Idylls are not idylls in the British folk horror world, and the land itself hides a multitude of sins – even if ‘sins’ are a relatively modern phenomenon, by its standards. This small, but significant sub-genre derives a great deal of its power by examining the deep unease generated by Britain’s ancient history: the palpable, unshakeable sense that there is more out there to know than we currently do. Moreover, whilst the fear of insularity and pagan old ways jarring against the modern is integral, often the mysteries of the soil itself lead people astray. Something breaks out from beneath their feet; people fall under its sway, or they fight for rationality, but they must fight – against the forces of Nature and their representatives, the old gods.

“GROWS THE SEED AND BLOWS THE MEAD, AND SPRINGS THE WOOD ANEW…”

No film better understood (or embodied) the idea that you could quite literally unearth an evil than The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971). In this seminal film of its kind, it’s the process of ploughing the land which turns up something unexpected – the remains of something ungodly. This simple act, in a fraught rural agrarian society, pushes the whole of that society to the edge of a precipice, as the village’s young people begin to fantasise about the remains and turn away from their fraught relationship with the Church towards more carnal forces. (The Church’s shortcomings are also explored in another contemporary film now held up as canon in folk horror tradition, Witchfinder General). It’s interesting that, in her book, Looking For The Lost Gods of England, author Kathleen Herbert identifies two things which are relevant to The Blood on Satan’s Claw. Firstly, the age-old importance of the soil in pre- or very early Christian times, where it was seen as a conduit between man and god, and secondly, accounts of rituals which incorporated the plough as a means of making offerings to the land – by literally ploughing offerings to the gods into the dirt. The spectres of these practices were retained by early Christianity, though – typically – shorn of any pagan significance. In The Blood on Satan’s Claw, the camera acknowledges the importance of the soil, and a deliberate decision was taken to place the camera on ground level or even beneath the level of the dirt. This tactic gives the land a prescience and a menace, which is borne out by later events – the accidental discovery of physical, but supernatural remains.

No film better understood (or embodied) the idea that you could quite literally unearth an evil than The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971). In this seminal film of its kind, it’s the process of ploughing the land which turns up something unexpected – the remains of something ungodly. This simple act, in a fraught rural agrarian society, pushes the whole of that society to the edge of a precipice, as the village’s young people begin to fantasise about the remains and turn away from their fraught relationship with the Church towards more carnal forces. (The Church’s shortcomings are also explored in another contemporary film now held up as canon in folk horror tradition, Witchfinder General). It’s interesting that, in her book, Looking For The Lost Gods of England, author Kathleen Herbert identifies two things which are relevant to The Blood on Satan’s Claw. Firstly, the age-old importance of the soil in pre- or very early Christian times, where it was seen as a conduit between man and god, and secondly, accounts of rituals which incorporated the plough as a means of making offerings to the land – by literally ploughing offerings to the gods into the dirt. The spectres of these practices were retained by early Christianity, though – typically – shorn of any pagan significance. In The Blood on Satan’s Claw, the camera acknowledges the importance of the soil, and a deliberate decision was taken to place the camera on ground level or even beneath the level of the dirt. This tactic gives the land a prescience and a menace, which is borne out by later events – the accidental discovery of physical, but supernatural remains.

If something is unleashed simply via turning the land over, then what happens when something is deliberately placed in the ground? The master of quiet English horror, M. R. James, grappled with these possibilities in some of his best short ghost stories: he fills his tales with barely-tangible ancient terrors, which creep into view (almost) when modern interventions permit them. Some of these are summoned, accidentally or otherwise; some are malign entities which simply take their moment to escape. There are a number of stories which process these fears. In An Episode of Cathedral History – bearing in mind that cathedrals were often built on sites which formerly had other, pre-Christian ritual purposes – the tale tells of a mysterious tomb, whose disturbance causes strange phenomena to occur in the town and (possibly) releases a supernatural force, a ‘lamia’ – a term meaning a monster, or a witch. Whatever the creature is, it’s certainly something which Christianity would prefer locked safely away in hallowed ground (and there, we have the idea that the dirt of the earth can be sanctified with a Christian blessing, which speaks volumes to the beliefs of the past.) Perhaps the most famous James story, however, apart from ‘Oh Whistle and I’ll Come To You’, is A Warning to the Curious; the unearthing a Saxon crown, buried in the earth for the protection of the land, leads to severe repercussions for the amateur archaeologist who digs it up. Albeit in a simplified form, A Warning… was filmed as part of the superb A Ghost Story for Christmas series in the 1970s, as one of several Jamesian yarns adapted for television. The sense of a something relentless, a portent of doom, is married perfectly to a sense of the dispassionate, but harmful British terrain.

If something is unleashed simply via turning the land over, then what happens when something is deliberately placed in the ground? The master of quiet English horror, M. R. James, grappled with these possibilities in some of his best short ghost stories: he fills his tales with barely-tangible ancient terrors, which creep into view (almost) when modern interventions permit them. Some of these are summoned, accidentally or otherwise; some are malign entities which simply take their moment to escape. There are a number of stories which process these fears. In An Episode of Cathedral History – bearing in mind that cathedrals were often built on sites which formerly had other, pre-Christian ritual purposes – the tale tells of a mysterious tomb, whose disturbance causes strange phenomena to occur in the town and (possibly) releases a supernatural force, a ‘lamia’ – a term meaning a monster, or a witch. Whatever the creature is, it’s certainly something which Christianity would prefer locked safely away in hallowed ground (and there, we have the idea that the dirt of the earth can be sanctified with a Christian blessing, which speaks volumes to the beliefs of the past.) Perhaps the most famous James story, however, apart from ‘Oh Whistle and I’ll Come To You’, is A Warning to the Curious; the unearthing a Saxon crown, buried in the earth for the protection of the land, leads to severe repercussions for the amateur archaeologist who digs it up. Albeit in a simplified form, A Warning… was filmed as part of the superb A Ghost Story for Christmas series in the 1970s, as one of several Jamesian yarns adapted for television. The sense of a something relentless, a portent of doom, is married perfectly to a sense of the dispassionate, but harmful British terrain.

More recently, in film, The Fallow Field (2009) returns to the horrors of the soil, providing us with one character, Calham, who owns a farm and is the only person who truly understands his fields’ bizarre and disturbing yield, though keeping his secrets until almost the film’s close. Similarly, in Wake Wood (also 2009) pagan rituals come at a price, allowing a grieving family some time with a ‘rebirthed’ lost child who returns from the grave, but binding them to the land with various edicts – else their beloved daughter will be changed, irrevocably. Alright, this is an Irish film rather than British, but many of the plot elements overlap with other, older folk horrors, particularly the close-knit community whose alpha male acts as a custodian for the sinister magic being employed by the villagers.

This brings us up to The Borderlands (2013), a found-footage style folk horror which isn’t served particularly well, in my opinion, by this ubiquitous shakycam approach, but which introduces some good ideas about the ‘lie of the land’ and what lurks within it. It’s another film where the new God bumps head with the old, as the Vatican explores a secluded church in the Devon countryside. It transpires that the church is built on an old pagan site and that the local community is well-versed in ungodly practices, but the film goes further than that, making the land beneath the church a sentient character in its own right. In this respect, it’s a film reminiscent of The Ten Steps (2011), a brilliantly-economical horror short where a young girl’s fear of the basement means her parents – out at dinner while she’s home alone during a power cut – guide her down the ten steps to the meter in the dark, so she can get the lights back on. However, her descent doesn’t end at ten steps…

The clay can work wonders: it can manipulate people, birth terrors, and remind us all that the old gods hold sway. Perhaps we’re slower to see the significance of the soil in one of the folk horror classics, The Wicker Man (1973). Many of the elements we associate with the sub-genre are of course there – the pagan practices, the closed community and the threat to Christian outsiders, but at its heart, The Wicker Man is as a tussle between science and unreason, with the land of Summerisle itself at the kernel of the clash. The film only really discusses this element at its close. Howie, as he pleads for his life, has a moment where he invokes rational scientific argument to attempt to dissuade Lord Summerisle from doing what he’s about to do. The crops have failed, he points out, because the soil on the remote Scottish island is completely unsuited to growing apples – gulf stream or not. They were bound to fail.

The clay can work wonders: it can manipulate people, birth terrors, and remind us all that the old gods hold sway. Perhaps we’re slower to see the significance of the soil in one of the folk horror classics, The Wicker Man (1973). Many of the elements we associate with the sub-genre are of course there – the pagan practices, the closed community and the threat to Christian outsiders, but at its heart, The Wicker Man is as a tussle between science and unreason, with the land of Summerisle itself at the kernel of the clash. The film only really discusses this element at its close. Howie, as he pleads for his life, has a moment where he invokes rational scientific argument to attempt to dissuade Lord Summerisle from doing what he’s about to do. The crops have failed, he points out, because the soil on the remote Scottish island is completely unsuited to growing apples – gulf stream or not. They were bound to fail.

The inhabitants of Summerisle have built an industry on something very tenuous, and in their efforts to maintain their industry they are driven to sacrifice life to the ‘old gods’ so encouraged by their feudal Lord. Class and economics are at the forefront of this story, whatever the invocations to gods of the sea and land, and at the heart of it all is a poor soil, which cannot sustain what the community wants from it, regardless of the gods, old or new, being invoked.

SYLVAN FAMILIES

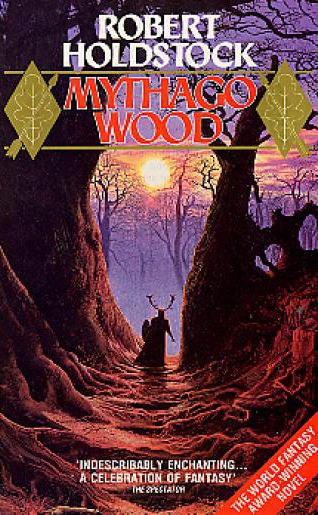

As well as what’s happening below the soil, the trees and structures on top of it have also figured significantly in folk horror. Woodland – which once covered huge swathes of the British Isles – has long been the stuff of nightmares, but it perpetuates British cultural identity, too: most children still know the stories of Sherwood Forest, for instance – an area that is still around today, though greatly depleted. Taking this link further still, the novel Mythago Wood (1984) encapsulates the idea that ancient woodland embodies our history: the woodland described here is a parallel universe, inhabited by archetypes of the British consciousness, from Celts to knights, through to monsters and magic. This can be a thrilling place, but it can also be menacing.

As well as what’s happening below the soil, the trees and structures on top of it have also figured significantly in folk horror. Woodland – which once covered huge swathes of the British Isles – has long been the stuff of nightmares, but it perpetuates British cultural identity, too: most children still know the stories of Sherwood Forest, for instance – an area that is still around today, though greatly depleted. Taking this link further still, the novel Mythago Wood (1984) encapsulates the idea that ancient woodland embodies our history: the woodland described here is a parallel universe, inhabited by archetypes of the British consciousness, from Celts to knights, through to monsters and magic. This can be a thrilling place, but it can also be menacing.

The menacing woods are of course a staple of horror, and today the ‘cabin in the woods’ probably qualifies as a new folklore, known as it is to so many. Interestingly, films like Pumpkinhead (1988) and more recently, The Witch (2015) are set in North America, but show that Old World threats and beliefs accompanied British and other European settlers when they emigrated there. The witchcraft being used in each of those films bears parallels to anxieties about witchcraft already long-familiar in Britain and Northern Europe. The Witch is a particularly telling example of folk horror, where the settlers are (probably?) persecuted by malign forces, practicing witchcraft in ways Christians of that era would recognise and dread. Perhaps the people who spring from the soil take their terrors wherever they go. And, as an aside, the description given of the ‘Blair Witch’ by an interviewee in the ground-breaking (pun noted) found footage horror/’documentary’ The Blair Witch Project (1999) sounds an awful lot like the creature which escapes from the cathedral tomb in M. R. James’s Episode of Cathedral History…

Part Two of The Soil Knows is coming soon…