In a stark opening scene, composed largely from a colour palette of black, white, and tiny amounts of red – a young woman awakens. She is in a mysterious room, has crippling injuries to her legs, and is clearly shocked and confused by her predicament. As soon as she wakes up, she’s addressed by a man: he gives his name, explains that she has been kidnapped, and she will remain in this room until such time as she “falls in love” with him. Before leaving her alone, he warns her not to try and escape – her legs are too damaged, the place they’re in is too isolated and she won’t get far.

In a stark opening scene, composed largely from a colour palette of black, white, and tiny amounts of red – a young woman awakens. She is in a mysterious room, has crippling injuries to her legs, and is clearly shocked and confused by her predicament. As soon as she wakes up, she’s addressed by a man: he gives his name, explains that she has been kidnapped, and she will remain in this room until such time as she “falls in love” with him. Before leaving her alone, he warns her not to try and escape – her legs are too damaged, the place they’re in is too isolated and she won’t get far.

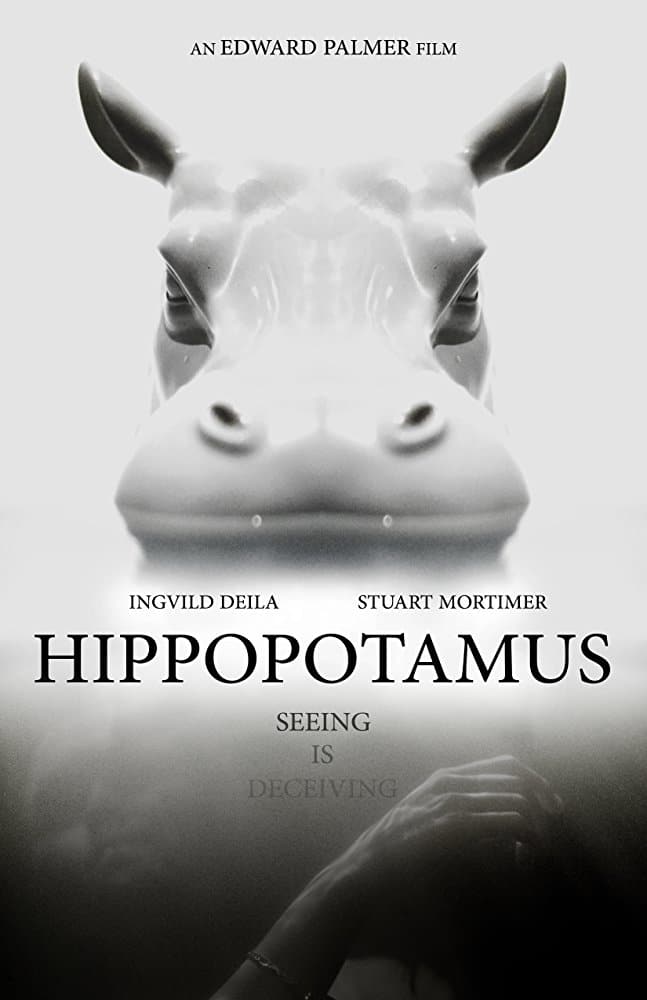

Now, an early proviso: the publicity for Hippopotamus (2017) – and also what I’ve just written above – sounds very much like an example of the maligned ‘torture porn’ genre, doesn’t it? The features are all there: the frightened woman, the confinement in a bleak, controlled environment, the apparently deliberately-inflicted injuries and the appearance of an apparently deranged captor who wants something extraordinary from these extraordinary circumstances. And I’ll be the first to admit that when I initially read the description for the film, I doubted very much whether there’d be anything here to engage me: I’ve seen a lot of films like these through the years. They tend to appeal to filmmakers on a budget, but less and less do they appeal to me. However, in how it all actually unfolds on screen, Hippopotamus is anything but a re-run of any of the most notorious ordeal horrors I could name. If anything, it’s an unusually low-key, compelling tale which runs in a quite different direction with the elements mentioned above.

The woman in captivity – Ruby – is told by her captor – Thomas – that she will be following a strict new schedule. She will be fed, she will be given medication, she will be slowly helped to heal, and her sleep will be controlled. It’s soon clear that Ruby has no idea who she is: she keeps looking with wonder at a bracelet engraved with her name, and when she gets to look at some of her possessions, kept in a nearby handbag, she’s confused by them, too. As she begins to feel more well, she begins to ask questions of Thomas, though he is not exactly forthcoming (captors in cinema rarely seem particularly garrulous). He does assure her, though, that he hasn’t kidnapped with any sexual intentions; Ruby can barely believe this, asking several times if she has been assaulted. She doesn’t endure any further cruelty, though, which begins to encourage her to dig deeper; she becomes increasingly confident with this man, and he begins to warm to her.

The woman in captivity – Ruby – is told by her captor – Thomas – that she will be following a strict new schedule. She will be fed, she will be given medication, she will be slowly helped to heal, and her sleep will be controlled. It’s soon clear that Ruby has no idea who she is: she keeps looking with wonder at a bracelet engraved with her name, and when she gets to look at some of her possessions, kept in a nearby handbag, she’s confused by them, too. As she begins to feel more well, she begins to ask questions of Thomas, though he is not exactly forthcoming (captors in cinema rarely seem particularly garrulous). He does assure her, though, that he hasn’t kidnapped with any sexual intentions; Ruby can barely believe this, asking several times if she has been assaulted. She doesn’t endure any further cruelty, though, which begins to encourage her to dig deeper; she becomes increasingly confident with this man, and he begins to warm to her.

One of the film’s key strengths, though, is that nothing simply unfolds in an anticipated way in Hippopotamus. Firstly, the film’s timeframe is disorientating. Conversations repeat verbatim, or very nearly; seconds drag, or they fly by. The camera pans sideways through the same room, showing what could be minutes, hours or days. This sets up the viewer to feel as confused as Ruby does, unsure of who to trust or what to believe. One thing which is certain, however, is that despite the likely expectations, this is a largely bloodless, gore-free film. The lion’s share of its impact comes from its examination of relationships under extreme duress – and there are some bizarre and original revelations along the way.

Perhaps even more so, Hippopotamus is a story about memory – and how deeply vulnerable we are when this part of ourselves is missing. How can you judge what someone is saying to you, if you have no idea of who you even are, where you have been, where you are? The slow reveals and developments which add to the characterisation here – brilliantly handled by actors Ingvild Deila and Tom Lincoln – held my attention really well. It can be no easy thing for two people in one confined set to keep the audience rapt, though of course credit must also go to writer and director Edward A. Palmer, in his first feature-length film, for keeping the script and the edits on the money. See, I’ll admit that I found some of the plot developments a little strange, or strained maybe, but because of how successfully the film overall engenders this sense of disorientation, you just have to accept what you see. Nothing seems certain here – the audience can judge nothing with complete certainty. Similarly, perhaps a few moments more of explication at the end of the film would have given me something more concrete to come away with, but overall I think that Hippopotamus goes out the way it comes in – full of surprises and perplexity. We’re kept on the same level as Ruby throughout; there’s no omniscient perspective for us. Who’s fooling who here – and are we being fooled?

I would say that if you are expecting a conventional horror yarn here with the prerequisite victimhood/torment/grisly content, then Hippopotamus isn’t for you; this is instead a highly unusual exploration of theme and trope, at times tranquil and at times tense, but always a deeply uneasy watch. A day on from my viewing, I’m still mulling it over; in a world of so many tried-and-tested film projects, I’d say this is high praise indeed.

Hippopotamus (2017) will be screening on 19th April 2018 as part of the East End Film Festival in London. For further information, including ticketing, please click here.