By Nia Edwards-Behi and Keri O’Shea

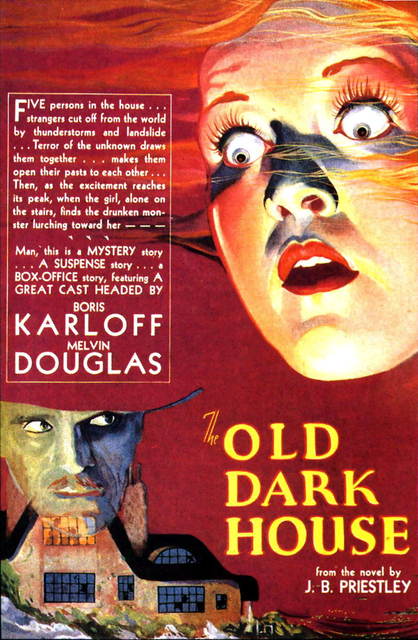

Keri: When Universal Pictures set about cementing the developing horror genre with a series of tales – both old and embellished – the small country of Wales, in the United Kingdom, was oddly integral to this process. The ‘Old Dark House’ (1932) was set in deepest, darkest Wales, the rain lashing, forcing the house’s inmates to stay put until escape was possible; The Wolf Man (1941), which spawned a new horror archetype, silver bullets and all, saw its central character get ‘the bite’ in Wales, before running amok through its landscapes. Why was Wales, a country which has – let’s be fair – struggled to gain recognition as a country in its own right, chosen as the backdrop for these American productions? Was it just remote enough to serve a purpose?

Keri: When Universal Pictures set about cementing the developing horror genre with a series of tales – both old and embellished – the small country of Wales, in the United Kingdom, was oddly integral to this process. The ‘Old Dark House’ (1932) was set in deepest, darkest Wales, the rain lashing, forcing the house’s inmates to stay put until escape was possible; The Wolf Man (1941), which spawned a new horror archetype, silver bullets and all, saw its central character get ‘the bite’ in Wales, before running amok through its landscapes. Why was Wales, a country which has – let’s be fair – struggled to gain recognition as a country in its own right, chosen as the backdrop for these American productions? Was it just remote enough to serve a purpose?

It’s because, I’d argue, it’s a landscape which is just on the border between modern and predictable and the somehow strange, unknown. It’s part of the United Kingdom, one of the wealthiest union of countries in the world, and it’s predominantly English-speaking, whether first or second language, but it’s still an outlier, a mystery, home to an ancient language, a country with a rich tradition of cultural practices which are distinct from those of its neighbours. The presence and promotion of the Welsh language (Cymraeg) still seems to be a source of discomfort to many (often monoglot English) commentators. Just a couple of weeks ago, a debate on bilingual schooling in Wales gave rise to many angry and baffled voices which could not countenance Welsh as a medium, despite there never being any indication that the lingua franca of English was being replaced. Somehow, having a parallel language on the doorstep is seen as worrisome and negative.

Wales also has a history of social protest and insurrection, which perhaps has some perhaps troubling pagan overtones – maybe prompting the question – how well does one know one’s neighbours? Welsh protest moments are, by any accounts, a strange phenomenon. The ‘Scotch Cattle’ of the early 1800s blended theatricality with real menace. Consisting of groups of men unhappy with their treatment at the hands of bosses or colleagues, they would gather at night for what were called ‘midnight terrors’, often wearing animal skins, blackened faces, with some blowing horns and many bellowing like cattle. This was intended to intimidate, and no doubt, it worked. The Cattle would damage property and machinery if they felt it was necessary to their aims, and they sent dramatic warnings to their peers – often written in animal’s blood. A message left as a warning to blacklegs (strike-breakers) stated, after naming the men responsible, “we are determined to draw the hearts out of all the men above named, and fix two of the hearts upon the horns of the Bull…we know them all. So we testify with our blood.”

Wales also has a history of social protest and insurrection, which perhaps has some perhaps troubling pagan overtones – maybe prompting the question – how well does one know one’s neighbours? Welsh protest moments are, by any accounts, a strange phenomenon. The ‘Scotch Cattle’ of the early 1800s blended theatricality with real menace. Consisting of groups of men unhappy with their treatment at the hands of bosses or colleagues, they would gather at night for what were called ‘midnight terrors’, often wearing animal skins, blackened faces, with some blowing horns and many bellowing like cattle. This was intended to intimidate, and no doubt, it worked. The Cattle would damage property and machinery if they felt it was necessary to their aims, and they sent dramatic warnings to their peers – often written in animal’s blood. A message left as a warning to blacklegs (strike-breakers) stated, after naming the men responsible, “we are determined to draw the hearts out of all the men above named, and fix two of the hearts upon the horns of the Bull…we know them all. So we testify with our blood.”

The so-called Rebecca’s Daughters also challenged the social order in a theatrical manner, this time wrecking and burning the tollgates designed to generate income on Welsh roads, at the expense of many of the poorest in society. Dressing as women, led by a ringleader – ‘Rebecca’ – these men turned their actions into something of a dramatic performance, complete with a script. Surely, on some level this kind of history fed into the film Darklands (1996), albeit the film chose to explore cult consciousness rather than straightforward protest. Even the name, ‘Darklands’, corresponds with the so-named ‘Black Domain’ in South Wales, where many of the protest movements mentioned above took place, and in this film the amassed strangers with their rituals seem to call to that strand of Welsh history.

The so-called Rebecca’s Daughters also challenged the social order in a theatrical manner, this time wrecking and burning the tollgates designed to generate income on Welsh roads, at the expense of many of the poorest in society. Dressing as women, led by a ringleader – ‘Rebecca’ – these men turned their actions into something of a dramatic performance, complete with a script. Surely, on some level this kind of history fed into the film Darklands (1996), albeit the film chose to explore cult consciousness rather than straightforward protest. Even the name, ‘Darklands’, corresponds with the so-named ‘Black Domain’ in South Wales, where many of the protest movements mentioned above took place, and in this film the amassed strangers with their rituals seem to call to that strand of Welsh history.

There are other historical practices in Wales that seem to call to a pagan past: the ceffyl pren (‘wooden horse’) was yet another way to bring down the wrath of the community upon any transgressors – by literally affixing them to a wooden frame in some cases, or more often, publically burning an effigy of them. Then, there’s the Mari Lwyd, a (frankly terrifying) midwinter practice where a shrouded horse skull is carried door to door by a bearer and a band of performers, where, to gain entrance into the homes they visit, a singing competition takes place. Whilst well-intentioned (and similar practices take place in other parts of Northern Europe) this is one vision which definitely has as much potential to scare as to entertain. Even if you expect to see a seven-foot bipedal horse creature at the door, it’s bound to be a bit of a shock. On occasion, by the way, this particular tradition still takes place at Christmas in Wales.

A historically strong sense of community, a sense of justice that can sometimes lash out at others and a love of shocking theatricality: these are things that seem to unite the Welsh throughout documented history, and they are also key components in many seminal folk horror films. So why, then, have there been so few Welsh horror films since the country’s name was invoked by Universal in the early decades of the twentieth century – much less folk horrors? Sure, the ‘Celtic Revival’ of the late nineteenth century no doubt helped to stop lots of the old practices and customs from slipping away entirely, but even aside from any historical precedents, there’s an absolute wealth of Welsh folklore which has yet to see the light of day.

The Mabinogion and New Welsh Folk tales

Nia: Wales’ most famous myths, The Mabinogion, have been the basis for a number of other, usually fantasy, works of art over the years, even including a South Korean MMORPG. The Mabinogion are a wide series of tales, written first in the 11th or 12th century and drawing upon the oral tradition of storytelling from much, much earlier. The tales are arranged into four ‘branches’, with characters appearing in various stories and the histories intertwining. The Mabinogion are the earliest examples of prose recorded in the literature of Britain, so to say that they are ‘folk’ is to under-state things.

It seems quite strange that while Wales has managed to take advantage of the whole Scandi-noir thing with its own take on the subgenre, TV series Y Gwyll/Hinterland, that we’ve yet to take advantage of Game of Thrones fever with a venture into the Mabinogi. While these tales are most obviously suited to the fantasy genre, there are some truly horrific elements to them that are absolutely ripe for the picking, either in direct adaptation or in more imaginative modern interpretations. There have been plenty of literary re-imaginings of The Mabinogion, such as the ‘New Stories from the Mabinogion’ series by Seren Books, but we’ve yet to see (to my knowledge) something like this taking place on screen, and certainly not the big screen. Perhaps the most famous tale of all, that of Branwen, features, in its climactic battle, a hideous construction, namely y pair dadeni, or the resurrection cauldron. That’s right, on a battlefield in Ireland, dead soldiers are flung into a cauldron and revived…where’s the medieval battle zombies film version of that?!

Branwen might be primarily tragic romantic history, but there are some profoundly horrific elements to it that would make for riveting – and entertaining – viewing. Likewise, there is some phenomenal body horror in characters such as Blodeuwedd, a woman created from flowers, a character whose ultimate fate some may vaguely know via Alan Garner’s The Owl Service and the subsequent television series. Blodeuwedd is the most famous example, but there are many other transfigurations from man to beast, such as the brothers turned into mating pairs of animals for three years by their vengeful uncle. Cripes.

Branwen might be primarily tragic romantic history, but there are some profoundly horrific elements to it that would make for riveting – and entertaining – viewing. Likewise, there is some phenomenal body horror in characters such as Blodeuwedd, a woman created from flowers, a character whose ultimate fate some may vaguely know via Alan Garner’s The Owl Service and the subsequent television series. Blodeuwedd is the most famous example, but there are many other transfigurations from man to beast, such as the brothers turned into mating pairs of animals for three years by their vengeful uncle. Cripes.

It’s been refreshing, then, that the best examples of recent Welsh genre filmmaking have drawn on notions of folk, while not relying on the Welsh mythological tradition. Perhaps indeed it’s because of the familiarity of tales like those of The Mabinogion that they’ve been avoided for so long, even in adaptation. The benefit of that is that when rare Welsh (and I mean culturally Welsh, you know, not just made in Wales) genre films come along they tend to be imaginative and interesting for it.

Director Chris Crow has a track record for imbuing his filmmaking with a sense of history and his most recent feature, The Lighthouse, is a really magnificent example of what can be achieved with notions of folk. By no means a traditional folk horror film, The Lighthouse draws on a singular moment in Welsh history and enlivens it with a tremendous sense of time, place and identity. The two men, trapped in the lighthouse in question, could well represent a rather traditional idea of the Welsh psyche befitting its period setting – God-fearing and self-loathing. Another recent example is Yr Ymadawiad (The Passing), a Welsh-language film which very strongly draws on Welsh history and landscape in such a wonderful way that to say too much rather spoils the film.

Director Chris Crow has a track record for imbuing his filmmaking with a sense of history and his most recent feature, The Lighthouse, is a really magnificent example of what can be achieved with notions of folk. By no means a traditional folk horror film, The Lighthouse draws on a singular moment in Welsh history and enlivens it with a tremendous sense of time, place and identity. The two men, trapped in the lighthouse in question, could well represent a rather traditional idea of the Welsh psyche befitting its period setting – God-fearing and self-loathing. Another recent example is Yr Ymadawiad (The Passing), a Welsh-language film which very strongly draws on Welsh history and landscape in such a wonderful way that to say too much rather spoils the film.

If there’s one thing to be said for these films, as much as I like them, it’s that they’re rather coy about the horror elements, and while I’m all for pushing genre boundaries, I’m also very much for witches and magic and creatures and otherworlds. It’s given me quite a thrill to see the project Cadi, formerly known as Gwrach (that’s ‘witch’ in Welsh), selected for this year’s round of Cinematic productions, the scheme that also brought us The Lighthouse. There’s scant detail so far, as expected of a film in pre-production, but it’s set in the present day, so I’m certainly excited. As genre productions in Wales seem to be on the rise, I can only hope that soon we’ll be turning to our mythology for some more horrific inspiration.