Dune is a vastly more complicated and difficult property. While on one level it seems that if a mass general audience can understand an evil vast space empire overseen by a scheming Emperor (Palpatine), a noble set of rebels (the rebel alliance), a mysterious, robed, religious order of monk-like figures with mystical mind tricks, fighting skills and odd weapons (the Jedi) and a young male hero with a destiny (Luke Skywalker), it could just as easily accept an exploitative space empire overseen by a scheming Emperor (Shaddam IV), a fierce set of desert warriors rebelling against them (the Fremen), a young male hero with a destiny (Paul Atreides), and a mysterious, robed, religious order of nun-like figures with mystical voice and fighting powers (the Bene Gesserit Sisterhood), it was not to be. Star Wars keeps things very simple and relatable in terms of story and character, presenting black hats vs white hats; a limited cast of simple heroes and villains with a final redemption arc. Star Wars is a family-friendly, simple and enjoyable space western that doesn’t ask you to think much. Dune’s source material is quite the opposite – adult-oriented, with an extended cast of characters, and dealing with more complex intrigues and grey morality.

Frank Herbert’s Dune

Herbert’s original novel might be best described in layman’s terms as a galactic Game of Thrones meets Lawrence of Arabia. Dune is set in a feudal far-future where royal houses plot and war against each other for control of the imperial throne and the precious commodity on which all interplanetary trade and thus power depends – the mysterious spice ‘Melange’.

Melange is mined on the harsh desert planet Arrakis, nicknamed ‘Dune’, which is occupied by the cruel aristocratic House Harkonnen to mine the spice, and populated by a secretive desert people known as ‘Fremen’. Giant, ferocious sandworms prove the main danger in the bleak desert environment. Consumption of melange allows the development of a kind of clairvoyance, or prescience; the ability to pick up flashes of the future. It is this spice-fuelled prescience that allow the Spacing Guild’s strange, mutated navigators to plot the safest course between planets. The spice is also of great importance to the inscrutable female Bene Gesserit religious order who scheme, plot, and navigate smoothly among the Imperial court and the royal houses in pursuit of power, via their telepathic abilities and the results of their own thousand-year breeding program, with the ultimate long-term goal of producing a genetic superhuman – the Kwisatz Haderach – a solitary male with perfect prescience, and fully developed Bene Gesserit abilities who will advance their political cause rather than his own.

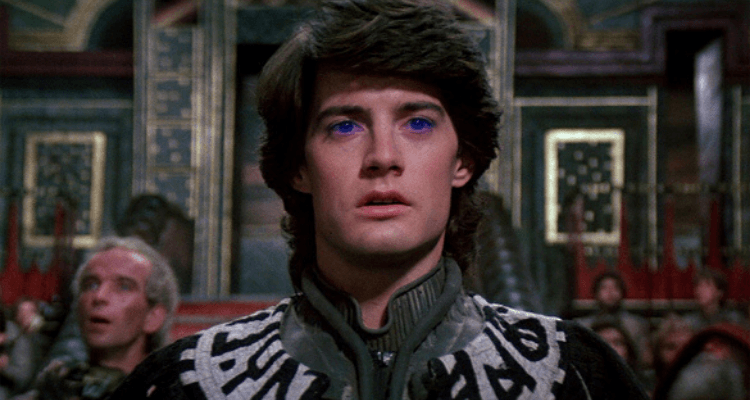

Caught up in the above machinations is one Paul Atreides, sole heir of House Atreides by his Bene Gesserit mother, the Royal Lady Jessica, who was part of the Kwisatz Haderach breeding program but broke ranks to produce a male heir – Paul – for the Duke Atreides. House Atreides is the victim of plotting by the Imperial House; the Harkonnens and the Spacing Guild and Paul and Jessica are dispossessed and forced to flee into the desert of Arrakis, where they join the Fremen. After a series of trials, Paul becomes leader of a local Fremen rebellion against the cruel occupying House Harkonnen and ultimately plots to unseat the Emperor of the Known Universe himself, taking his place. Jessica is aware of the mythology seeded among the tribal peoples on the planet by the Bene Gesserit order, and to ensure their survival among the tribe, exploits it to portray Paul as a long-prophesized Fremen messiah figure. Paul’s becomes an unwilling god-figure, as his spice-fuelled prescience allows him increasing glimpses of the genocidal horrors that his own jihad will unleash across the universe, long after he is dead.

Dune lacks funny aliens, endearing robots, or indeed much obvious humour or heart-warming detail at all. It deals with age-old power struggles and grand human intrigue rather than extra-terrestrials, with guerrilla warfare and ‘desert power’ replacing lasers and epic space battles. It warns of the dangers of following charismatic leaders and how even with the purest of intentions, power inevitably corrupts, with even well-meaning leaders overwhelmed by the apparatus of the cult they build around themselves. It’s a novel where people speak obliquely to each other at best, and are constantly second-guessing each other’s loyalties and intent. The large cast of characters engage in endless internal monologuing, and the hero’s vaunted destiny is actually a rather troubling galactic genocide, albeit one he is desperately trying to avert. The language is often difficult, too, with names and concepts drawn from everything from Scandinavian languages to Arabic to 11th century Talmudic scholars. It’s a novel that even at first glance is highly problematic in terms of turning it into a compact, workable screenplay that remains loyal to the original text.

Development Hell

Lynch’s Dune was the conclusion of a nearly decade and a half of development hell. David Lean was first mooted to direct in the early seventies after Planet of the Apes producer Arthur P. Jacobs acquired the rights. When Jacobs died in 1974, the rights were sold to a French production company with notorious Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky set to direct. It’s hard to imagine more disparate visionaries – the British director of sweeping epics Lawrence of Arabia, Bridge on the River Kwai and Doctor Zhivago, and the self-styled ‘psychomage’ and director of lurid, surrealistic, small budget madness destined for an anti-establishment cult audience receptive to extreme depictions of sexual violence, gore and drug use. Given Lean’s credentials and handling of Lawrence of Arabia, a story that itself is one of the great influences on Herbert’s Dune, a David Lean Dune adaptation remains a tantalizing thought.

It is Jodorowsky’s Dune that to this day seems to hold a strange and enduring fascination for many, including some fans of the book who seem to believe – oddly in my view – that he would have conjured up a superior or perhaps definitive adaptation of Herbert’s epic masterwork. Perhaps this is due to his bringing onboard extraordinary visual talents such as legendary French comic artist Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, science fiction special effects supremo Dan O’Bannon, Swiss artist H.R. Giger, and science fiction illustrator Chris Foss, with a soundtrack by fresh-off-the-dark-side-of-the-moon Pink Floyd, rather than any commitment to respecting the integrity of Herbert’s novel, given Jodorowsky’s stated intention to produce a Dune that ‘raped’ Frank Herbert’s book. In the 2013 documentary ‘Jodorowsky’s Dune’ he states that his vision would have paid little attention to the facts of the plot, and would be akin to, in his own words, ‘a twelve-hour LSD trip’. I’m not sure in what world a twelve-hour LSD trip with little attention paid to Herbert’s story would have proved in the least bit marketable or reaped the box office and critical success that Lynch’s could not. Nor would it, by all reports, have pleased fans of Herbert’s novel by almost completely discarding its narrative and themes for a Carlos Castaneda-esque, acid-drenched film of a length usually reserved for documentaries about the Holocaust and featuring stunt casting such as Salvador Dali as the Emperor of the Known Universe, ruling from atop a fancy golden toilet, and mind-bogglingly, Stones’ frontman Mick Jagger as Feyd Rautha Harkonnen. Then again, Lynch did eventually lumber us with the similarly ludicrously-cast (and clad) Sting in the same role. Jodorowsky’s Dune may have been great in its own way, a good-looking piece of psychedelia, or a horribly dated and self-indulgent mess that would have attracted a very small cult audience, but perhaps ultimately would be no more and perhaps less remembered and loved/hated than Lynch’s Dune.

Of course, we’ll never know, having only the admittedly splendid Dune concept art produced by H.R. Giger, Giraud and Foss, and Jodorowsky’s proclamations of his own genius to go on. Jodorowsky’s French funding predictably fell through due to his intractability on matters of creative control and his refusal to consider making a film with a remotely marketable length. By 1976 the rights had been sold on again, this time to Dino De Laurentis, the prolific Italian producer of spaghetti westerns, big screen, big budget Hollywood flops such as 1976’s King Kong, and iconic films such as the controversial Death Wish (1974), Barbarella (1968), gritty Pacino-led police drama Serpico (1973), Conan the Barbarian (1983), the Stephen King adaptation The Dead Zone (1982) and 1980’s camp classic Flash Gordon. Never one to shy away from a challenge, and with a seeming ability to throw cinematic mud at a wall and come up trumps as often as not, De Laurentis set about hiring Frank Herbert to produce a screenplay, and Ridley Scott, a former BBC set designer and commercial advertising director fresh off his second feature film – 1979’s hugely successful Alien – to direct. Alien had benefited hugely from previous Dune cast-offs, O’Bannon (this time on script duties) and Giger’s now iconic creature designs. In fact, Jodorowsky’s commissioned artwork for Dune would seemingly influence production design on mainstream films for decades to come.

Initially, Scott was enthusiastic about the project, but dropped out of the production after the tragic death of his brother and the realisation that making Dune would take up several years of his life. At least, that’s the explanation Scott gives. It has been mooted by multiple sources that a major bone of contention between De Laurentis and Scott was the script which put the hero Paul Atreides and his mother Jessica in an incestuous sexual relationship, not only a completely disrespectful and distasteful deviation from the original text, but certainly a bridge too far by some miles in terms of making a marketable high budget film, and the disagreement on the matter allegedly ended with Scott being fired. Scott was hired to work on another major science fiction film – Blade Runner – and the rest is cinema history. De Laurentis was forced to cast about for another visionary capable of bringing the epic to fruition.

Which brings us to David Lynch.

David Lynch and Dune

“I started selling out on Dune. Looking back, it’s no one’s fault but my own. I probably shouldn’t have done that picture, but I saw tons and tons of possibilities for things I loved, and this was the structure to do them in. There was so much room to create a world.” (David Lynch)

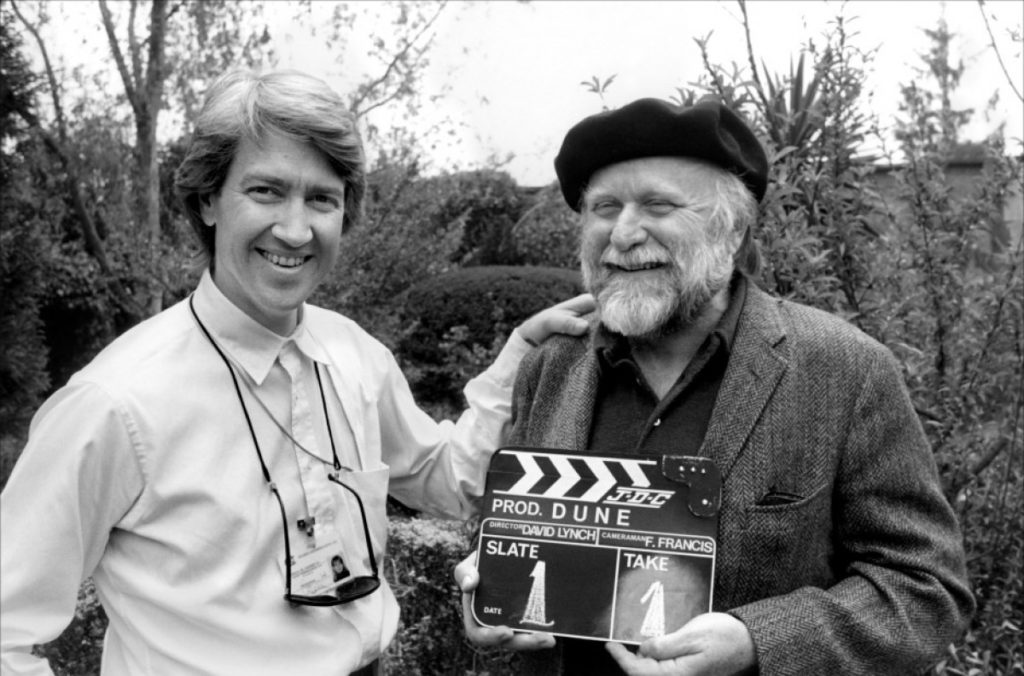

Offers to direct big-budget studio pictures poured in for David Lynch after his second film, 1980’s Academy and BAFTA-nominated The Elephant Man. Raffaella De Laurentis offered Lynch Dune on the strength of this film, which combined Lynch’s strange surrealistic visual touches with a traditionally straightforward historical narrative which connected strongly with audiences and critics. It was perhaps a combination of visual flair, emotional connection and narrative strength De Laurentis hoped Lynch could bring to the futuristic and often bleak, high-handed and alienating world of Dune. Dune was to be Lynch’s big break into big budget, big studio, mainstream filmmaking, having turned down George Lucas’s offer to direct Return of the Jedi. It was a break he was to regret, eventually sending him hurtling back to smaller scale, independent productions. Just as with Jodorowsky and his backers a decade earlier, the major conflict was not over his interpretation of the novel or his visual excesses. De Laurentis gave Lynch his head in every creative aspect apart from the final cut of Dune, which needed, according to the studio, to be of a marketable length, both as not to repel audiences with an overlong picture, but to allow cinemas as many showings as possible during a normal working day in order to recoup its exorbitant costs quickly. It’s a lesson studios had learned the hard way in the 1960s with the notorious, studio-destroying Elizabeth Taylor-led epic Cleopatra: an insanely costly film with a just as insanely long running time simply won’t allow enough showings to recoup its costs even when sold out for months ahead, even when that film takes more money overall than any other that year. Dune was about to become a very costly movie indeed, and despite taking more money than any David Lynch film to date, was fated to be financially scuppered by its initial costs.

Dune was filmed principally on location in Mexico City, for financial reasons (the peso had helpfully just collapsed against the dollar) and for the access to the all-important desert. All sound stages were occupied at Churubusco Studios, and money poured into ornate costuming and sets. No expense was spared. Lynch had sets built with luxury woods and imported marble. He had teams of seamstresses sewing ornate silk dresses and hand-embroidering cloaks that would barely be seen on camera or if filmed, often end up on the cutting room floor. Soldiers from the Mexican army were hired in their thousands as extras to play the Fremen in desert scenes. The shoot was beset with mishaps and traumas; Jurgen Prochnow (Duke Leto), after narrowly escaping a serious injury from an exploding overhead lighting rig, was scarred by a special effect placed on his face. Francesca Annis (Lady Jessica) was badly burned by an exploding gas stove in her accommodation. The veteran actor Aldo Ray, originally cast as Baron Harkonnen, showed up in such a state of alcoholic dissolution and ill-health that he couldn’t work and had to be recast at short notice. The power kept going out. Phone lines were scarce to the point of non-existence. Lack of environmental regulation allowed the burning of tyres to create suitably thick smoke for one battle scene – toxic smoke that choked the cast into uselessness. Extras clad in the extraordinary-looking sculpted latex stillsuit costumes fainted in the brutal desert heat. Both cast and crew were beset with constant food poisoning to the point Virginia Madsen (Princess Irulan) had to be propped up with a barstool under her crinolines during filming one scene, after a bout of persistent vomiting left her too ill to even stand unaided. Lynch and Rafaella De Laurentis slowly but surely fell out, the producer trying to chivvy things along on budget, the director wanting to improvise new scenes and approaches and realise his vision.

Costs naturally spiralled. In the end, Dune ended up costing a then unheard of $42 million to make; by comparison, 1983’s ILM effects-drenched blockbuster Return of the Jedi cost $32 million, and 1982’s seminal Blade Runner $28 million. The classic 1984 release The Terminator cost a pittance by comparison, coming in at under $7 million.

It’s easy to see where the money went. In the final analysis, the greatest strength of the film is in its visual worldbuilding. Sets and costume are richly detailed, and heavily reference Earth’s past in fashions and architecture, to eerie and mesmerizing effect. It’s a stylistic trick used to devastating effect in 1982’s Blade Runner, which used 40s-inspired fashions to signal the essential neo-noir quality of the story, with its hard-boiled detectives and poised femme fatales. Lynch’s Dune similarly portrays a far future visually rooted in Earth antiquity, where space guilds and religious orders wield extraordinary power. Baroque palaces and art deco spaceships sit alongside brutalist industrial landscapes; ritualistic knife duels exist in the same universe as strange sonic weaponry and the ability to fold space.

The opening scene, where a Third-Stage Guild Navigator, accompanied by an odd retinue in various and lesser stages of spice-evolution, rolls his giant, dripping spice-gas tank into the court of the Emperor of the Known Universe is a wonderful example of visual storytelling. While the scene works as a huge, stage-setting info-dump of what’s what and who’s who, the visual storytelling is what remains in the mind – the uneasy and distrustful relationship between three disparate power brokers. The Emperor and his court display all the old-world trappings of earthly wealth and power; golden furniture, jewels, ladies in waiting trailing corseted and crinoline-clad princesses, clusters of lapdogs led about by lackeys. By contrast, the repulsive, sneering navigators appear all function with little regard for human aesthetics, human comforts, or social niceties. Their bodies are unwholesomely medicalized, run through with tubes and oozing with odd liquids. Their costumes, bulky and unwieldy black carapaces, were made from old bodybags, rather fittingly for those engaged in leaving their humanity behind to pursue spice evolution. Gliding between them, distrusted by both, are the Bene Gesserit women, their curious flowing silk chador-like robes and shaven heads signalling a combination of strange monasticism and the soft manipulative power of the courtesan. It’s one of the most strangely compelling and atmospheric scenes in the film. It’s also one that doesn’t occur in the book and was entirely dreamed up by Lynch ; a confrontation between a horrific futuristic freak and a throwback to a 19th century European court, with their meeting complicated by an interfering religious order, it neatly that sets the stage for the power struggles to come.

Meanwhile, the aristocratic Atreides family’s muted earth-toned military uniforms, vast, enveloping fur collars and elegant, Belle Epoque silhouette dresses remind of nothing so much as the doomed Romanov family of Russia, remnants of a gilded age soon to disappear in the maelstrom of assassination, revolution and war. Their fabrics and surroundings are notably harmonious. Their ships reflect their concern with harmonious design inside and out. Their blood enemies the Harkonnens by contrast revel in industrial brutality. Their ships are lumpen, misshapen, threatening and ugly creations. They are clad in industrial webbing and sticky-looking synthetics, their colour palette of sickly institutional carbolic greens and blacks that of a hellish chemical plant, with the Baron at one-point luxuriating in a shower of black filth and oil raining down from an overhead vehicle. House Harkonnen is where Lynch pulls all the stops out to create visual signifiers of their obsession with humiliation and cruelty and their twisted, inhumane nature. The Harkonnens and their subordinates are gifted with shriekingly unnatural chemical-orange hair; random servants’ ears and eyes are sewn shut. A truly nasty Lynchian touch is the Harkonnen heartplug, a crude externalized medical device designed to enable a messy death via exsanguination (“Everyone gets one around here.”). The Baron himself, played with shouty, sweaty aplomb by Kenneth McMillan, is covered in gross, suppurating abscesses, which combined with his by-the-text predatory, sadistic homosexuality (portrayed by Lynch via a scene where he feverishly gropes an adolescent boy while removing his heart-plug, revelling in the blood splatter), some critics of the era viewed as a direct reference to the cancerous skin lesions suffered by end-stage AIDS patients in an era when the disease remained untreatable. Some critics felt this was unconscionable choice and somehow meant as a deliberate and direct insult to the gay community. It’s certainly a memorably and viscerally uncomfortable one that, long after the era of HIV as a death sentence ended, usefully externalizes the rot at the heart of the Harkonnen cause.

Other memorable visual touches include the bizarre resemblance of Freddie Jones’ ‘human computer’ mentat character Thufir Hawat to then recently deceased Soviet premier and late cold war icon Leonid Brezhnev. Brezhnev’s signature overgrown eyebrows also pop up on mentat Piter de Vries too, suggesting It’s some additional side-effect of their lip-staining thought-accelerant drug of choice. Actor Brad Dourif was given free rein to improvise a litany for the consumption of this ‘juice of Sapho’ which is so perfectly-pitched, so wonderful an addition to the lore of Dune, that is hard to believe didn’t come straight from the original novel:

“It is by will alone I set my mind in motion. It is by the juice of Sapho that thoughts acquire speed, the lips acquire stains, the stains become a warning. It is by will alone I set my mind in motion.”

It’s heart-breaking to wonder what other perfectly Dune moments like this were improvised or scripted then discarded, or filmed and thrown on the cutting room floor for matters of time. Indeed, the main flaws in Lynch’s vision lie almost entirely in the aforementioned issues with running time.

“I was making [Dune] for the producers not for myself. That’s why the right of final cut is crucial. One person has to be a filter for everything. I believe this is a lesson world; we’re supposed to learn stuff. But three and a half years to learn that lesson is too long.” (David Lynch)

Lynch’s preferred original cut was a full 3-hour edit, cut down from 4 hours of filmed material. He was then ordered to cut in down more, resulting in a 2 hour 17 minute theatrical cut. Voiceovers were imposed to try to bridge the narrative gaps left by endlessly cut scenes. In some places, this works rather well; the opening introductory monologue by Virginia Madsen’s Princess Irulan, whose aristocratic head materialises in and out of frame against a background of stars to inform us in cold and patrician tones of various facts regarding the upcoming story, has a singularly peculiar charm and in essence functions no differently from the celebrated opening text-crawl of a Star Wars movie. Anyone who read the book also recognises it as a nice nod to Irulan’s role as Paul Mu’ad Dib’s historian, whose commentaries provide context to various chapters of the novel.

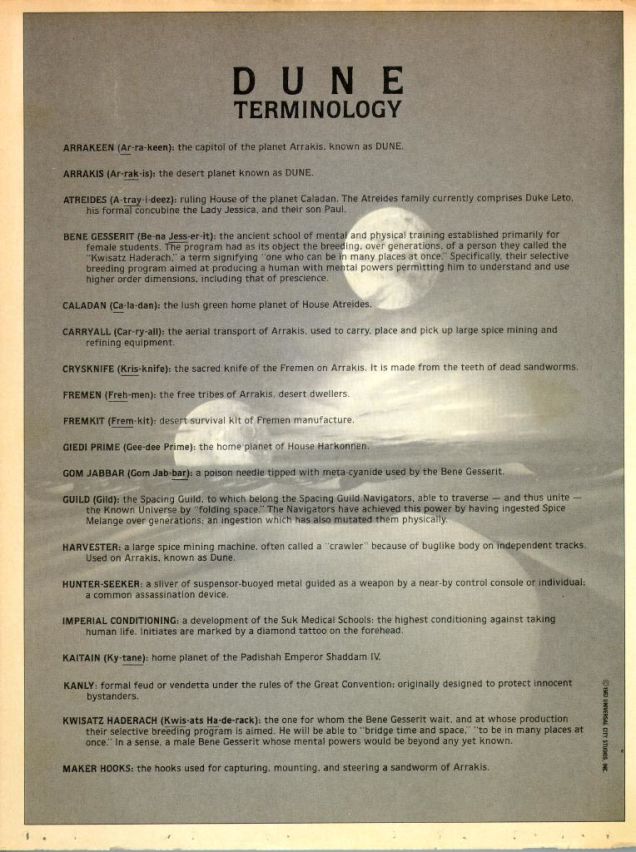

Despite Lynch going all out with the voiceovers and in-film explanations provided by Paul’s ‘filmbooks’, still the studio lacked confidence in the ability of audiences to comprehend what they were about to see, to the point of handing out glossaries of Dune terminology to cinemagoers in North America. How they expected audiences to consult this document in the darkness of the cinema is anyone’s guess. Perhaps it was meant to make sense of the film after the event, but what is for sure though is that it signalled a loss of faith in the film to speak for itself. Or perhaps they saw it as Star Wars, but with homework.

Whether the audience had done their homework or not though, the inserted voiceovers couldn’t fully compensate for the missing material. Huge chunks of character and plot-developing scenes disappear to the detriment of the film. Characters such as Duncan Idaho and Liet Kynes appear only to utter a couple of lines then die, their significance lost. The Fremen get little exploration of their customs and culture beyond their sudden allegiance to a boy they are convinced by events is their messiah. While the film takes time to work carefully and lovingly through scenes from the first part of the book; Paul’s testing with the gom jabbar by the Reverend Mother; his defeat of a Harkonnen hunter-seeker; Yueh’s betrayal and the escape into the desert, it starts to race over later events. Important developments were cut out for time – such as Paul’s first kill and the defeat of the Fremen challenger Jamis, which grants him entrance into the Fremen tribe. Jessica’s Bene Gesserit fighting skills i.e. ‘the weirding way’ are left unexplored apart from a woefully underplayed and unconvincing skirmish with Stilgar. Lynch’s active refusal to portray the weirding way as per the novel as a martial art that allows the practitioner lethal speed, strength and inhuman reflexes was probably rooted in contempt for the grindhouse cinema that martial arts movies, generally cheaply-made, badly-dubbed Hong Kong films, were confined to in that period. This fighting style wouldn’t be legitimized in western cinema until the advent of the Matrix films some decade and a half later. Lynch summarily dismissed the idea of the Bene Gesserit fighting art as ‘kung fu in the dunes’ and instead substituted his own obscure Atreides future technology – the ‘weirding modules’ – as the film’s signature weaponry, perhaps designed in the hope of becoming as iconic to his Dune as the lightsabre was to the successful Star Wars franchise. It’s actually an intriguing idea that adds another interesting layer of strangeness to the film – ancient battle cries transformed into lethal weaponry by science.

There is also distracting visual poetry – the repetitive, simple dreamscapes of Paul’s visions, the awesome roaring monstrousness of the sandworms created by Carlo Rambaldi, the birth sequence, the compelling sequence of travel via a mystical folding of space, all overlaid with an eerie Brian Eno synth and the wonderfully bombastic rock score of Toto. It’s all a universe away from the common expectations of science fiction at the time, which had long moved well away from Kubrick’s elegant and meditative 2001 and created expectations for more simplistic, action-packed, and fast-moving adventure. Certainly, nothing in the science fiction of the era prepared anyone for unsettling content such as a militant-looking and not awfully pleasant small child in Islamic-derived dress (Paul’s sister Alia) charged with assassinating an enemy, waving a large knife in ecstasy at the slaughter in the desert, and that was decades before the era of ISIS.

The final nail in the coffin for many is the matter of the ending, which manages to undermine the whole point of the novel – that Paul is a man playing god, not an actual god. One can twist the idea of Paul’s creating the miracle of rain on Arrakis, and killing the source of the spice stone dead, by implication throwing the universe into decay and darkness in one swift movement, as some kind of hamfisted reference to events much further down the path of Herbert’s Dune novels, which see the greening of Arrakis and the destruction of the order of the universe as part of a ‘golden path’; ultimately though, it reads as an infuriating, dumbed-down and plastered on ‘happy ending’ designed to neatly signal that our hero is awesome, and his journey is over; please go home. It’s not clear what Lynch really thought he was achieving here; the fact that he was actually working on the screenplay for Dune Messiah, the second novel in the Dune sequence, when Dune was released into cinemas suggests he was anticipating success and was far happier with the production, its outcome and the studio demands than he would later claim.

Ultimately, David Lynch’s Dune falls between two stools in failing to please either book purists or those looking for a coherent, unchallenging mainstream movie experience; it’s too off-book for the former, and both too earnestly on-book, and too viscerally weird and experimental in nature for the latter. Despite this, Lynch’s Dune still remains an enveloping, dreamlike, and sometimes nightmarish experience of a film quite unlike anything before or since. There’s a claustrophobic, smothering atmosphere created by the darkened interiors, mannered acting, urgent, whispered inner monologuing, and the weird, thrumming soundtrack. The occasional defects in FX are neither here nor there – there is some shoddy greenscreen and the odd off-putting dub, but it’s a unique and tantalising visual and mental ride for all that and unlike any other science fiction film yet made in its ambitious reach. Lynch’s interpretation of the Dune universe remains a compelling and unnerving, brain-churning fever dream of a film that fascinates and provokes strong reactions to this day. It’s one of those notorious failures that continues to compel curiosity well beyond some of the successes of its day. Perhaps it was all a just bit much for audiences in 1984, its tagline, ‘A world beyond your experience, beyond your imagination’ ironically and sadly apt.