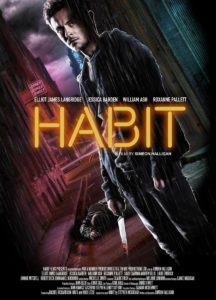

It’s always a privilege, in these social media-saturated times, to walk into a film screening without the faintest idea of what it’s all about. As I hadn’t even looked at the Celluloid Screams programme before we sat down to watch Habit (and as I almost immediately mix up titles and synopses anyway) it definitely felt like a boon that I had zero expectations, allowing the film to speak entirely for itself. I’m about to stop this being the case for anyone reading, though, by offering the barest of synopses here: Habit is a dark urban crime thriller which gradually adds horror elements, a claustrophobic and nightmarish tale which perhaps overstretches itself in some key regards, but still deserves credit for many of the things it does very well.

It’s always a privilege, in these social media-saturated times, to walk into a film screening without the faintest idea of what it’s all about. As I hadn’t even looked at the Celluloid Screams programme before we sat down to watch Habit (and as I almost immediately mix up titles and synopses anyway) it definitely felt like a boon that I had zero expectations, allowing the film to speak entirely for itself. I’m about to stop this being the case for anyone reading, though, by offering the barest of synopses here: Habit is a dark urban crime thriller which gradually adds horror elements, a claustrophobic and nightmarish tale which perhaps overstretches itself in some key regards, but still deserves credit for many of the things it does very well.

Mikey (Elliot James Langridge) is a bit of a harmless deadbeat, lurching from dole office (where he arrives late) to pub, to club, where he spends all the money he’s just been given and starts again. This all seems to stem from a traumatic childhood experience, a few moments of which we are shown in the opening scenes, but he and his older sister Amanda (Sally Carman) have remained close into adulthood, as much as she’s completely exasperated with his inability to sort himself out. A chance meeting one day throws him into the path of Lee (Jessica Barden), a teenage girl who seems to have nowhere else to go. She promptly installs herself in the life (and flat) of him and his housemate, and the pair soon grow closer.

One day, Mikey accompanies Lee on a visit to her uncle Ian (William Ash), which happens to be in a massage parlour down a dark side-street in Manchester’s city centre. Her uncle seems to be something of a wheeler-dealer, but he helps his niece out and takes an interest in Mikey. Mikey, in good part, takes a keen interest in one of the girls working there, and returns on his own later that night for a promised ‘special offer’. The night doesn’t quite go to plan, though, when he witnesses a violent attack on another man using the premises. Ian’s tactic is to bring Mikey into the fold, offering him a job as a doorman. Mikey needs the money, so he agrees, steadily growing closer to his employer and the rest of the staff in the process, whilst questioning what ‘family’ really means along the way.

Still, this isn’t exactly a legal establishment. Things are going on, and – gradually – Mikey has his eyes opened to what these things are.

Some strong and largely plausible performances allow Habit to generate a sensation of slowly-ratcheting tension, with particular praise here for Langridge, whose turn as an essentially decent young man adrift maintained my interest throughout. The gangland characters were believably menacing, and the dialogue overall did convey, in Mancunian accents, this idea of something bigger and more profoundly wrong going on behind the scenes. So far, so good. The Manchester sights and sounds may call to mind the kinds of gritty TV drama, or indeed the gritty comedy, for which the city is better-known, but that’s only to be expected – regional dialects often crop up this way in the media. I do have to pause on Jessica Barden’s portrayal of Lee though, while we’re on the topic of believability: her tones were a little too cut-glass to really believe she had grown up sofa-surfing in Greater Manchester, but then elements of her writing didn’t help her either – first she’s the innocent bystander whose uncle just wants to keep her out of the mucky business of prostitution, then in a heartbeat, she’s involved after all. Still, these issues didn’t stop me engaging with the film as such, although they gave me pause for thought.

There are plenty of other things which I unequivocally enjoyed about Habit. What’s certainly impressive about the film is how the rain-lashed Manchester nightscapes appear on screen. This is a strong visual feature in the film, with a variety of shots which really make the film feel firmly rooted in its Northern England environment. In some scenes the city looks bustling and alive; in others, the rundown old industrial buildings and dark corners look like something straight out of a dystopia. I’ve always felt like there’s something special about Northern cities with their ‘dark Satanic mills’, even if these mills have been refurbished and let out as plush apartments now. It’s somehow pleasing to see these places represented on screen, even if it’s not necessarily as somewhere relentlessly upbeat. God, where’s the interest in that, anyway?

Still, as much as this isn’t a straightforward horror yarn, it makes sense to talk about the horror that’s there. To give credit where credit’s due, I had suspected some sort of fantastical twist was coming, but the one that turned up wasn’t what I expected. This, in and of itself, is a plus, although the decision to take the film in an entirely new direction brings risks of its own.

The next two paragraphs could be considered a spoiler, so skip it if you want things to remain a complete surprise. I feel I have to mention the following, though, as the comparison to another film I’m about to make seems integral to a criticism I need to make about Habit.

I feel that the newer film owes many of its cues to We Are What We Are, whether the original or the (very competent) Jim Mickle ‘reimagining’ of same, which stayed fairly true to source. In We Are What We Are, the ‘ritual’ which united the loving, but clearly dysfunctional family unit was a surprise and a complication which eventually leads to their undoing; it’s a very, very similar case in Habit. The addition of this maybe-supernatural, definitely-deviant behaviour was, the first time I saw it, an interesting motif which has usually only made it to the screen in the form of mondo documentaries or what is as near to ‘classic’ exploitation cinema as we have, the likes of Ferox et al.

However, as engaging as this new treatment of the cannibalism theme is in We Are What We Are, it brings with it some issues. A little, even just a little more explanation would have benefited the film/s enormously; this doesn’t mean that all loose ends need to be tied up, but some of this would have added a deeper level of understanding for the characters and their motivations. Now, here is where someone on the Habit filmmaking team contacts me to tell me that none of them have even heard of We Are What We Are, so perhaps – perhaps – this may be pure coincidence, but to my mind, the issues which dog the older film cause some of the same issues in Habit. I’d like to know just that shade more about what motivates the characters, or how ‘the family’ were brought together in the first place. If their behaviour makes them feel alive in some new and exciting way, then why, and how does it do so? Admittedly, I don’t know the novel which Habit is based on – this may reveal far more, but going by the film alone is what many, if not most of the film’s viewers will be doing.

However, as engaging as this new treatment of the cannibalism theme is in We Are What We Are, it brings with it some issues. A little, even just a little more explanation would have benefited the film/s enormously; this doesn’t mean that all loose ends need to be tied up, but some of this would have added a deeper level of understanding for the characters and their motivations. Now, here is where someone on the Habit filmmaking team contacts me to tell me that none of them have even heard of We Are What We Are, so perhaps – perhaps – this may be pure coincidence, but to my mind, the issues which dog the older film cause some of the same issues in Habit. I’d like to know just that shade more about what motivates the characters, or how ‘the family’ were brought together in the first place. If their behaviour makes them feel alive in some new and exciting way, then why, and how does it do so? Admittedly, I don’t know the novel which Habit is based on – this may reveal far more, but going by the film alone is what many, if not most of the film’s viewers will be doing.

For all that this issue casts a slight shadow over the motivations of the characters in the film, however, I did enjoy the escalating nastiness of Habit. It’s now that I come to write my review that I realise how much I did enjoy it, actually. Ultimately it’s all about belonging, and the savage things people will participate in to feel that. It also touches on a very real source of horror – the ways in which people on the fringes of society can simply disappear without trace – and as such, it riffs on the idea of consumption in a brutal and visceral way.