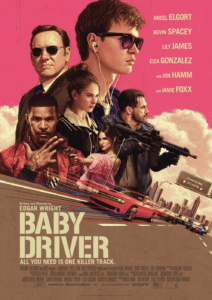

Edgar Wright has carved a fairly unique niche for himself in the contemporary film landscape, as the creator of original, mid-budget productions which have made him the toast of critics and fan circles, without necessarily alienating the broader mainstream audience. Just look at how Baby Driver, his fifth major movie (sixth overall, counting his little-seen DIY debut A Fistful of Fingers) is hitting cinemas in peak blockbuster season, with a marketing push to rival that of many a studio tentpole release; a show of remarkable confidence on the part of Sony/TriStar, given that the film in question is a fairly odd fish that doesn’t neatly fit into any pre-existing barrels. We can also hardly fail to note how heavily Baby Driver’s marketing his been based not so much around its cast – even though it boasts two Oscar-winners in Kevin Spacey and Jamie Foxx, as well as esteemed TV stars Jon Hamm and Jon Bernthal – but around the name of its writer-director himself. Again, a bold move, particularly as Baby Driver is in some respects quite far removed from anything Edgar Wright has done up to this point; but at the same time, his calling cards are so liberally littered across every minute of film that there’s really no mistaking it for the work of any other filmmaker working today.

Ansel Elgort is Baby, a young, fresh-faced kid with a deep love of music and remarkable proficiency behind the wheel of a car. Having suffered from tinnitus since a car crash in his youth which left him an orphan, he has long since taken to having earphones pumping music into his head on a near-constant basis to spare him the constant ringing, to the extent that he has come to rely on music to get him through certain situations – most notably when he’s working as a getaway driver for small-time crime boss Doc (Spacey). Indebted to Doc, Baby’s been working off what he owes by providing the wheels on a series of robberies, but when we meet him he’s almost paid up in full, and is looking forward to breaking away and starting a new life – potentially with his new flame Debora (Lily James). Unfortunately for Baby, it soon becomes clear that not everyone is so keen to let him leave his old life behind.

So yes, Baby Driver is a clear break from the norm for Edgar Wright in several respects. First off, we can scarcely fail to note there’s no Simon Pegg or Nick Frost (although that’s not a first, as they weren’t in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World either); secondly, it’s Wright’s first US production (Scott Pilgrim was made in Canada, even if it was largely with American money); thirdly, it’s Wright’s first solo credit as a screenwriter, having co-written the Cornetto trilogy with Simon Pegg and Scott Pilgrim with Michael Bacall (Wright also co-wrote Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin and the initial script for Marvel’s Ant-Man with Joe Cornish). Most significantly, though, Baby Driver is the first Edgar Wright movie which is not first and foremost a comedy. There’s plenty of humour in it, for sure; one scene features a gag about the Halloween movies that seems custom-designed to ensure the film doesn’t alienate the horror audience who’ve stuck by the director since Shaun of the Dead. All in all, though, this is a largely straight-faced play on the American crime thriller, intended primarily to get the adrenaline pumping. Of course, being Edgar Wright, it’s a very heightened take on that format playing with it in unusual ways, and the prominence of music is absolutely pivotal to this.

When we say that Baby Driver has a whole lot of songs in it, don’t for a moment think this is one of those movies on which they’ve just dragged out every classic rock song they could get the rights to and slapped them haphazardly on the backing track, a la Suicide Squad (note: I say that as someone who actually quite liked Suicide Squad). Every song here has been chosen very deliberately, and utilised to a very specific effect, to the point that the film often feels astonishingly close to being a musical. Think back to Shaun of the Dead’s pub battle sequence playing out to Queen’s Don’t Stop Me Now, choreographed and edited perfectly in time with the music; every key action sequence in Baby Driver plays out in much the same way. The thrash of the guitar syncs up with the screech of tyres; gunshots ring out in time with the pounding of drums. Yet once again, the aim here is not so much to prompt laughter as to draw one more intensely into the action, in a manner not too far removed from old school John Woo.

Of course, this does rather mean that’s one’s appreciation of Baby Driver may rest quite heavily on whether or not the music in question is to the viewer’s taste. For myself, having come from similar indie kid beginnings to Wright, I found it all very much my cup of tea; one particular old Blur track was a pleasant surprise, and between this and Hot Fuzz, Wright must have single-handedly boosted the sales of The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion tenfold. That having been said, I can clearly see how for some audiences the whole endeavour may reek of ostentatious muso smugness, akin to someone showing off their expansive record collection and waiting for the compliments to pour in.

By extension, another key problem may be the character of Baby himself. I think the best way I can find to describe him is if you were to put Ryan Gosling in Drive in the Fly teleporter with Billy Elliot, this is what would come out the other end. By contrast with the protagonists of Wright’s earlier films, one gets the impression that Baby is actually meant to be quite cool, but honestly, most of the time he just comes off a bit of a self-satisfied dickhead. I’m not sure how much of this is down to Wright’s script and direction, or if Ansel Elgort was miscast; while it makes sense that the role went to someone relatively unknown (I was totally unfamiliar with Elgort before now, being way too much of a grumpy old man to have watched The Fault in Our Stars or Divergent), I don’t think he really has the charisma to pull it off. Again though, this may be as much a problem with the writing, as Baby is a pretty odd character, supremely over-confident one minute, wracked with doubt the next, and as things advance he’s revealed to have a bit more of a dark side than we might first expect. Indeed, there are points when Baby Driver threatens to veer off into very grim territory indeed, yet Wright always backs off letting things get too nasty, and I’m not always sure this to the film’s benefit; it comes off a bit safe and sanitised at times. This is particularly true of the largely unsatisfying conclusion: Wright does seem to have a bit of a problem ending his films. Not an Eli Roth-sized problem, but a problem nonetheless.

Nor does Baby’s whirlwind romance with Lily James’ Debora ever really convince. Another problem of Wright’s, which he’s openly admitted in the past, is that he really isn’t great at writing female parts, and James generally has little to do but stand simpering at the sidelines, leaving us wondering why she’s willing to go so far for a virtual stranger. A shame, as beyond this the supporting cast is excellent all around, with wonderfully menacing turns from Foxx, Spacey, Hamm and a sadly underutilised Bernthal, whilst Eiza González seems to be having fun in the bad girl role. However, a particular shout-out has to go to CJ Jones as Baby’s deaf foster parent, who gives easily the most touching performance in the film entirely via sign language.

Nor does Baby’s whirlwind romance with Lily James’ Debora ever really convince. Another problem of Wright’s, which he’s openly admitted in the past, is that he really isn’t great at writing female parts, and James generally has little to do but stand simpering at the sidelines, leaving us wondering why she’s willing to go so far for a virtual stranger. A shame, as beyond this the supporting cast is excellent all around, with wonderfully menacing turns from Foxx, Spacey, Hamm and a sadly underutilised Bernthal, whilst Eiza González seems to be having fun in the bad girl role. However, a particular shout-out has to go to CJ Jones as Baby’s deaf foster parent, who gives easily the most touching performance in the film entirely via sign language.

At this point, I doubt that Baby Driver will ever be held up as Edgar Wright’s finest work; but that having been said, I remember feeling much the same way immediately after seeing Hot Fuzz, which I’ve wound up revisiting even more frequently than Shaun of the Dead in the decade since. As such, I’ve every confidence that Baby Driver will prove just as worthy of repeat viewing as everything else Wright has made thus far. Even if you don’t love it, there’s no denying it’s the heartfelt work of a filmmaker with a singular vision, and for such a film to be made in the contemporary Hollywood studio system and treated as a prestigious release is a minor triumph in itself.

Baby Driver is in cinemas now.