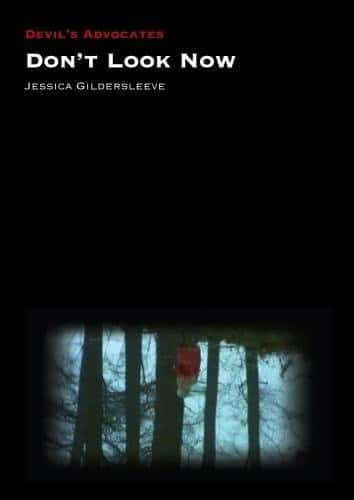

Don’t Look Now is a strange and rather wonderful horror film: routinely featuring on ‘best films of all time’ lists, it clearly made (and continues to make) a resonant impression on viewers, whether those who saw it upon release or those who have come to it later. It’s this lasting appeal which has prompted some serious consideration in print in recent years, with this edition of the Devil’s Advocates series by author Jessica Gildersleeve marking an upcoming addition to the fold.

Don’t Look Now is a strange and rather wonderful horror film: routinely featuring on ‘best films of all time’ lists, it clearly made (and continues to make) a resonant impression on viewers, whether those who saw it upon release or those who have come to it later. It’s this lasting appeal which has prompted some serious consideration in print in recent years, with this edition of the Devil’s Advocates series by author Jessica Gildersleeve marking an upcoming addition to the fold.

Gildersleeve argues that Don’t Look Now is remarkable, firstly, because it seems devoid of the tropes which characterise other, more notorious horrors of the 1970s. When it comes to horror cinema, the Seventies tend to be feted for films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Exorcist or Halloween, Gildersleeve argues – films which are spectacularly bloody, graphic or otherwise vivid assaults on the home. Don’t Look Now, although it may (to me) sound like another movie of the type mentioned above (one of the many ‘Don’t’ titles of the era) is altogether more subtle and restrained, at least for the most part. Whilst she acknowledges that the film can and does include shocking scenes, Gildersleeve’s opening gambit is that Don’t Look Now relies on the awful realisation of ‘knowing too late’, something which riffs on the breakdown of the modern family throughout.

Continuing with this, she suggests that horror can be particularly responsive to social anxieties – an idea which countless of us would no doubt agree with – and that Don’t Look Now was made at a particularly malleable time in history. Noting that whilst many of the tropes we now know and recognise were being developed in the Seventies, the film wasn’t overly expected to join forces with these, as things were still relatively new, experimental. However, the movement of horror from the crumbling Gothic castle to the modern urban setting allows Don’t Look Now to exploit particular pressures surrounding parenthood and belonging, in a contemporary sense.

Perhaps the main body of the book and its arguments, however, is devoted to the film’s specific treatment of trauma; this certainly isn’t your standard book which devotes a chapter to the director, then a chapter to the key actors, and so on. In order to retain her chosen focus, Gildersleeve uses something she refers to as ‘contemporary trauma theory’, and it’s at this juncture that the book really hikes up its academic tone. Of course, the Devil’s Advocates series tends towards the scholarly, granted, but I do feel that, in comparison with the last title in the series which I read, the discussion of Don’t Look Now on offer here is much more didactic. It also soon segues into an emphasis on psychoanalytical theory, a school of thought which – personal bias on the table here – I don’t find particularly enlightening, even if some interesting points are raised. Continuing the focus on trauma via discussions on repression, gender, othering and similar topics, the writing here is heavily referenced and footnoted throughout, which shows depth of analysis, but can make it slightly tougher in places to glean a sense of Gildersleeve’s own voice from amongst the parentheses.

Perhaps the main body of the book and its arguments, however, is devoted to the film’s specific treatment of trauma; this certainly isn’t your standard book which devotes a chapter to the director, then a chapter to the key actors, and so on. In order to retain her chosen focus, Gildersleeve uses something she refers to as ‘contemporary trauma theory’, and it’s at this juncture that the book really hikes up its academic tone. Of course, the Devil’s Advocates series tends towards the scholarly, granted, but I do feel that, in comparison with the last title in the series which I read, the discussion of Don’t Look Now on offer here is much more didactic. It also soon segues into an emphasis on psychoanalytical theory, a school of thought which – personal bias on the table here – I don’t find particularly enlightening, even if some interesting points are raised. Continuing the focus on trauma via discussions on repression, gender, othering and similar topics, the writing here is heavily referenced and footnoted throughout, which shows depth of analysis, but can make it slightly tougher in places to glean a sense of Gildersleeve’s own voice from amongst the parentheses.

However, the main gripe I have is that the discussion on offer becomes rather repetitive. Clearly the idea of trauma is fundamental to the book, but the same comments crop up. The author herself reiterates the phrase ‘as I have already shown’ in several places, which is a clear indication that material is being restated. For an example of the kind of repetition I mean: very similar comments recur about how the Venetian hotel occupied by the Baxters has been shut up, symbolising how the season is over and how unwelcome they seem to be. An interesting point, and this kind of repetition may be a deliberate tactic to affirm and reaffirm the author’s viewpoints, perhaps, but – as a lay reader – I would have preferred more breadth than depth, and not to have the same points being made.

However, close analyses of key scenes are very engaging indeed, with some interesting discussion of symbol and setting. Clearly, the book is well-researched and there is a huge range of further reading and viewing material in the bibliography, meaning that the book could lead onto other things. The book can also be read in a sitting: it’s helpfully chaptered and bite-size. Many aspects of the book render it useful and reader-friendly.

Certainly, readers who would appreciate a different, scholarly perspective on Don’t Look Now will find many rewards here, and completists who love the film will find a wealth of finer details, perhaps taking them into unforeseen directions. It may be preaching to the choir for many, but what we are seeing is a wealth of new commentators re-examining horror and finding it compelling for a whole host of new reasons, which is – by and large – refreshing to see.

Don’t Look Now (Devil’s Advocates) by Jessica Gildersleeve is now available to order via Auteur Publishing.