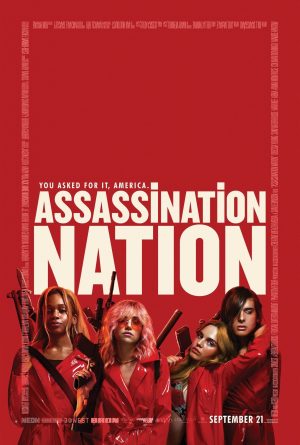

As someone who writes about films, it’s always a telling moment when you find yourself approaching a particular review with trepidation. Given that, at the time of writing, pretty much an entire week has passed since I saw Assassination Nation at Celluloid Screams 2018, there’s no denying that this is one such film I feel a little anxious about tackling. Much of the audience at the Saturday night screening in Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema appeared to react very enthusiastically indeed to writer-director Sam Levinson’s film, and I gather it’s been inspiring similar responses in its many festival screenings since premiering at Sundance. It’s a film which goes out of its way to do things by extremes, from its loud and brash colour schemes and soundtrack, to its hyper-kinetic camerawork and editing, and perhaps above all else its ultra-topical, ultra-timely commentary on the contemporary climate of sexual politics, social media, data hacking and the current wave of feminism. In tackling subject matter that is so close to the bone in 2018, Assassination Nation seems specifically designed to be scoured over academically, which can make it a bit harder to simply address its merits as a piece of filmmaking; and it plays a tricky balancing act between its ‘woke’ worldview and its aspirations toward vintage bad girl exploitation thrills, which I’m not sure it entirely succeeds in. This, however, is not to deny that Assassination Nation is a striking piece of work that merits a wide audience and widespread discussion.

As someone who writes about films, it’s always a telling moment when you find yourself approaching a particular review with trepidation. Given that, at the time of writing, pretty much an entire week has passed since I saw Assassination Nation at Celluloid Screams 2018, there’s no denying that this is one such film I feel a little anxious about tackling. Much of the audience at the Saturday night screening in Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema appeared to react very enthusiastically indeed to writer-director Sam Levinson’s film, and I gather it’s been inspiring similar responses in its many festival screenings since premiering at Sundance. It’s a film which goes out of its way to do things by extremes, from its loud and brash colour schemes and soundtrack, to its hyper-kinetic camerawork and editing, and perhaps above all else its ultra-topical, ultra-timely commentary on the contemporary climate of sexual politics, social media, data hacking and the current wave of feminism. In tackling subject matter that is so close to the bone in 2018, Assassination Nation seems specifically designed to be scoured over academically, which can make it a bit harder to simply address its merits as a piece of filmmaking; and it plays a tricky balancing act between its ‘woke’ worldview and its aspirations toward vintage bad girl exploitation thrills, which I’m not sure it entirely succeeds in. This, however, is not to deny that Assassination Nation is a striking piece of work that merits a wide audience and widespread discussion.

The action plays out in a small American town called Salem (too on the nose? We’re barely getting started). Our central protagonists are a quartet of popular, sex-positive high school girls, Lily (Odessa Young), Sarah (Suki Waterhouse), Em (Abra), and Bex (Hari Nef), and like a large percentage of their age group, their lives revolve around the friends, their phones, and near-constant partying. However, the party in Salem takes an unexpected turn when the personal data and internet history of various high profile local figures are released online by an anonymous hacker (by which we mean, you know, someone who’s hiding behind anonymity, not that they necessarily are… forget it). That which is revealed prompts outrage among the adults, ending careers and ruining lives overnight; whilst the reaction from local teens, our heroines included, is almost nothing but ‘LOLs.’ Yet it becomes apparent that the hack isn’t going to stop there, and soon enough literally everyone in Salem has their data leaked for all the world to see. The secrets that are now out in the open lead to hysteria and violence, a good portion of which winds up being directed towards the central quartet, as like any young people of note, they too have their share of skeletons in the closet. Yet as tempers flare ever more intensely, Salem’s townsfolk – the white males in particular – grow ever more anxious to find out who the hacker is, and bring them to justice. Of course, their particular definition of justice looks rather more like the wild west, and they’re just itching to get some lynching done – but our heroines are not about to be taken down that easily.

Full disclosure: I come to this film as a straight white cisgender male nearing the end of his thirties. This being the case, I’m acutely aware that I’m far from the primary intended audience of Assassination Nation, and by extension it’s certainly no accident or mere coincidence that I found much of it exhausting. In common with many of the most celebrated and/or reviled young rebel movies of the past two decades – Natural Born Killers, Fight Club, most recently Spring Breakers – Levinson’s film goes out of its way to overstimulate the audience with a constantly roving camera, a throbbing soundtrack, and machine-gun dialogue in an aggressively modern vernacular. The core quartet are clearly intended as inspirational figures for the young audience, women in particular. Certainly all of them have their flaws and make their share of mistakes which the film does not attempt to gloss over, but they own these, refusing to play the victim or accept the abuse that is hurled in their direction. They maintain this attitude from the Heathers/Mean Girls-esque beginnings, through to a more intense, emotional yet still grounded second act, all the way through into a frenzied, ultra-violent conclusion straight out of a Purge movie.

This progression from reasonably plausible small town drama into quasi-apocalyptic shoot-’em-up delirium seems key to the appeal of Assassination Nation; certainly it’s been deemed the main selling point, given that the film has been marketed almost entirely on images of the young leads in their eye-catching red raincoats holding guns. The thing is, while the film plays out in a ‘heightened’ fashion (pardon my use of that overused modern film criticism buzzword, typically utilised by poorly-read writers trying to deny genre), events still play out in a comparatively grounded and plausible fashion; or, at least, grounded and plausible by comparison with these stranger-than-fiction times America is currently living through. This being the case, when the final act centres on our oppressed and scapegoated young women fighting back by literally taking up arms, questions are invariably raised about whether Assassination Nation is truly advocating such a course of action; no small thing given what a sensitive subject gun control has also been in America in recent years. Even so, it’s not hard to pinpoint a shift in tone about two thirds in when the film makes clear it’s side-stepping into outright fantasia, with slasher/home invasion horror elements soon giving way to over-the-top action. And, of course, this is hardly the first film to balance a serious message of female empowerment with stylised theatrics and fantasy violence; take just about any women in prison or rape revenge movie from decades gone by.

It’s also curious to note that, while Assassination Nation presents itself as unabashed extreme cinema setting out to push as many buttons as possible – take its early ‘trigger warning’ montage, the focal point for the film’s first trailer – it actually rather feels like it’s holding back in some respects. Certainly guns, sexism, homophobia and fragile male egos are at the forefront, but racism doesn’t seem to come to the forefront despite the presence of a black lead in Abra’s Em. Transphobia is curiously diluted too, given that we also have a trans lead in Hari Nef’s Bex; who, while she absolutely faces hostility and bigotry, is still unanimously referred to throughout as a ‘she’ and by her chosen name, even by those baying for her blood. It is absolutely laudable that the film and its central characters do not treat Bex as anything but another girl (indeed, the fact that she’s trans isn’t even mentioned until some ways in), yet it seems a little self-defeating to imply that their belligerent, ignorant oppressors would still play nice about it even when they’re trying to kill her.

It’s also curious to note that, while Assassination Nation presents itself as unabashed extreme cinema setting out to push as many buttons as possible – take its early ‘trigger warning’ montage, the focal point for the film’s first trailer – it actually rather feels like it’s holding back in some respects. Certainly guns, sexism, homophobia and fragile male egos are at the forefront, but racism doesn’t seem to come to the forefront despite the presence of a black lead in Abra’s Em. Transphobia is curiously diluted too, given that we also have a trans lead in Hari Nef’s Bex; who, while she absolutely faces hostility and bigotry, is still unanimously referred to throughout as a ‘she’ and by her chosen name, even by those baying for her blood. It is absolutely laudable that the film and its central characters do not treat Bex as anything but another girl (indeed, the fact that she’s trans isn’t even mentioned until some ways in), yet it seems a little self-defeating to imply that their belligerent, ignorant oppressors would still play nice about it even when they’re trying to kill her.

All this having been said (and believe me, there’s plenty more that could be said about the film), there can be little question that Assassination Nation is a powerful and effective piece of work. After all, any film that leaves one with so much to say and say much to think about is always going to be noteworthy, for better or worse; and the fact that, even after a week of reflection and over 1200 words typed on the subject, I’m still not 100% sure how I feel about the film, only seems to confirm that Sam Levinson and company have succeeded in what they set out to do. It’s a movie that some are going to love and some are going to despise with an equal passion, but whichever side of the fence you fall on, it’s unlikely to leave your mind for some time thereafter. As such, it’s absolutely a film that I recommend everyone goes to see; your conclusions, as ever, will be your own.

Assassination Nation just screened at Sheffield’s Celluloid Screams; our thanks to all at the festival. It’s also set to screen at Abertoir Horror Festival in Aberystwyth, Wales, before getting a wide UK cinema release on 23rd November.

Tuesday, 13th November

Tuesday, 13th November Friday, 16th November

Friday, 16th November As has oft been noted, one of the great pleasures of attending film festivals, getting early looks at films which have yet to (or in some cases, never really do) reach a wide audience, is being caught by surprise by material of which you knew little or nothing beforehand. This is particularly the case when it’s a mystery movie, one of which Sheffield’s Celluloid Screams makes a point of including in its line-up every year. This year, around the stroke of twelve on the Saturday night, it was revealed that their 2018 mystery movie was You Might Be The Killer, a film of which I must confess to having been entirely ignorant beforehand. However, as soon as the poster art below was projected onto the Showroom Cinema screen, a slew of questions and preconceptions arose in my mind. So there’s Alyson Hannigan and Fran Kranz, both famous for their work with Joss Whedon; might this hint to the tone of what we’re about to see? There’s a vintage VHS vibe, so it seems fair to assume something a bit retro, yes? And it certainly seems a bit slasher-ish right away, which immediately makes Kranz’s presence in some ways a bit of a surprise; after all, he was in The Cabin In The Woods, specifically designed to be the last word on deconstructionist slasher/cabin horror, so where is there left to go from there?

As has oft been noted, one of the great pleasures of attending film festivals, getting early looks at films which have yet to (or in some cases, never really do) reach a wide audience, is being caught by surprise by material of which you knew little or nothing beforehand. This is particularly the case when it’s a mystery movie, one of which Sheffield’s Celluloid Screams makes a point of including in its line-up every year. This year, around the stroke of twelve on the Saturday night, it was revealed that their 2018 mystery movie was You Might Be The Killer, a film of which I must confess to having been entirely ignorant beforehand. However, as soon as the poster art below was projected onto the Showroom Cinema screen, a slew of questions and preconceptions arose in my mind. So there’s Alyson Hannigan and Fran Kranz, both famous for their work with Joss Whedon; might this hint to the tone of what we’re about to see? There’s a vintage VHS vibe, so it seems fair to assume something a bit retro, yes? And it certainly seems a bit slasher-ish right away, which immediately makes Kranz’s presence in some ways a bit of a surprise; after all, he was in The Cabin In The Woods, specifically designed to be the last word on deconstructionist slasher/cabin horror, so where is there left to go from there? When we met Sam (Kranz), he seems to be having a very bad night. He’s drenched in blood, gasping for breath, hiding in fear for his life, and in his hour of need he calls his best friend, comic book store owner and occult scholar Chuck (Hannigan, playing a role one can’t help but suspect was originally written for a man, not that the character’s gender has any bearing on proceedings). It transpires that Sam is out in a super-remote stretch of woodland where he’s setting up a summer camp on old family property, yet under circumstances he can’t quite recall off-hand, a masked madman armed with a huge, weird-looking machete showed up, and hacked up all the other camp counsellors. However, as Chuck talks Sam through it all, getting him to mentally retrace his steps and attempting to fill in the blank spots, the two friends reach what is for them a somewhat startling conclusion, although for the audience it’s not quite so hard to fathom given the film’s title: the man behind the mask is none other than Sam himself, under the influence of some sort of supernatural force beyond his comprehension.

When we met Sam (Kranz), he seems to be having a very bad night. He’s drenched in blood, gasping for breath, hiding in fear for his life, and in his hour of need he calls his best friend, comic book store owner and occult scholar Chuck (Hannigan, playing a role one can’t help but suspect was originally written for a man, not that the character’s gender has any bearing on proceedings). It transpires that Sam is out in a super-remote stretch of woodland where he’s setting up a summer camp on old family property, yet under circumstances he can’t quite recall off-hand, a masked madman armed with a huge, weird-looking machete showed up, and hacked up all the other camp counsellors. However, as Chuck talks Sam through it all, getting him to mentally retrace his steps and attempting to fill in the blank spots, the two friends reach what is for them a somewhat startling conclusion, although for the audience it’s not quite so hard to fathom given the film’s title: the man behind the mask is none other than Sam himself, under the influence of some sort of supernatural force beyond his comprehension. Nostalgia seems to be generational. Much as the 1980s saw an influx of renewed interest in the culture of the 1950s, and the 90s seemed to be all about attempting to relive the 60s, so too has our current decade seemed often overly fixated on looking back to the 80s. This trend that it has made its presence felt through vast swathes of contemporary media, most of it the handiwork of a new wave of thirtysomething creators presenting us with material that harkens back to their childhood years in that troubled, trashy, yet distinctive era.

Nostalgia seems to be generational. Much as the 1980s saw an influx of renewed interest in the culture of the 1950s, and the 90s seemed to be all about attempting to relive the 60s, so too has our current decade seemed often overly fixated on looking back to the 80s. This trend that it has made its presence felt through vast swathes of contemporary media, most of it the handiwork of a new wave of thirtysomething creators presenting us with material that harkens back to their childhood years in that troubled, trashy, yet distinctive era.

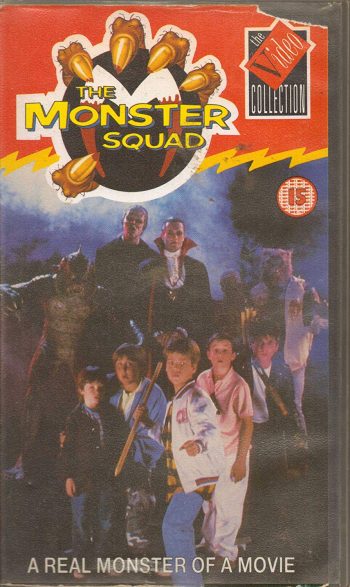

I’ll try to keep this as simple and concise as I can (not an easy task given my curse of verbal diarrhoea), for this is less an opinion piece than an outright demand: we, the British people – and yes, I do feel comfortable in presenting both myself and Warped Perspective co-editor Keri O’Shea as entirely representative of our nation (ahem) – demand our own physical media edition of The Monster Squad!

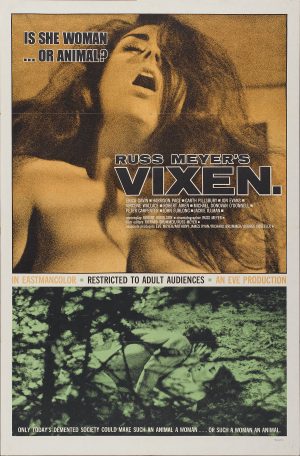

I’ll try to keep this as simple and concise as I can (not an easy task given my curse of verbal diarrhoea), for this is less an opinion piece than an outright demand: we, the British people – and yes, I do feel comfortable in presenting both myself and Warped Perspective co-editor Keri O’Shea as entirely representative of our nation (ahem) – demand our own physical media edition of The Monster Squad! Fifty years ago this week, the 16th feature film from American writer-director Russ Meyer – and the very first US production to be given the X-rating – had its premiere screening. Although, as with Meyer’s entire body of work, Vixen is now generally classed as a cult film, it was on release an unprecedented commercial success, a major career turning point for the exploitation filmmaker, and arguably as significant a film as any in setting the stage for the more permissive, confrontational and experimental American cinema of the decade that followed. Not a bad show for a director whose name will always first and foremost be synonymous with big tits.

Fifty years ago this week, the 16th feature film from American writer-director Russ Meyer – and the very first US production to be given the X-rating – had its premiere screening. Although, as with Meyer’s entire body of work, Vixen is now generally classed as a cult film, it was on release an unprecedented commercial success, a major career turning point for the exploitation filmmaker, and arguably as significant a film as any in setting the stage for the more permissive, confrontational and experimental American cinema of the decade that followed. Not a bad show for a director whose name will always first and foremost be synonymous with big tits. Spoilers ahead.

Spoilers ahead.

We can scarcely fail to mention that Niles’ near-conversion to communism comes in the immediate aftermath of his rape of Vixen. (Some accounts of the scene might say it’s only ‘near-rape,’ but I should hope we all know better than that these days.) Naturally this is the most unpleasant scene in the film, particularly as Gavin’s horror is played out in every bit as extroverted a manner as her passion in earlier scenes, and there’s a very unsavoury overtone to it all as the connotation seems to be that Niles is giving Vixen the punishment she deserves for her bigotry toward him. Furthermore, when the two make peace in the final scene – one of only two moments in which Vixen addresses Niles by his real name, as opposed to ‘Rufus’ or ‘Sambo’ (the other time being out of fear, immediately prior to the rape) – we might take this to imply that the rape was a necessary and cathartic art for both parties. As unpalatable as this suggestion might be in 2018, we have to bear in mind that the world was a different place in 1968, and that Meyer and other exploitation filmmakers of the time tended to consider it an obligation to throw in a hint of Old Testament-style judgement on their sinful protagonists to give the films more of a fighting chance among religious audiences. And, as we noted already, the film stops short of giving Vixen the ultimate punishment which so often befell characters of her ilk at the time, and indeed in years since (take Gavin’s tragic lesbian character in Meyer’s later film Beyond The Valley of the Dolls).

We can scarcely fail to mention that Niles’ near-conversion to communism comes in the immediate aftermath of his rape of Vixen. (Some accounts of the scene might say it’s only ‘near-rape,’ but I should hope we all know better than that these days.) Naturally this is the most unpleasant scene in the film, particularly as Gavin’s horror is played out in every bit as extroverted a manner as her passion in earlier scenes, and there’s a very unsavoury overtone to it all as the connotation seems to be that Niles is giving Vixen the punishment she deserves for her bigotry toward him. Furthermore, when the two make peace in the final scene – one of only two moments in which Vixen addresses Niles by his real name, as opposed to ‘Rufus’ or ‘Sambo’ (the other time being out of fear, immediately prior to the rape) – we might take this to imply that the rape was a necessary and cathartic art for both parties. As unpalatable as this suggestion might be in 2018, we have to bear in mind that the world was a different place in 1968, and that Meyer and other exploitation filmmakers of the time tended to consider it an obligation to throw in a hint of Old Testament-style judgement on their sinful protagonists to give the films more of a fighting chance among religious audiences. And, as we noted already, the film stops short of giving Vixen the ultimate punishment which so often befell characters of her ilk at the time, and indeed in years since (take Gavin’s tragic lesbian character in Meyer’s later film Beyond The Valley of the Dolls). With such recent high profile success stories as It, A Quiet Place and Hereditary, the world at large is finally opening up to horror movies of a more sombre, introspective nature than the mainstream crowds tend to expect. Of course, anyone who keeps abreast of international indie horror and the festivals should already be well acquainted with the more understated and intellectual breed of genre material which seems to be the dominant horror format today, and The Dark – which screened earlier this year at London’s FrightFest and is now coming to UK home entertainment via Signature’s FrightFest Presents imprint – is the latest such horror release to fit that mould. On top of its slower pace and more grounded tone, The Dark is also similar to the aforementioned mainstream horror hits in that it largely focuses on young characters, in this case two teenagers who have both suffered horrifically at the hands of abhorrent adults, and come to find the familial bond they need in one another.

With such recent high profile success stories as It, A Quiet Place and Hereditary, the world at large is finally opening up to horror movies of a more sombre, introspective nature than the mainstream crowds tend to expect. Of course, anyone who keeps abreast of international indie horror and the festivals should already be well acquainted with the more understated and intellectual breed of genre material which seems to be the dominant horror format today, and The Dark – which screened earlier this year at London’s FrightFest and is now coming to UK home entertainment via Signature’s FrightFest Presents imprint – is the latest such horror release to fit that mould. On top of its slower pace and more grounded tone, The Dark is also similar to the aforementioned mainstream horror hits in that it largely focuses on young characters, in this case two teenagers who have both suffered horrifically at the hands of abhorrent adults, and come to find the familial bond they need in one another.

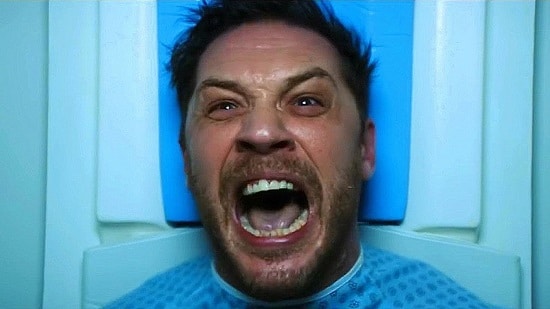

How does a film which, from its mere conception, is a blatant cash-in on other established properties go about making itself seem something more than the blatant cash-in it is? As soon as word got out that Sony had given the green light to a solo movie based around Spider-Man bad guy Venom, it was hard not to greet the news both with a sigh of exhaustion, and a furrowed brow of confusion; how could this character, inherently a shadowy reflection of Marvel’s iconic superhero, function in a film of his own in which Spider-Man himself would not appear (nor, as it turns out, even get the slightest mention)? And given the track record of comic book villains given their own standalone ventures – most notoriously 2004’s Catwoman – was it really the best idea?

How does a film which, from its mere conception, is a blatant cash-in on other established properties go about making itself seem something more than the blatant cash-in it is? As soon as word got out that Sony had given the green light to a solo movie based around Spider-Man bad guy Venom, it was hard not to greet the news both with a sigh of exhaustion, and a furrowed brow of confusion; how could this character, inherently a shadowy reflection of Marvel’s iconic superhero, function in a film of his own in which Spider-Man himself would not appear (nor, as it turns out, even get the slightest mention)? And given the track record of comic book villains given their own standalone ventures – most notoriously 2004’s Catwoman – was it really the best idea?

Jackie Chan, as anyone can tell you, pioneered the martial arts action comedy, punctuating awe-inspiring displays of physical daring and expertise with immaculate comic timing and irreverent sensibilities which have resonated with audiences worldwide for decades. From the late 1970s and well into the 80s, Jackie pumped out hit after hit in this format, several of which – notably

Jackie Chan, as anyone can tell you, pioneered the martial arts action comedy, punctuating awe-inspiring displays of physical daring and expertise with immaculate comic timing and irreverent sensibilities which have resonated with audiences worldwide for decades. From the late 1970s and well into the 80s, Jackie pumped out hit after hit in this format, several of which – notably  Plot-wise, I’ve pretty much said it all already: Jackie is

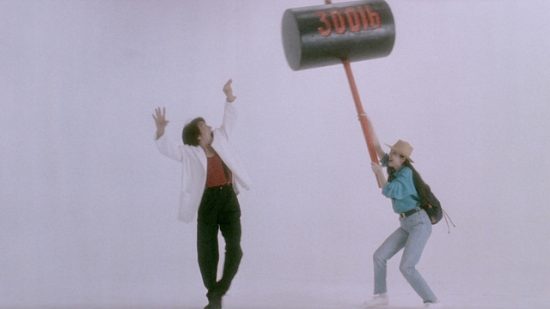

Plot-wise, I’ve pretty much said it all already: Jackie is  City Hunter is not without its plus points. As with any Jackie Chan movie, it keeps up a fast pace and packs in plenty of engaging action. Yet the film suffers heavily from a persistent sense of one-upmanship; Jackie’s persona and his body of work was already larger than life, and this film is attempting to be even larger than that. Whereas there’s an almost unassuming charm to some of Jackie’s earlier, smaller scale work, here the sledgehammer subtlety and relentless cartoonishness just gets exhausting, particularly when we get a gratuitous cheesy pop song and dance number midway, and – in what is, for better of worse, the film’s most memorable moment – a scene in which Street Fighter II, then at the peak of its popularity, literally comes to life. Your reaction to this scene – i.e., whether you find it hilarious or wince-inducing – might very well determine how you’ll feel about the film overall.

City Hunter is not without its plus points. As with any Jackie Chan movie, it keeps up a fast pace and packs in plenty of engaging action. Yet the film suffers heavily from a persistent sense of one-upmanship; Jackie’s persona and his body of work was already larger than life, and this film is attempting to be even larger than that. Whereas there’s an almost unassuming charm to some of Jackie’s earlier, smaller scale work, here the sledgehammer subtlety and relentless cartoonishness just gets exhausting, particularly when we get a gratuitous cheesy pop song and dance number midway, and – in what is, for better of worse, the film’s most memorable moment – a scene in which Street Fighter II, then at the peak of its popularity, literally comes to life. Your reaction to this scene – i.e., whether you find it hilarious or wince-inducing – might very well determine how you’ll feel about the film overall. Sequels and remakes have been a thing forever, but it’s only comparatively recently that the term ‘reboot’ was added to the cinematic vernacular. Admittedly, the line between this new-ish descriptor and the aforementioned established film categories is often hazy, but it would seem to effectively mean either taking the story and/or characters in question back to square one, or in some way reviving their story world for contemporary audiences in a way that doesn’t necessarily negate what went before. 2018 has had its share of high profile reboots: take the recently released

Sequels and remakes have been a thing forever, but it’s only comparatively recently that the term ‘reboot’ was added to the cinematic vernacular. Admittedly, the line between this new-ish descriptor and the aforementioned established film categories is often hazy, but it would seem to effectively mean either taking the story and/or characters in question back to square one, or in some way reviving their story world for contemporary audiences in a way that doesn’t necessarily negate what went before. 2018 has had its share of high profile reboots: take the recently released  Largely plotless, Death Kiss follows its unnamed, familiar-looking protagonist as he traverses streets and backwoods gang neighbourhoods, clad in various recognisable ensembles – shirt, tie and trench coat, thick woolly jumper and beanie hat – but always with a gun in his hand, and always showing up right when bloody retribution is called for. In between these vengeful vignettes, we cut to Daniel Baldwin (another actor who, if we’re being a bit mean, we might say owes a lot of his work to resembling other more famous stars) as an Alex Jones-ish radio host, ranting about how political correctness has gone mad, the police aren’t even trying to help us and so on and so forth, and pondering whether taking the law into our own hands might be the answer. Then we also cut away to a single mother (Eva Hamilton) and her wheelchair-bound daughter, who have just moved out to a secluded house in the country, but are unknowingly under the protection of a mysterious benefactor with a grizzled face and a striking moustache, although the hows, whys and wherefores of this are not immediately clear.

Largely plotless, Death Kiss follows its unnamed, familiar-looking protagonist as he traverses streets and backwoods gang neighbourhoods, clad in various recognisable ensembles – shirt, tie and trench coat, thick woolly jumper and beanie hat – but always with a gun in his hand, and always showing up right when bloody retribution is called for. In between these vengeful vignettes, we cut to Daniel Baldwin (another actor who, if we’re being a bit mean, we might say owes a lot of his work to resembling other more famous stars) as an Alex Jones-ish radio host, ranting about how political correctness has gone mad, the police aren’t even trying to help us and so on and so forth, and pondering whether taking the law into our own hands might be the answer. Then we also cut away to a single mother (Eva Hamilton) and her wheelchair-bound daughter, who have just moved out to a secluded house in the country, but are unknowingly under the protection of a mysterious benefactor with a grizzled face and a striking moustache, although the hows, whys and wherefores of this are not immediately clear. The gradual decline of the found footage horror movie is not entirely down to oversaturation. There are larger cultural reasons why the format doesn’t totally work anymore, the principle issue being that it’s just not as accurate reflection of our current video culture as it once was. The days of average joes lugging around camcorders, striving to capture every moment of their daily lives on Hi-8 are largely behind us (for which I suspect we should be thankful); today, most of us are more likely to present carefully staged and edited snippets of our lives in short clips shared across social media. Any more extended periods spent on camera are likely to be in face time or webcam chats, more than likely with other online platforms coming into play during this time… and this comparatively novel approach was applied to a horror scenario in 2014’s Unfriended, plus its recent sequel.

The gradual decline of the found footage horror movie is not entirely down to oversaturation. There are larger cultural reasons why the format doesn’t totally work anymore, the principle issue being that it’s just not as accurate reflection of our current video culture as it once was. The days of average joes lugging around camcorders, striving to capture every moment of their daily lives on Hi-8 are largely behind us (for which I suspect we should be thankful); today, most of us are more likely to present carefully staged and edited snippets of our lives in short clips shared across social media. Any more extended periods spent on camera are likely to be in face time or webcam chats, more than likely with other online platforms coming into play during this time… and this comparatively novel approach was applied to a horror scenario in 2014’s Unfriended, plus its recent sequel.