I first encountered the cinema of Jean Rollin via the UK’s Redemption Films, whose founder, Nigel Wingrove, became good friends with Rollin over the years; the film company deserves far more awareness of the great service they did by bringing so many of these films into the common consciousness in the Nineties, making the films themselves into an artefact worth having with an array of stylish, distinctive video covers marking them out. Until that time, any knowledge I had of the director’s work came via still images in magazines, and there it probably would have stayed until, in all likelihood, the films resurfaced – though probably not as well-presented – during the earlier years of the DVD revolution, when there was a real surge of hitherto-unknown releases. But however the films may or may not have made their way to our shelves, it’s taken some time for Rollin criticism to follow in print, although Immoral Tales first re-assessed Rollin’s work in the nineties, and more recently, David Hinds published his Fascination: the Celluloid Dreams of Jean Rollin. But is there more to say?

I first encountered the cinema of Jean Rollin via the UK’s Redemption Films, whose founder, Nigel Wingrove, became good friends with Rollin over the years; the film company deserves far more awareness of the great service they did by bringing so many of these films into the common consciousness in the Nineties, making the films themselves into an artefact worth having with an array of stylish, distinctive video covers marking them out. Until that time, any knowledge I had of the director’s work came via still images in magazines, and there it probably would have stayed until, in all likelihood, the films resurfaced – though probably not as well-presented – during the earlier years of the DVD revolution, when there was a real surge of hitherto-unknown releases. But however the films may or may not have made their way to our shelves, it’s taken some time for Rollin criticism to follow in print, although Immoral Tales first re-assessed Rollin’s work in the nineties, and more recently, David Hinds published his Fascination: the Celluloid Dreams of Jean Rollin. But is there more to say?

Lost Girls: the Phantasmogorical Cinema of Jean Rollin has been very much promoted for its all-female authorship, something which I’ll admit I was surprised by: editor and writer, Samm Deighan, hasn’t exactly been a fan of promoting women-only agendas in the past, but publicity for Lost Girls has asserted that women are a minority in genre writing, deserving greater recognition. Well, everyone is free to change their minds of course, though this idea of a lack of ‘recognition’ doesn’t chime with my personal experience as both a woman and a writer, as I’ve said many times before. However, undoubtedly true is the fact that Rollin adored women, frequently making films from the perspective of female characters, and this is something else behind the rationale of Lost Girls -a female perspective on his uniquely female perspectives.

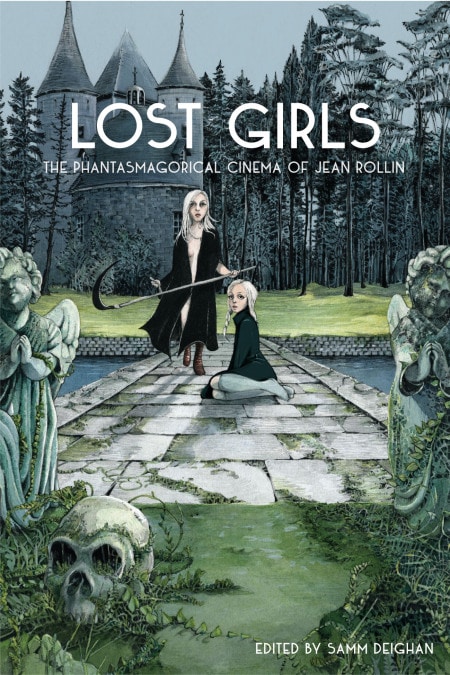

A brief foreword by actress Françoise Pascal (of The Iron Rose) is a pleasing addition here, and the book overall is attractive, heavily illustrated in colour and black & white with a custom artwork cover illustration. There are a variety of writers offering their views, and as the chapter titles might give away, the tone here is rather academic – though not to the extent of being inaccessible to the lay reader, and by and large all the chapters are clearly written, avoiding the cardinal sin of academic writing – incomprehensibility. However, links are forged between Rollin’s films and all manner of ideas; prepare to see his work linked to Nietzsche, Milton and Satan, to name but a few. Furthermore, the approach taken throughout the book is that Rollin was not about titillation, not featuring nudity for its own sake or to take pleasure in it on its own terms, but rather using female flesh in a range of pioneering ways, revolutionising tired tropes such as vampirism with his work. I’d be inclined to say that the truth lies somewhere between those two positions, personally. Yes, he was pioneering, but he also simply enjoyed filming and working with beautiful women, often coincidentally without a stitch on; I don’t think we do Rollin or his work any sort of disservice for acknowledging that. And lest we forget, Rollin also made pornography (though to be fair, Samm Deighan casts her eye over the likes of Anal Hospital in a chapter dedicated to Rollin’s ‘other’ films).

Happily, the book does far more than seek to reclaim Rollin as a proto-feminist. A large number of the essays in the book seek to re-position Rollin’s work by drawing parallels between it and other, comparable phenomena, such as 19th Century occultism. It’s an ambitious aspect of the book, and I certainly learned something; I hadn’t realised Rollin’s association with the poet Corbière, for example, so Marcelline Block’s study of the parallels between them was very enlightening. Alison Nastasi’s essay on The Iron Rose is also a definite high point in the book. A real sense of enthusiasm for the subject matter with an easy sense of knowledge combine to render something very readable (and the phrases “supernatural thrum” and “bellow of the human soul” are things of beauty.) The Iron Rose is an extraordinary film, a strangely gentle and barely-peopled story where a couple, trapped in a cemetery, confront the notion of their mortality via an erotic lens, and Nastasi captures this. Samm Deighan’s study of fairy tales is an engaging read, as is Virginie Sélavy’s detailed appraisal of Rollin’s use of castles in his films: whilst the same films are considered by separate writers, different aspects are explored.

I do have some issues with the book, however. Many of the essays carry the same message: that Rollin was a liberator of women by allowing his characters to escape the shackles of predatory male sexuality – often via a fantastical device (usually vampirism). To make this point, there is often a comparison made with existing vampire tropes in cinema. These comparisons perhaps unsurprisingly elevate Rollin, though sometimes at the expense of the older material. Promoting Rollin by rubbishing, as one example, Hammer seems unnecessary – as so frequently pointed out in Gianna D’Emilio’s opening essay on Le Viol du Vampire, they’re hardly comparable and dismissing Dracula Has Risen From The Grave as having an ‘antiquated Madonna-whore paradigm’ seems a rather heavy-handed dismissal; it’s perfectly possible to love and appreciate different takes on the vampire myth in cinema, and you don’t salvage the reputation of one film to the point of lionisation by knocking another.

There’s also a similar issue to the one I identified in Satanic Panic – a tendency to have the same information repeated, because several essayists each want to mention the same thing: for example, we read several times that vampirism is an alternative to bourgeois society, and then there is repetition of plot synopses throughout the chapters, but, also in common with Satanic Panic, perhaps reading the book from cover to cover isn’t the optimal approach to take and it’s better to just dip in from time to time.

This is certainly an unusual book with much to reward its readers, though it is very much in the feminist criticism category, which patently isn’t going to be for everyone. I don’t particularly feel that the much-vaunted women-only authorship has given rise to something which could never have been achieved with men on board, but what we do have here is a collection of interesting and ambitious essays on a unique filmmaker, academic in tone, but showcasing the genuine enthusiasm of the writers too.

You can pick up a copy of the book from Spectacular Optical here.