Tatsumi is a troubled young man. He doesn’t know what he wants to do with his life, and we first meet him at an abortive encounter with a careers guidance officer which sees him, exasperatedly, told to go back to his parents. Yet he doesn’t ask for their advice, either: instead, he withdraws from the world altogether, sitting in the dark in his room and watching old recordings of TV. And so this could easily have become a story about hikikomori, that phenomenon of the young Japanese men who hole up at their parents’ homes and shun any notion of independence, preferring instead to stay in their old bedrooms, hiding from the world. A Dobugawa Dream follows its story elsewhere.

Although Tatsumi says almost nothing, particularly at the beginning of the film, the audience is made aware of the source of his withdrawal. He’s haunted by the suicide of his closest friend, and he lacks the ability to enunciate his feelings about this trauma. And so, one day, he runs – something else he is ill-equipped to do, but run he does, finding himself alone and barefoot in a run-down part of town. Tatsumi is almost catatonic; he simply walks from place to place, encountering others who are like him – peripheral, outside the margins of polite, orderly society, tragicomic people with little rational response to their circumstances. When he crashes an unorthodox funeral service one night, following a group of itinerants following a makeshift procession, it turns out that the man they’re mourning isn’t quite dead. This ‘old man’, never called anything else by Tatsumi, takes the younger man under his wing almost by instinct, vouching for him and even saying that he is his son. Now, Tatsumi joins the ranks of those who have ‘nowhere to go’, well aside from the down-at-heel bar they often frequent. Gradually, this closed-off young man begins to verbalise, interact with the world again, and as we follow him, we begin to piece together the stories of the people around him – although the men don’t speak for themselves and their backgrounds are typically filled in by women. Redemption comes from odd places in this world, and its path is rarely straightforward, but at the heart of A Dobugawa Dream it’s issues surrounding memory, guilt and at a deeper level, masculinity which steadily come to the fore.

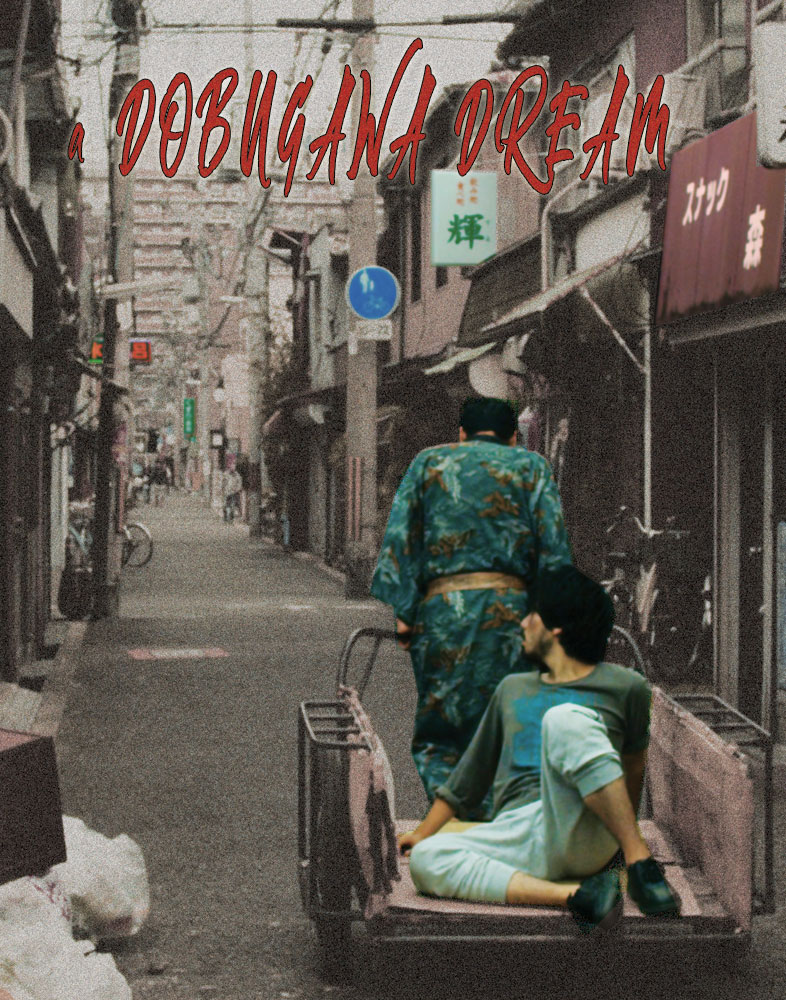

This is a Japan rarely seen by Western audiences, and so it comes as something of a surprise to see all of this squalor on screen. With the exception of Sion Sono’s Himizu (2011) and its post-tsunami shanty towns, I can’t recall a story taking place so entirely outside the clean, comfortable Japan usually presented to us. This is poverty, but primarily it’s poverty affecting people who have a variety of reasons for being where they are, clustering together on the periphery of regular life. The stories we glean are very different, but even for those which go unheard, there seems to be a common thread: how people cope, or fail to cope, when something or someone significant departs their life. The backdrop to this might be wretched, but the question remains valid. And there is absolutely no gloss here: most of the film’s frames are literally crammed with garbage. The symbolism seems fairly clear, but then this is a testament to poverty too, with people living side-by-side with garbage, beneath the notice of most. A Dobugawa Dream is almost eerily understated, leaving the audience to pick through this unsanitary setting to get to the key messages. If it reminds me of anything at all, it’s perhaps The Fisher King, another story of men thrown together by tragic circumstance on the outskirts of their own society, but the deliberate humour is absent in A Dobugawa Dream, although the slightly uncomfortable, bizarre charm is definitely intact. The film does delve into some odd absurdist tableaux too, though chiefly to illustrate just how far outside ‘reality’ its characters operate.

Subtle through and through, the film’s handling of closure and moving on is profoundly moving without any attempts to use sentimentalism to get there. With minimal dialogue and exposition, it manages to craft a very engaging and affecting story of sadness and guilt, approaching these obliquely but nonetheless effectively. There’s no high action. There’s no stirring speeches, but A Dobugawa Dream speaks for a hidden, taboo Japan and its inhabitants, particularly its broken men and what becomes of them. How the film concludes is a gentle, sensitive master stroke. This is a highly original piece of work.

A Dobugawa Dream will receive its international premiere at the Raindance Film Festival on 23rd September 2019. For tickets and further information, please click here.