Frankenstein’s Creature is one of the true modern horror archetypes. Like the vampire or the ghoul, it’s an enduring and versatile monster, ready to reflect whatever set of anxieties we currently have; its ghastly stitched flesh and tendons are durable enough to withstand whatever we seek from it. And yet, unlike the vampire – which was popularised by literature and the likes of Le Fanu and Stoker later in the century, but existed in myth in various forms for centuries beforehand – this reanimated man made of men stems from the imagination of one person: a teenage girl, Mary Godwin, later Mary Shelley. Although she wrote throughout her life, it is Frankenstein for which she’s famous, and its legacy is quite unprecedented. And, as cinema developed, it was one of the first horror stories ever to be adapted for the screen, where it has returned in a wide array of forms over the past century.

Frankenstein’s Creature is one of the true modern horror archetypes. Like the vampire or the ghoul, it’s an enduring and versatile monster, ready to reflect whatever set of anxieties we currently have; its ghastly stitched flesh and tendons are durable enough to withstand whatever we seek from it. And yet, unlike the vampire – which was popularised by literature and the likes of Le Fanu and Stoker later in the century, but existed in myth in various forms for centuries beforehand – this reanimated man made of men stems from the imagination of one person: a teenage girl, Mary Godwin, later Mary Shelley. Although she wrote throughout her life, it is Frankenstein for which she’s famous, and its legacy is quite unprecedented. And, as cinema developed, it was one of the first horror stories ever to be adapted for the screen, where it has returned in a wide array of forms over the past century.

“What terrified me will terrify others…”

The circumstances behind this extraordinary story are by now quite well-known. A group of exiles from England – Mary included – arrived at a Swiss villa on the banks of Lake Geneva in the spring of 1816. The party consisted of Mary, her lover, the radical poet and atheist Percy Shelley, Mary’s stepsister (and both Shelley and Byron’s lover at times) ‘Claire’ Clairmont, the notorious Lord Byron, and his physician, John Polidori. A group of intelligent, educated people, at odds with their own society, found themselves together abroad, and frequently kept indoors by rain and storms which lashed the villa (this gathering itself has been the subject of a horror film – Gothic, directed by Ken Russell, so evocative has the thought of it all become). Eventually, after getting into the habit of sharing ghost stories by night, Byron proposed a competition: the inmates of the villa were to write ghost stories of their own.

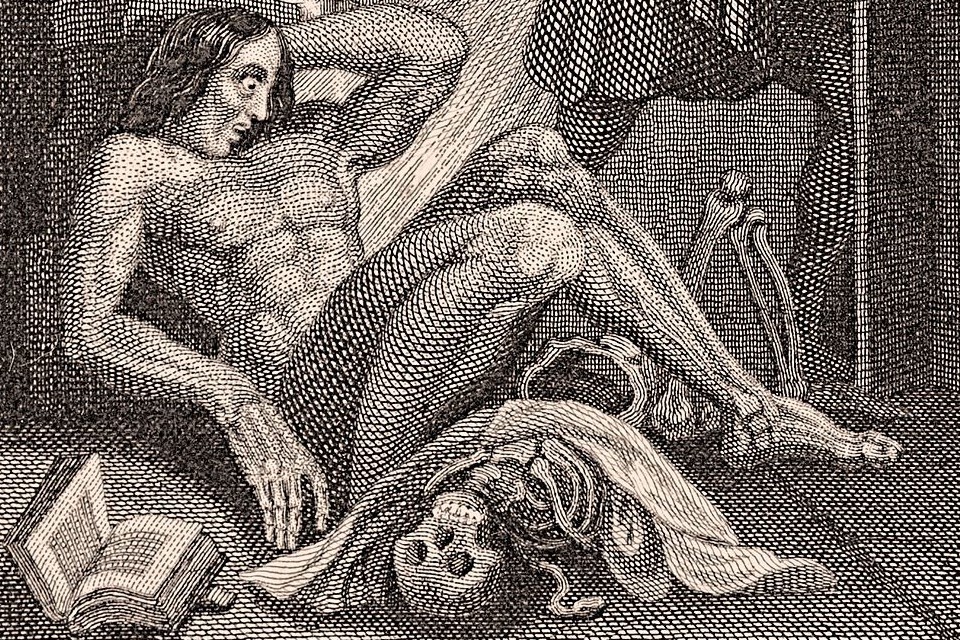

Mary initially agonised over this, struggling to find a subject, until a bizarre, conglomerate dream of all of the lofty topics they had taken to discussing, alongside the probable emotive effects of the ghost stories themselves, presented her with not quite a ghost story, but certainly an original idea imbued with elements of science fiction as well as more conventional scares. She finally saw in her mind’s eye, ” the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half-vital motion.” Thus the Creature was born.

The circumstances of this gathering at the Villa Diodati are of course interesting and relevant, but sometimes there’s a tendency to see this event in a sort of vacuum, forgetting all that had come before it and how this may have impacted upon the psyche of the precocious but very young girl who went on the pen the tale of Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus, which was completed as a full-length novel the following year, and published the year after. Even Shelley catches himself wondering, in an article for the Athenaeum in 1832 (after he had re-edited the book), “what could have been the series of thoughts – what could have been the peculiar experiences that awakened them – which conduced, in the author’s mind, to the astonishing combination of motives and incidents, and the startling catastrophe which compose this tale.” Possibly this is a rhetorical question, or perhaps he was simply not fully aware of the impact of the preceding years on Mary, because by the time she reached the villa, she had endured a whirlwind of events which were highly likely to have coloured her tale of creation gone awry.

“My hideous progeny…”

Mary Godwin met Shelley when she was just seventeen years old: he was an ardent disciple of her radical philosopher father, William Godwin. The younger man soon disappointed the expectations of the older; Mary and Percy fell in love, ‘staining’ his daughter’s reputation irrevocably, as Shelley was already married. The psychological impact of being a ‘fallen woman’ at this young age, shunned by polite society for decades to come, must have wounded this naturally bright, though naive girl. Shelley’s subsequent, immediate abandonment of his pregnant wife, Harriet, does him no credit (Harriet later committed suicide) and after the lovers had professed their ardent feelings for one another, the story goes that Mary lost her virginity in a churchyard soon thereafter.

An elopement to France followed, which had to be curtailed due to penury, and when Mary – pregnant, sick – returned to England, even her forward-thinking father would no longer assist her. Her first child was born prematurely in the following year, and died without even receiving a name. Plunged into a depression, Mary wrote in her journal of a “dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived.” Already in Mary’s life and in her imagination, even by the standards of the early nineteenth century, birth and death seem to be interlinked and interchangeable. Mary quietly bemoaned her frequent further pregnancies, complaining of how they stripped her of vital energy and health; only one of her children ever reached adulthood, and Mary nearly died of a miscarriage. Her own mother, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, had written to Godwin towards the end of her pregnancy with Mary that she expected “the animal” was about to be born; when the animal came, it left Mary Wollstonecraft with an acute infection which killed her within days. Doubtlessly, very female anxieties underpin the horrors of Frankenstein, just as much as anxieties about male-dominated science; the terrors of bringing new life in into the world do not start and end with Victor Frankenstein’s new methods.

An elopement to France followed, which had to be curtailed due to penury, and when Mary – pregnant, sick – returned to England, even her forward-thinking father would no longer assist her. Her first child was born prematurely in the following year, and died without even receiving a name. Plunged into a depression, Mary wrote in her journal of a “dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived.” Already in Mary’s life and in her imagination, even by the standards of the early nineteenth century, birth and death seem to be interlinked and interchangeable. Mary quietly bemoaned her frequent further pregnancies, complaining of how they stripped her of vital energy and health; only one of her children ever reached adulthood, and Mary nearly died of a miscarriage. Her own mother, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, had written to Godwin towards the end of her pregnancy with Mary that she expected “the animal” was about to be born; when the animal came, it left Mary Wollstonecraft with an acute infection which killed her within days. Doubtlessly, very female anxieties underpin the horrors of Frankenstein, just as much as anxieties about male-dominated science; the terrors of bringing new life in into the world do not start and end with Victor Frankenstein’s new methods.

“My workshop of filthy creation…”

In fact, Mary Shelley says more about the potential method for reanimating the Creature in her introduction than she has her protagonist, the brilliant, singular Victor Frankenstein, ever say in his own account – and she says very little herself. This idea of ‘the working of some powerful engine’ she describes, that idea which has furnished filmmakers with all manner of bizarre quasi-scientific scenes – sometimes the means overpower the ends in film – isn’t mentioned by Frankenstein. He says only that he has pieced his Creature out of materials from ‘charnel houses’, ‘the dissecting room’ and the ‘slaughter-house’ and then that, on one fateful day, he accomplishes his toils; there’s no mention of lightning, or amniotic fluid, or any of the other cinematic tropes which have steadily grown around interpretations of this rather mysterious process. The real horror comes with his success: suddenly, he sees the creature he has created as hideous – and abandons it. The Creature is to all intents and purposes a newborn who requires his basic needs to be met before he can begin to process language, which he does by imitation; in his later life, his outrage is against his ‘father’, the man who gave him life but rejected him outright, leaving him ill-equipped to manage the tumult of emotions and the thirst for revenge.

I’m sure that to a greater or lesser extent, Mary Shelley’s story was an oblique criticism of aspects of male behaviour, though perhaps as much as anything, the story is a warning about the arrogance of bending the world and its natural laws to human will. However, given that women did not yet have the right to attend university, and that a female protagonist could not feasibly have been placed in the situation in which Victor Frankenstein finds himself – remember, Elizabeth remains at home – Mary Shelley was still writing within and about the social order at this point. I don’t think it’s enough to say that Mary Shelley is simply warning of the perils of men, not women creating life: remember that Victor Frankenstein destroys the ‘mate’ he is making for the creature when he reflects that they could potentially then have children of their own, spawning a new, onerous type of humanity. In retaliation, the Creature strangles Victor’s new bride Elizabeth, circumventing the ‘happy family’ once again.

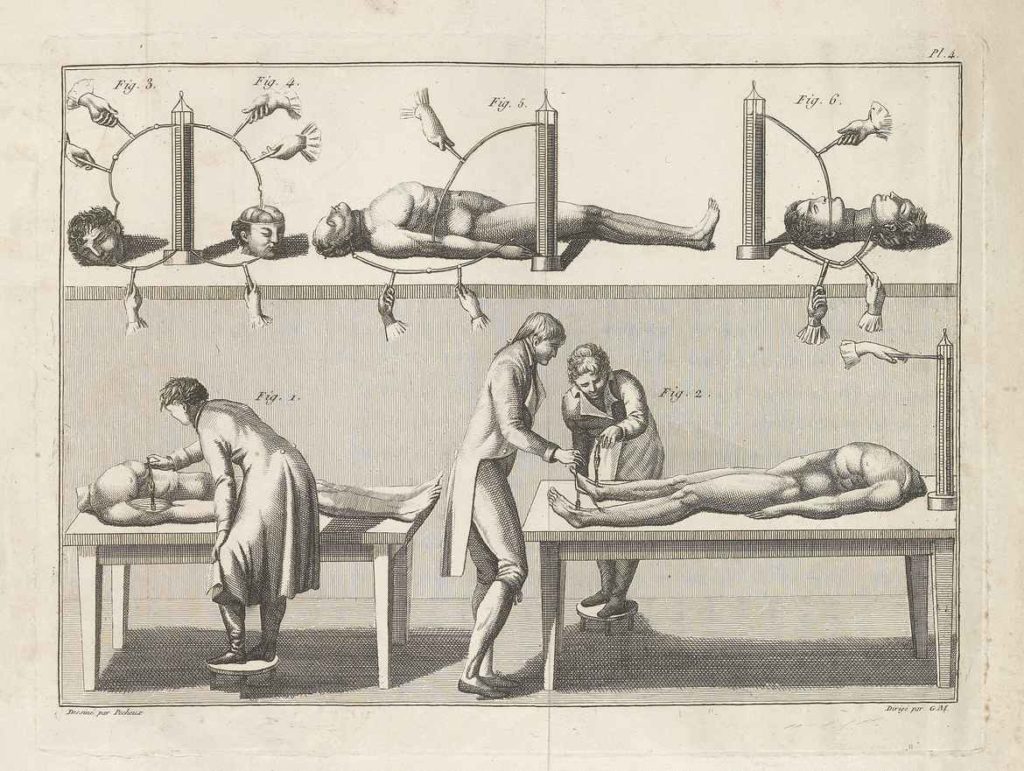

Whatever your interpretation of the story’s background, though, it’s clear that the early nineteenth century was fertile ground for a scientific horror story such as Frankenstein. The onward march of science on one hand – with experiments in galvanism, for instance, seemingly reanimating dead flesh – and the old hang-ups of superstition on the other, positions Frankenstein’s creature somewhere between the two. Mary Shelley herself speaks about galvanism, and was familiar with the pioneering works of Humphrey Davy and Erasmus Darwin, and listened to Byron and Shelley discussing what it takes to bestow life, and how this could be subverted. Science was moving forward in gigantic, intimidating leaps and bounds. But perhaps the most telling phenomenon which spanned the divide in real life was that of the ‘resurrection men’ or body-snatchers, who stole interred bodies from the hallowed ground of the churchyards for sale to men of science; it’s notable that Victor Frankenstein refers to himself as ‘a student of the unhallowed arts’ and possibly relies on these methods for himself.

There are many other reasons why Mary Shelley’s story has endured. A complex epistolary novel, it speaks to us of myriad other concerns which have stayed with us. Although it reaches for biblical interpretations – the idea of ‘playing God’, still of great interest in a Post-Enlightenment world – today, it perhaps affects a largely secular society more deeply in its themes of neglect and responsibility, prejudice against appearance and the consequences of ‘othering’. These concerns were present from the outset, too: rarely do other monsters of literature seem to seek nurture, and to weep when it transpires that no one is coming to them. Mina Harker may have had a moment’s concern for a creature ‘so hunted’ as Count Dracula, but it never approaches this sense of a child being abandoned.

“It’s alive! It’s alive!”

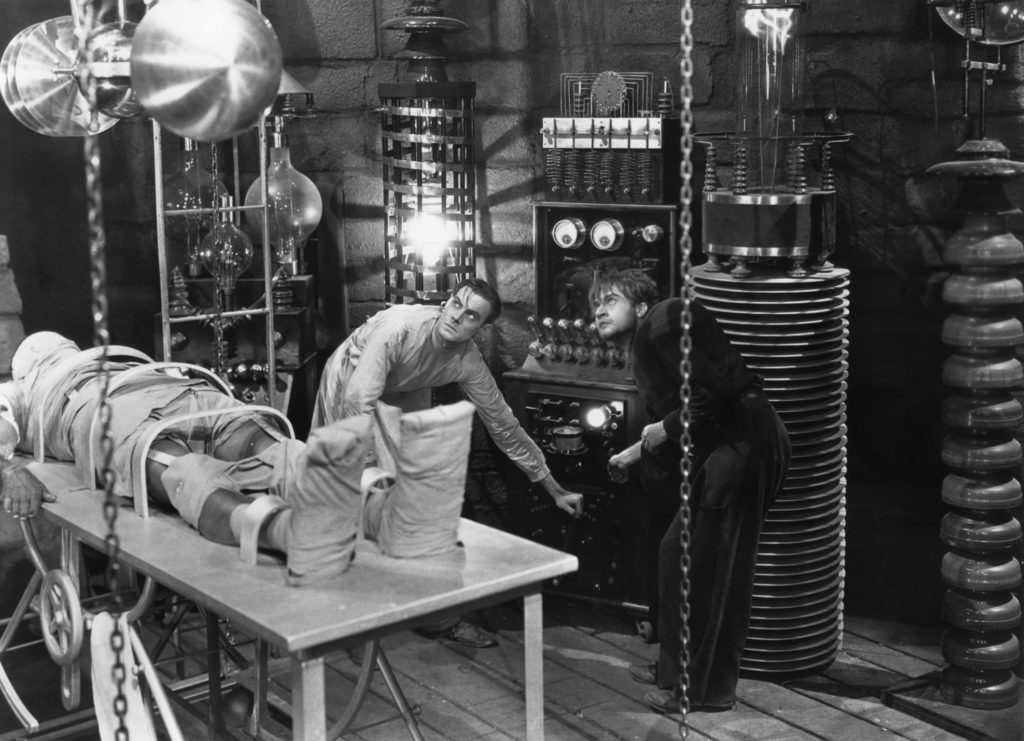

Horror cinema has at various times examined all of the themes above in different combinations, but one thing is true: filmmakers can’t quite bring themselves to wake the Creature quietly. The procedure itself seems to have become a key focus of Frankenstein on film from its very earliest inception, and the laboratory which harnesses the weather to generate electricity is as familiar to us as the standard-issue Frankenstein’s Creature established by Universal Studios. Even the very earliest short film – itself now over a century old – takes that approach (see below), and you could argue that James Whale puts more into the process than he does into the philosophical agony behind the process, which comes to the fore in the novel. Why this focus on the sparks flying? Why does Frankenstein himself start to wear something akin to a lab coat?

It seems to me that, once Frankenstein had started appearing on the new phenomenon of the cinema screen, both the novel and the new medium quickly became a distorting mirror for particularly twentieth century anxieties about twentieth century science. Universal Studio’s Frankenstein was released in 1931; by 1945, nuclear warfare would change world politics forever, and to this day ‘Frankenstein’ is an ongoing shorthand for worries about the direction science is heading – remember the ‘Frankenstein foods’ slur used against GM-crops when anxieties about this hit their peak about fifteen years ago? For early twentieth century viewers, with escalating world tensions, new methods of mass destruction and a constantly-refigured understanding of their place in the world, it seemed that monstrous things really did happen in labs. Frankenstein’s creature became a monster not of the ‘unhallowed arts’, but of bad science, and it’s a phenomenon which still recurs today.

It seems to me that, once Frankenstein had started appearing on the new phenomenon of the cinema screen, both the novel and the new medium quickly became a distorting mirror for particularly twentieth century anxieties about twentieth century science. Universal Studio’s Frankenstein was released in 1931; by 1945, nuclear warfare would change world politics forever, and to this day ‘Frankenstein’ is an ongoing shorthand for worries about the direction science is heading – remember the ‘Frankenstein foods’ slur used against GM-crops when anxieties about this hit their peak about fifteen years ago? For early twentieth century viewers, with escalating world tensions, new methods of mass destruction and a constantly-refigured understanding of their place in the world, it seemed that monstrous things really did happen in labs. Frankenstein’s creature became a monster not of the ‘unhallowed arts’, but of bad science, and it’s a phenomenon which still recurs today.

Select Filmography

Frankenstein (1910) – evidence of the urge to retell horrible or fantastical stories as soon as cinema became a possibility, this short film, released by the Eddison company, has a more redemptive ending than the book itself, but interestingly toys with the idea of the ‘creature’ as an other self.

The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) – following on from the introduction of Boris Karloff as ‘the creature’ in 1931, a performance (and make-up) which has crafted our image of the creature ever after, The Bride of Frankenstein is not only more bleak, but runs with the notion that the ‘monster wants a mate’, an idea which, in the novel, Victor rejects. In the film, it’s the female Creature who rejects the male creature, leading to one of his most despairing, poignant lines: “we belong dead!” The ‘new world of gods and monsters’ is a cruel place.

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) – it’s perhaps inevitable that Hammer Studios would get in on the act once their X-rated horror cinema came into being, and this film kick-started a number of Hammer interpretations of the source material, though seeing Peter Cushing as Frankenstein and Christopher Lee as the Creature is always a thrill.

Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) – imagine, if you will, Frankenstein being played by a German genre film superstar as a deranged Serbian nationalist hellbent on making an idealised male and female creature; add the veneer of incest and of course the glorious Joe D’Allesandro and you can truly fuck life in ze gall bladder, as Frankenstein implores us to do – in 3D! Often paired with director Paul Morrissey’s other camp interpretation of a horror classic – Blood for Dracula – and you have yourselves a good night lined up.

Frankenhooker (1990) – to go even further than the above: when a horror trope can be used as a joke, then it’s truly wormed its way into a culture, and director Frank Henenlotter plays fast and loose with it here, as a budding scientist reconstructs his sadly-deceased girlfriend (dead of a freak lawnmower accident) out of a horde of body parts retrieved from prostitutes who exploded after smoking contaminated crack. Now I see it written down that way, it seems more wrong than it looks on screen. I can’t help but wonder what Mary Shelley would have made of it.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) – we move full circle with this film, as this was represented as a close interpretation of the novel. To be fair, I think it’s a great film, even if Branagh can’t resist making himself the star and for bizarre reasons made himself a love interest. Robert De Niro, as the Creature, is both pitiable and execrable in the role, which is exactly how I read the character and which moves entirely away from the 1931 archetype, showing that there is still much scope for versatility in how the Creature can be interpreted.

Frankenstein’s Army (2013) – Nazis engineering super-soldiers out of body parts by using a certain Dr. Frankenstein’s journals to assist them? I think it would be rude not to, frankly. A daft and enjoyable piece of body horror, which has more in common with Henenlotter than it could ever have with Branagh.

Penny Dreadful (2014-16) – It’s easy to scoff at the trend for literary mash-ups – you know, the likes of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies – but Penny Dreadful, which shows us a Victorian London peopled with a whole host of famous literary monsters, is a triumph of interesting developments and love for the source material. Frankenstein’s Creature is played in the series by Rory Kinnear: his is an outstanding representation which brings us right back to the start. Kinnear’s creature is humane, intelligent and persecuted but utterly monstrous, tormenting his Creator and destroying his other work. However, Victorian London was awash with misfits and malformed, and the Creature escapes, seeking to build some sort of a life amongst others rather than fleeing for the wilderness. His subsequent association with the theatre is a fitting development, a final link between novel, screen and performance.

Penny Dreadful (2014-16) – It’s easy to scoff at the trend for literary mash-ups – you know, the likes of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies – but Penny Dreadful, which shows us a Victorian London peopled with a whole host of famous literary monsters, is a triumph of interesting developments and love for the source material. Frankenstein’s Creature is played in the series by Rory Kinnear: his is an outstanding representation which brings us right back to the start. Kinnear’s creature is humane, intelligent and persecuted but utterly monstrous, tormenting his Creator and destroying his other work. However, Victorian London was awash with misfits and malformed, and the Creature escapes, seeking to build some sort of a life amongst others rather than fleeing for the wilderness. His subsequent association with the theatre is a fitting development, a final link between novel, screen and performance.